For this blog post I researched into Dolly Parton and the role she has played in shaping country music and challenged the ideas of the poor white hillbilly being the norm in this world. When one hears the word hillbilly they usually associate it with a man, which I think originates from the fact that the music industry was dominated by men at the time of country music being brought into popularity by white Southerners. So what is different about the way Parton presents herself? How does it simultaneously challenge the hillbilly stereotype and become extremely popular, leading her to become a timeless and iconic face within not just female country artists, but the entire genre?

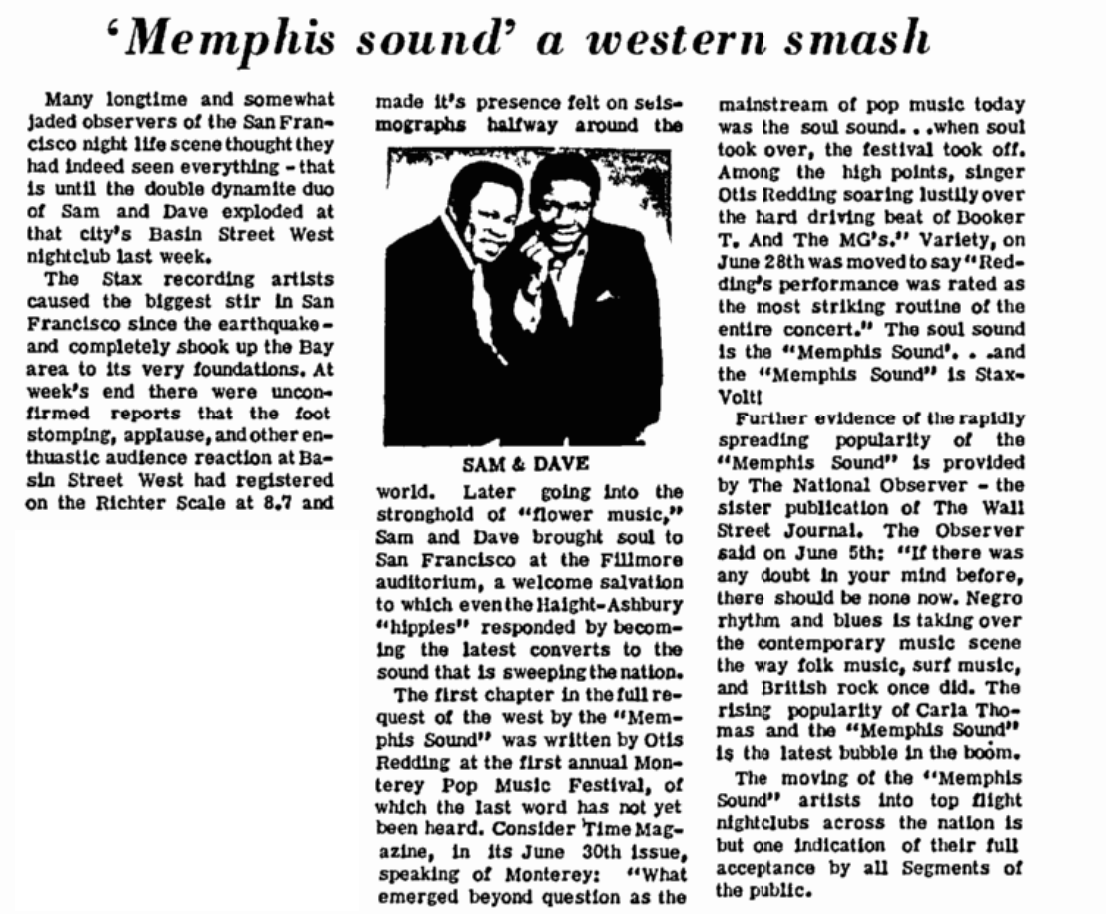

The answer lies within her music and marketing. Dolly markets herself as the common  woman, but not in the same “down on their luck” way that most people would expect country music to be presented. In her song, 9 to 5, which is also a feature film, Dolly presents us with the problems of the average person who is dealing with their dead-end job. Sure, this could be construed as someone being down on their luck, but the lyrics “They just use your mind And they never give you credit It’s enough to drive you crazy If you let it”(Parton). show this is a problem that is relatable to any listener that isn’t part of the upper 1%. The imagery of the poster shows how the working class, particularly women, are ready to take back the power from the wealthy (Gibert). This power-dynamic shift is again showing how Parton likes to fight against the typical country music narrative.

woman, but not in the same “down on their luck” way that most people would expect country music to be presented. In her song, 9 to 5, which is also a feature film, Dolly presents us with the problems of the average person who is dealing with their dead-end job. Sure, this could be construed as someone being down on their luck, but the lyrics “They just use your mind And they never give you credit It’s enough to drive you crazy If you let it”(Parton). show this is a problem that is relatable to any listener that isn’t part of the upper 1%. The imagery of the poster shows how the working class, particularly women, are ready to take back the power from the wealthy (Gibert). This power-dynamic shift is again showing how Parton likes to fight against the typical country music narrative.

This specific line is a bit hypocritical, as country music rarely recognizes the fact that much of their origins come from African American music. Still, the spirit of the song, especially sung by a woman in 1980, is that of resistance. Is it reaching to black women and saying “I”m here! I’m your ally! We’re in this together”? Well, no. It is lacking in connecting that boldly and directly, much like most country music of that era. She presents an air of sticking to your roots but not being afraid to succeed, but isn’t showing off talented African American country and bluegrass singers alongside her.

Although she isn’t making that extra step, I feel she is still stepping out and fighting the patriarchal stereotypes of country music more than other female country singers of the era. She is known for performing alongside modern feminist folk singers, like Brandi Carlile, a known gay Grammy winner. She performed the song Just because I’m a Woman with Carlile’s band at the Newport Folk Festival in 2019 (Ballantyne). This shows that she is still pushing back against double standards that oppress women, while still staying true to the historical descriptions of bluegrass and country, as the lyrics do make it feel like a complaining song, just complaints that are more relevant and valid than some more patriarchal country songs.

Works Cited

Ballantyne, Anna, director. Dolly Parton Sings ‘Just Because I’m a Woman’ with Brandi Carlile and the Highwomen at Newport Folk. YouTube, YouTube, 28 July 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=DqX4SNMpfpE.

Gilbert, Bruce, producer. “9 to 5”. Poster. Twentieth Century Fox, 1980. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs. Web. 22 Sept, 2019. [http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ppmsca.05922]

Parton, Dolly, director. Dolly Parton- 9 to 5 (Official Video). YouTube, YouTube, 15 Mar. 2014, www.youtube.com/watch?v=UbxUSsFXYo4.

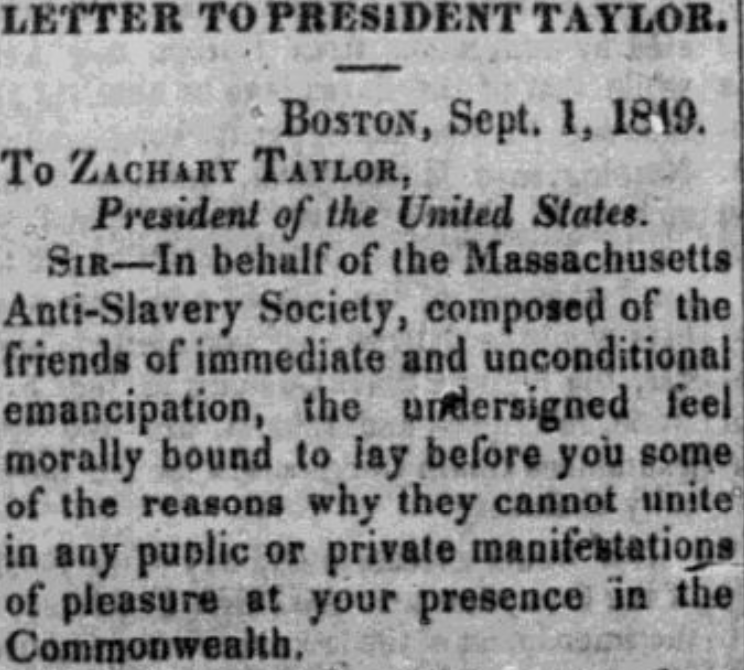

[2]

[2] [3]

[3]

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-6472881-1420086029-1218.jpeg.jpg)

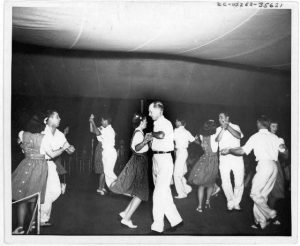

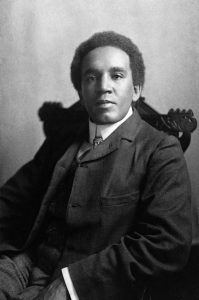

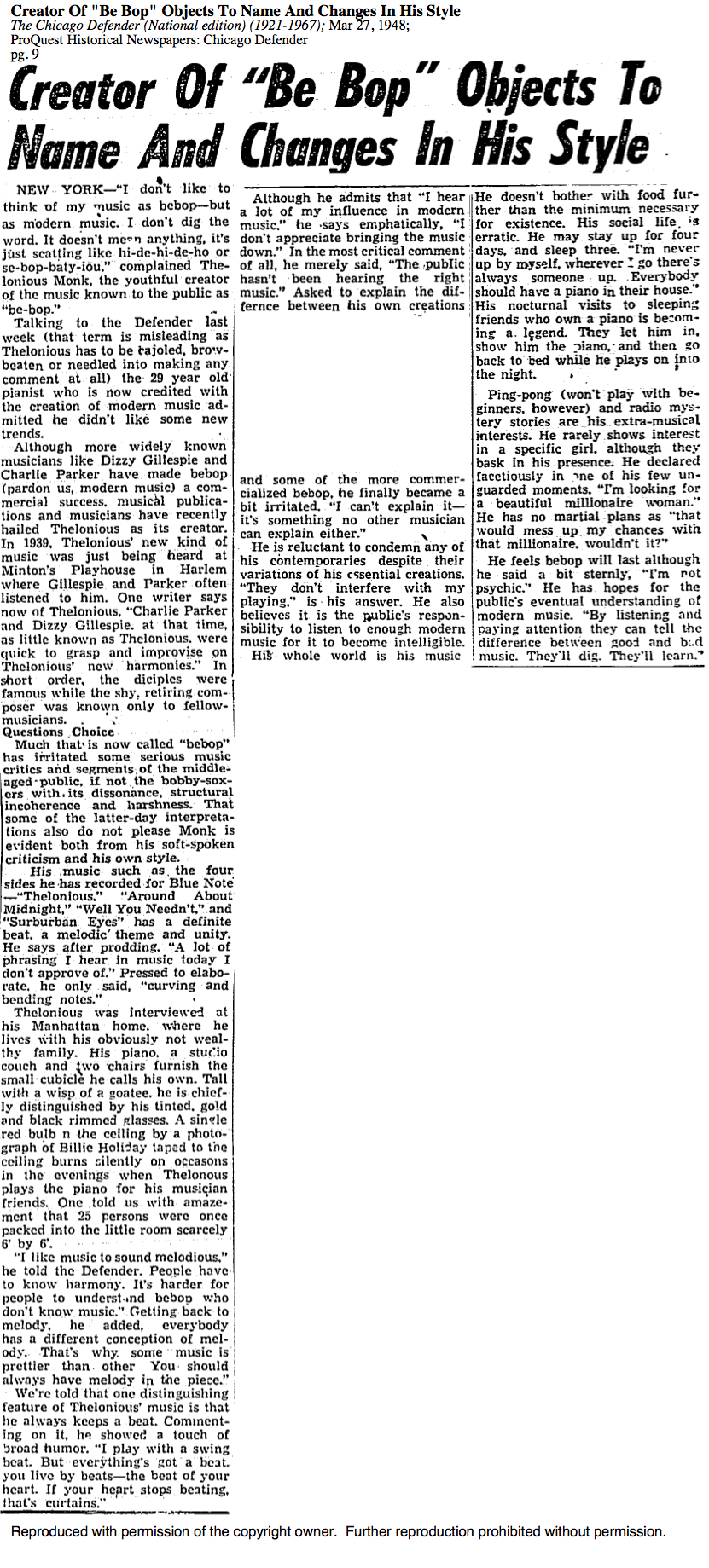

“Cafe Society,” a unique nightclub in New York City from 1938 to 1948, was always known as progressive and innovative. Deemed “the wrong place for the right people,” the club was an open place where black and white Americans could meet, mingle and socialize. The founder, Barney Josephson, sought to not only create the first racially integrated night club, but to hire and showcase primarily African American talents, including famous jazz musician Billie Holiday. While Josephson undeniably contributed to a broader interracial environment, some of the decisions he made, particularly in regards to Billie Holiday’s set, fostered an environment for “white guilt.”

“Cafe Society,” a unique nightclub in New York City from 1938 to 1948, was always known as progressive and innovative. Deemed “the wrong place for the right people,” the club was an open place where black and white Americans could meet, mingle and socialize. The founder, Barney Josephson, sought to not only create the first racially integrated night club, but to hire and showcase primarily African American talents, including famous jazz musician Billie Holiday. While Josephson undeniably contributed to a broader interracial environment, some of the decisions he made, particularly in regards to Billie Holiday’s set, fostered an environment for “white guilt.”

The March of Time series on the whole appeared quite groundbreaking in the 30’s through 50’s, when it ran. The mini documentaries of March of Time tackled some uncomfortable topics like

The March of Time series on the whole appeared quite groundbreaking in the 30’s through 50’s, when it ran. The mini documentaries of March of Time tackled some uncomfortable topics like

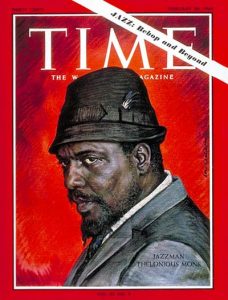

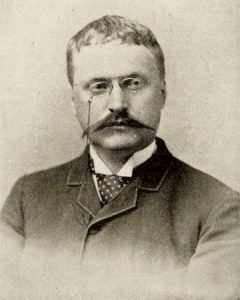

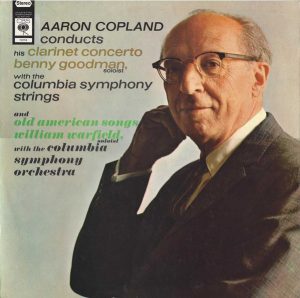

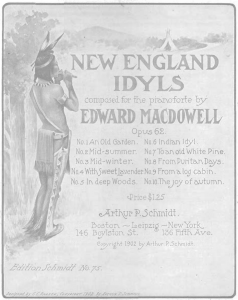

es defined by a diverse and hazy collection of backgrounds and identities. Even artists practicing extended techniques, such as Henry Cowell, relied on East Asian influences amidst his tone clusters and “vanishing chords.”

es defined by a diverse and hazy collection of backgrounds and identities. Even artists practicing extended techniques, such as Henry Cowell, relied on East Asian influences amidst his tone clusters and “vanishing chords.”

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-1600746-1240680184.jpeg.jpg)

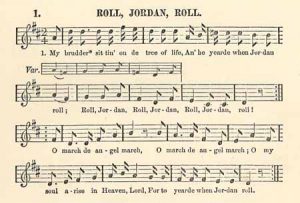

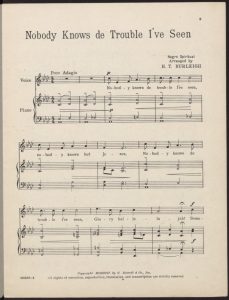

by William Arms Fisher of Anton Dvořák’s New World Symphony (No. 9, mvt II Largo, specifically). Personally, I love the symphony and have enjoyed listening to it for many years, but I can’t help but wonder now about the complicated philosophies of Dvořák and this adaptation of his work which place the work not just as a well-known music history class example to memorize, but a work that has juxtaposed good intention with possible misguided ideology.

by William Arms Fisher of Anton Dvořák’s New World Symphony (No. 9, mvt II Largo, specifically). Personally, I love the symphony and have enjoyed listening to it for many years, but I can’t help but wonder now about the complicated philosophies of Dvořák and this adaptation of his work which place the work not just as a well-known music history class example to memorize, but a work that has juxtaposed good intention with possible misguided ideology.

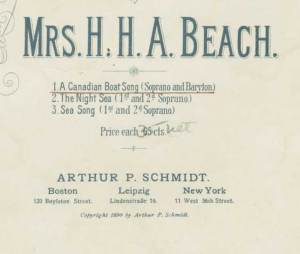

In September 2017, the New York Times honored Amy Beach’s 150th birthday with an article on her life and works. The biggest takeaway I found in this article was that her “Gaelic” Symphony shot her to compositional fame, but no orchestras have programmed hersymphony or any of her orchestral works for this season. While Beach experienced sexism at the height of her career, it is clear that sexism in classical music is still alive and well when none of our major orchestras will honor her works on this anniversary.

In September 2017, the New York Times honored Amy Beach’s 150th birthday with an article on her life and works. The biggest takeaway I found in this article was that her “Gaelic” Symphony shot her to compositional fame, but no orchestras have programmed hersymphony or any of her orchestral works for this season. While Beach experienced sexism at the height of her career, it is clear that sexism in classical music is still alive and well when none of our major orchestras will honor her works on this anniversary.

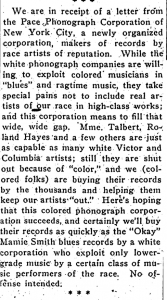

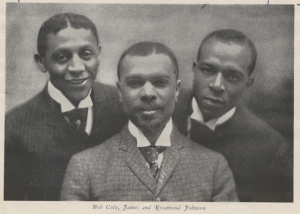

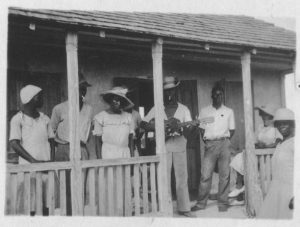

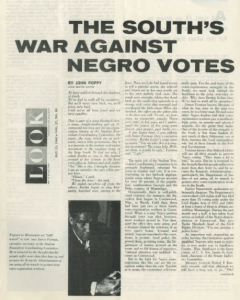

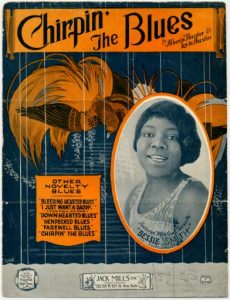

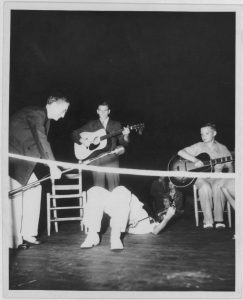

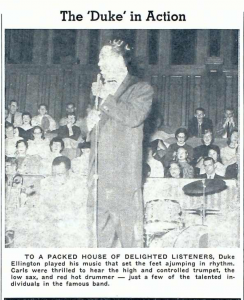

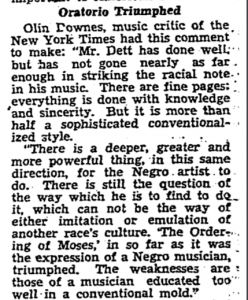

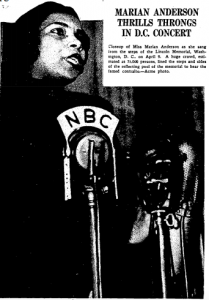

Image Courtesy of The Chicago Defender May 1937 Issue

Image Courtesy of The Chicago Defender May 1937 Issue

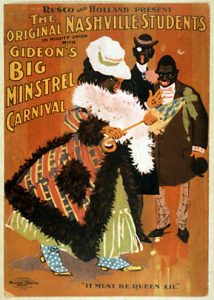

Eventually, Sherman Dudley’s circuit of theaters for African American performers, the “Consolidated Circuit,” merged into the Theater Owners Bookers Association (TOBA)

Eventually, Sherman Dudley’s circuit of theaters for African American performers, the “Consolidated Circuit,” merged into the Theater Owners Bookers Association (TOBA)