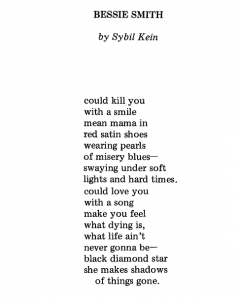

Controversy

First, a short history of Porgy and Bess.

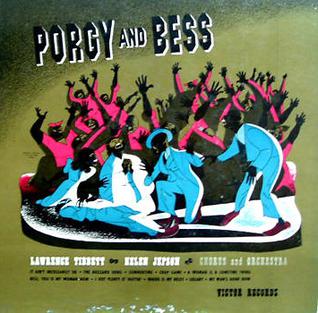

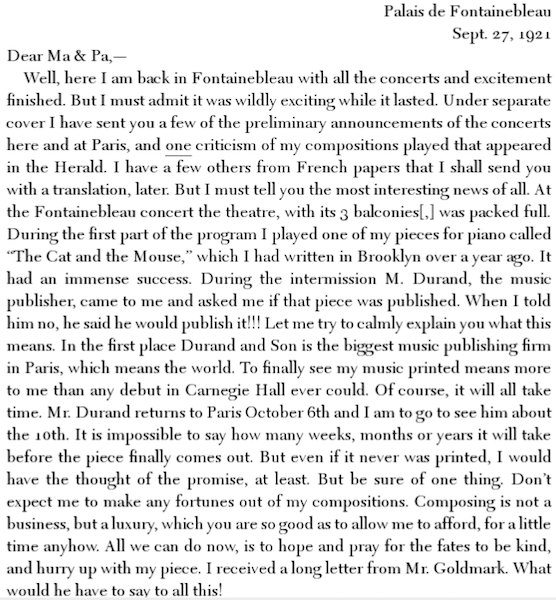

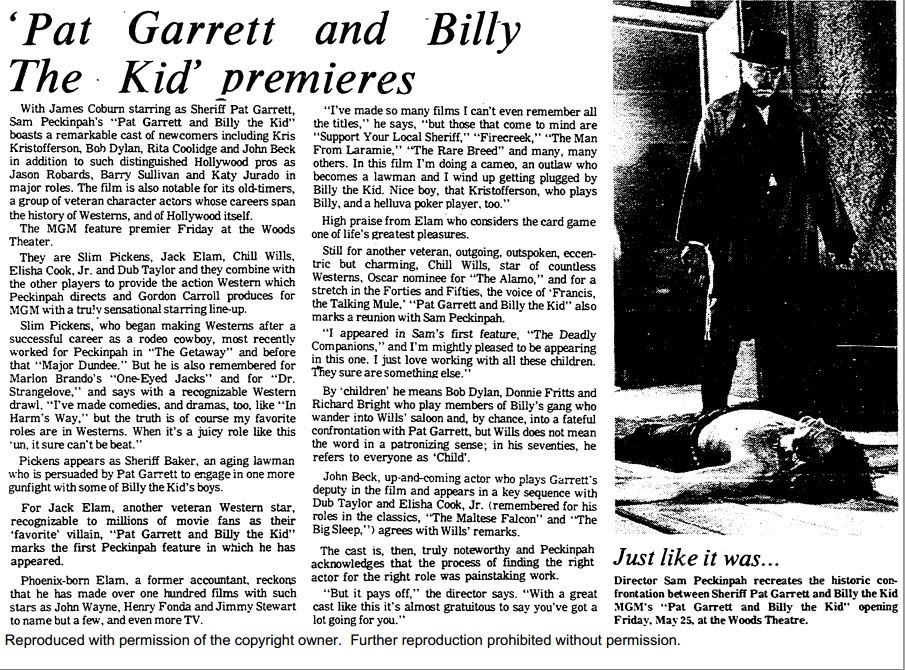

The original “Highlights from Porgy and Bess” album, featuring cover art entirely at odds with the featured vocalists, white Met Opera stars Lawrence Tibbett and Helen Jepson.

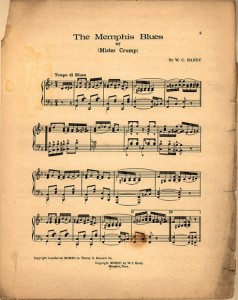

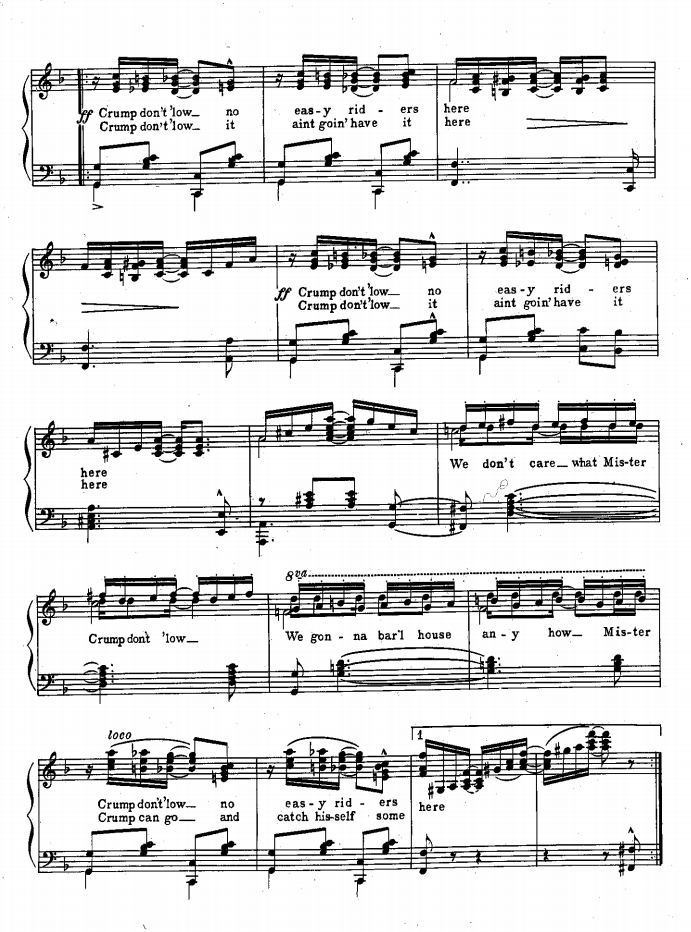

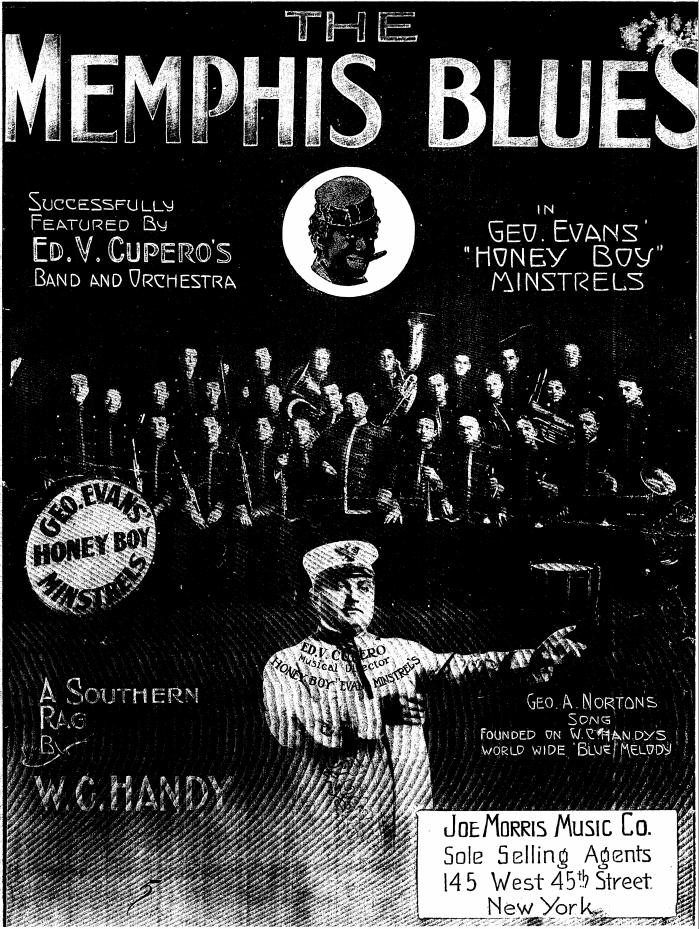

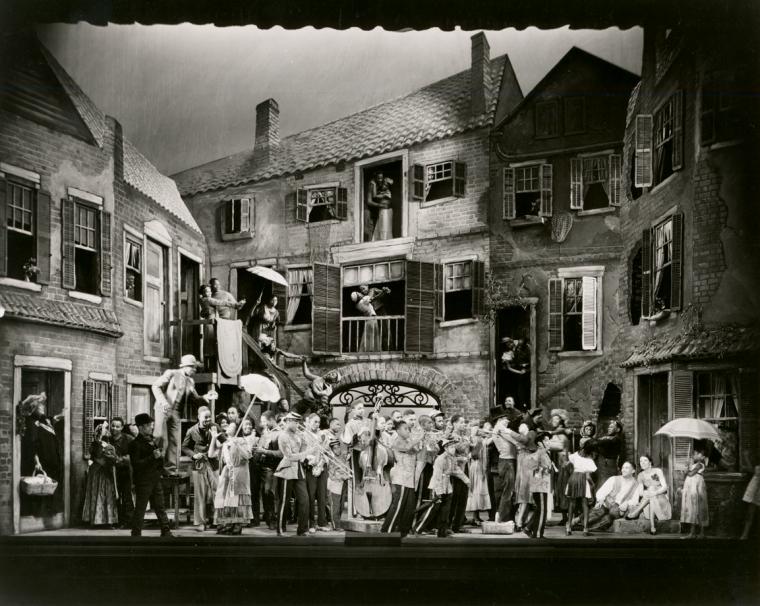

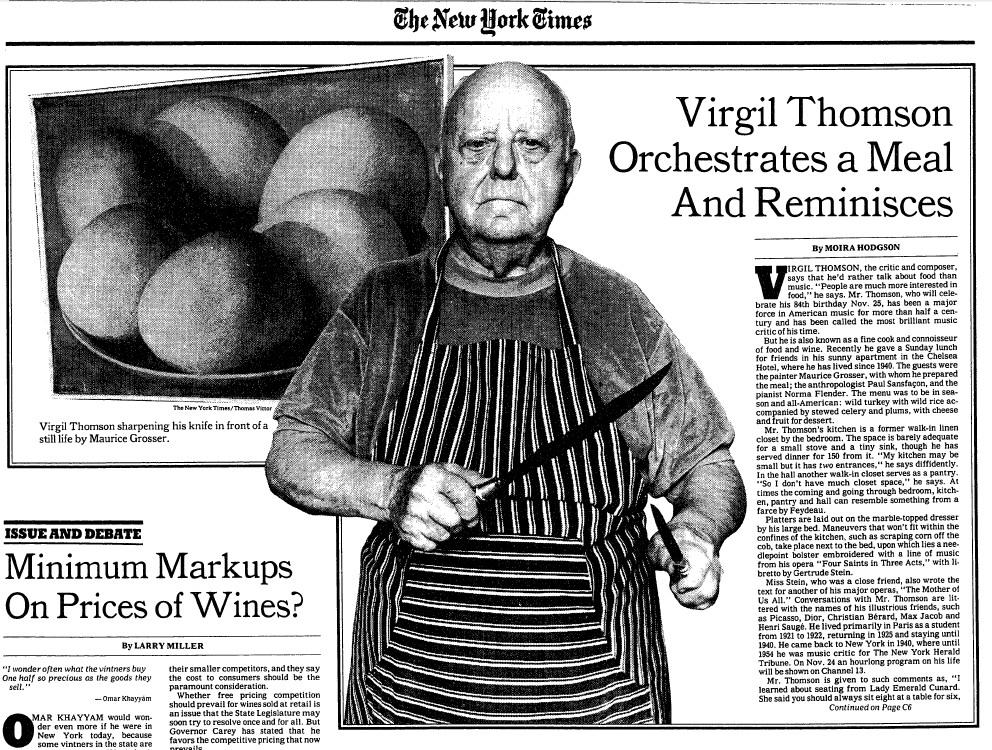

In fall 1935, the galleries of Carnegie Hall rang for over four hours (including two intermissions) with the music of George Gershwin and the lyrics of DuBose Heyward and Ira Gershwin. The private concert performance was of a new project, a grand experiment combining jazz, blues, spirituals, arias, and recitatives in a work that Gershwin described as a “folk opera,” Porgy and Bess, based on the novel Porgy by Heyward. The show became problematic for many reasons: though technically an opera featuring trained opera singers, it played according to Broadway’s schedule; the composer Gershwin had never written anything of such magnitude; while the production featured an all-black cast telling an African-American story, the author/librettist Heyward was white; the entire production crew from the director down to the stagehands to the violinists in the pit was white. In fact, the “official cast album” was recorded just days after the opera’s Broadway opening. It featured not the show’s original African-American leads, Todd Duncan and Anne Brown, as the titular Porgy and Bess, but white Metropolitan Opera stars Lawrence Tibbett and Helen Jepson, who sat in on the last few rehearsals before opening night to learn the music. Producers felt the album would be more palatable to wide audiences and therefore sell better. (Sidebar: black performers were not allowed at the Met. Duncan and Brown did finally collaborate on a Porgy and Bess album in 1940/42.)

The original Catfish Row as seen at Broadway’s Alvin Theatre (now the Neil Simon Theatre) in 1935. Photo from the Billy Rose Theatre Collection at the New York Public Library Digital Gallery.

Controversy continued to surround the show: the performers protested the racial segregation at their Washington, D.C., venue, the National Theatre. Thanks especially to the efforts of Todd Duncan (Porgy), Porgy and Bess played to the National Theatre’s first integrated audience. Many more stories could be told.

Let’s fast-forward a decade to 1943, when Warner Brothers was hard at work on their fictionalized biopic of George Gershwin, Rhapsody in Blue. Like most biopics, the storyline stretched the truth, creating two fictional romances for George, and served more as an homage to Gershwin than an accurate portrayal of his life, allowing the opportunity for full performances of Rhapsody in Blue, Concerto in F, “I Got Rhythm,” “Swanee,” and many more Gershwin hits.

Slow Progress

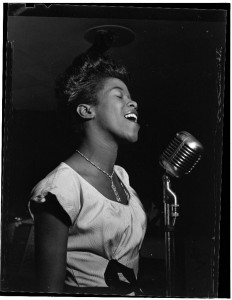

One of those other hits was “Summertime.” Judging by producers’ earlier resistance to recording an African-American Bess, one might expect the producers to opt again for a white star. But they did not ask Helen Jepson to sing. They called in Anne Brown, the original Bess, to reprise her role.

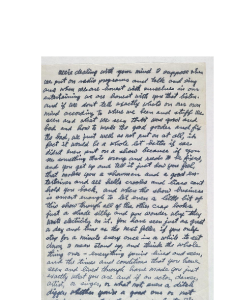

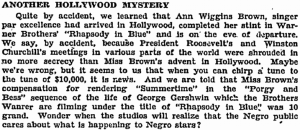

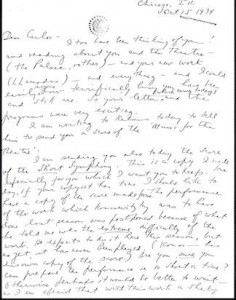

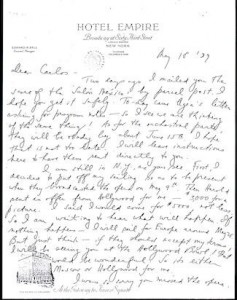

But progress seems to be a slow journey. As Alyce Key relates in an article for the Los Angeles Tribune in 1943 (this third incarnation of the paper was an African-American paper started by Almena Lomax praised for its fearless reporting), Miss Brown’s appearance in Hollywood was “shrouded in . . . more secrecy” than the WWII meetings of FDR and Churchill in Tehran, Potsdam, and Yalta:

Alyce Key’s article from the Los Angeles Tribune, September 6, 1943.

Fun fact: according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, $10,000 in 1943 is equal to $135,677.46 for one song. For comparison, Jennifer Lawrence got $500,000 for starring in The Hunger Games. The whole movie. $10,000 in 1943 was–and is–a lot of money for 3:40 of screen time.

As Alyce Key points out, people care. Gershwin cared enough to spend almost a decade working on Porgy and Bess. Todd Duncan cared enough to protest segregation at the National Theatre. The producers of Rhapsody in Blue cared enough to give Anne Brown a generous salary, but not enough to announce her involvement.

Progress, but slow progress. Maybe we just don’t care enough.

Hop on over to YouTube to check out Anne Brown’s reenacted performance of “Summertime”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WxGMWfC7tm8.

“Key Notes by Alyce Key.” Los Angeles Tribune, Sep 6, 1943. America’s Historical Newspapers, SQN: 12A55C9DAF0E8A10.

Schwartz, Charles. Gershwin: His Life and Music. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1973.

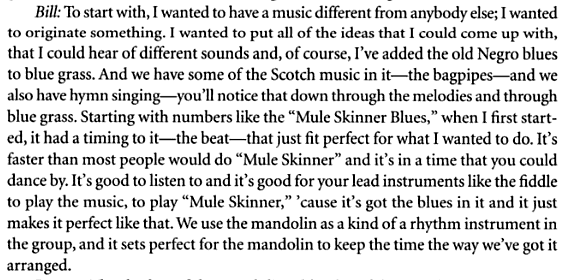

Ewing, Tom, ed. The Bill Monroe Reader. University of Illinois Press, 2000.

Ewing, Tom, ed. The Bill Monroe Reader. University of Illinois Press, 2000. Keil, Charles. “Who Needs” The Folk”?.” Journal of the Folklore Institute(1978): 263-265.

Keil, Charles. “Who Needs” The Folk”?.” Journal of the Folklore Institute(1978): 263-265.

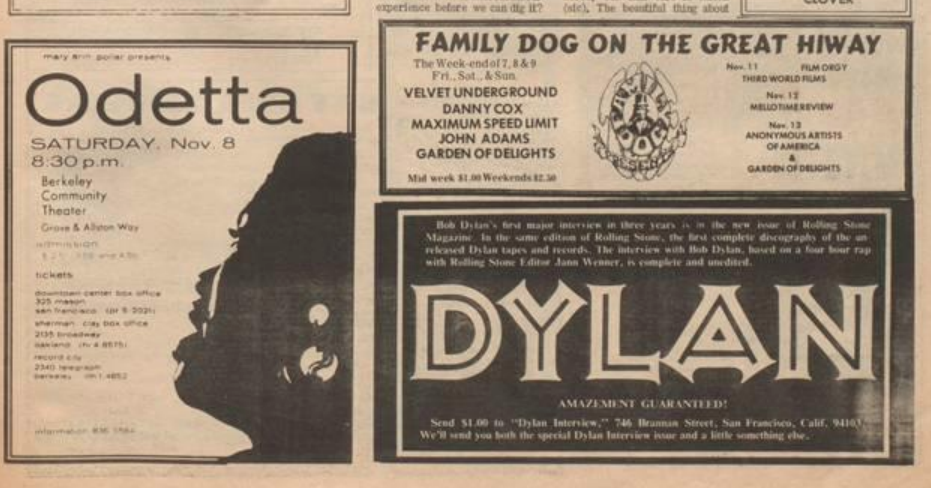

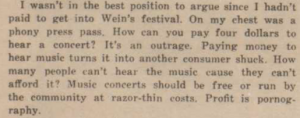

“Music concerts should be free,” he says. “Profit is pornography.” Rubin then gets himself kicked out of the festival by passing out “a copy of the free Yippie newspaper…(spiritual thoughts from our anarchist-revolutionary point of view)” to a pair of nuns. The magazines are deemed to have pornographic images themselves, and the festival cops escort Rubin out, Rubin blaming it on his hippie appearance.

“Music concerts should be free,” he says. “Profit is pornography.” Rubin then gets himself kicked out of the festival by passing out “a copy of the free Yippie newspaper…(spiritual thoughts from our anarchist-revolutionary point of view)” to a pair of nuns. The magazines are deemed to have pornographic images themselves, and the festival cops escort Rubin out, Rubin blaming it on his hippie appearance.

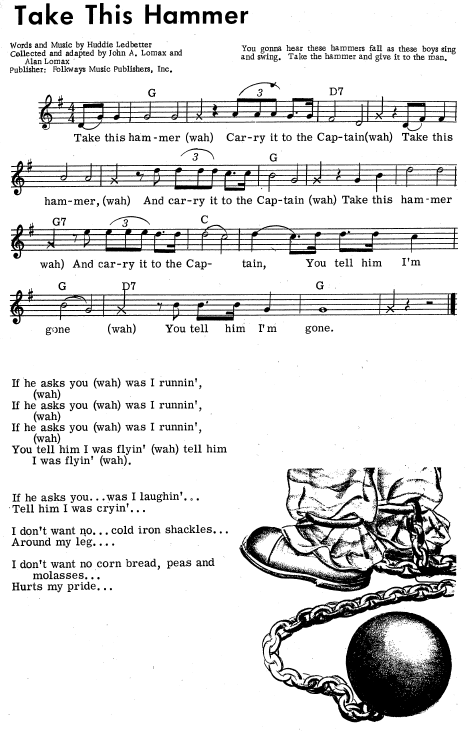

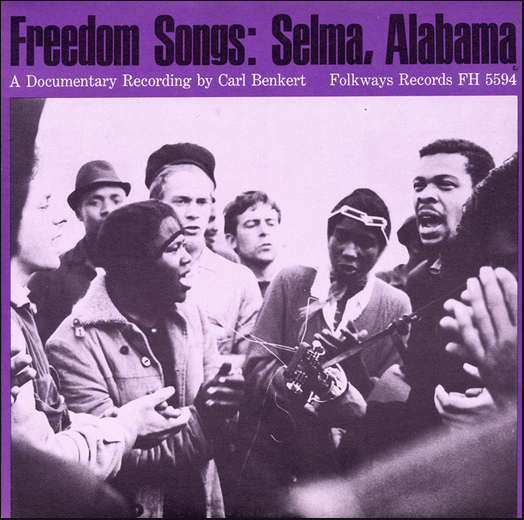

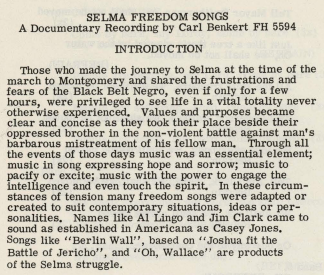

unique collection of recordings in their Smithsonian Folkways collection called “Freedom Songs: Selma, Alabama” which capture the emotional content of the march. Referred to as a “Documentary Recording,” Carl Benkert set out to preserve this moment in our nation’s history through sound. The liner notes confirm that “through all the events of those days, music was an essential element” and that the music expressed “hope and sorrow” while being able to “excite and pacify.”

unique collection of recordings in their Smithsonian Folkways collection called “Freedom Songs: Selma, Alabama” which capture the emotional content of the march. Referred to as a “Documentary Recording,” Carl Benkert set out to preserve this moment in our nation’s history through sound. The liner notes confirm that “through all the events of those days, music was an essential element” and that the music expressed “hope and sorrow” while being able to “excite and pacify.” article even specifically states that the police arrested “hymn-singing Negroes.”sup>

article even specifically states that the police arrested “hymn-singing Negroes.”sup>

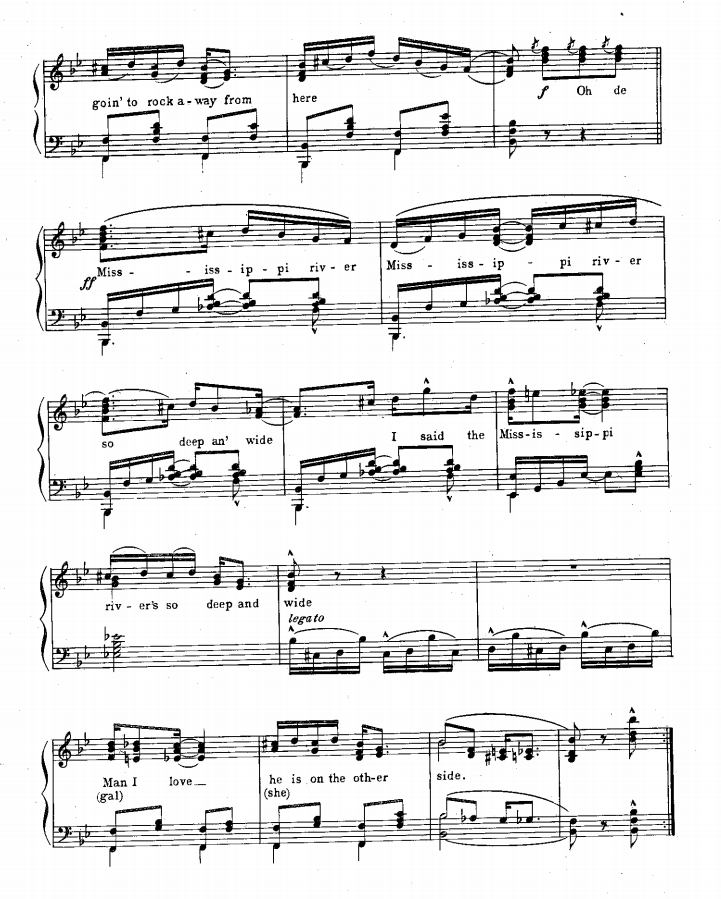

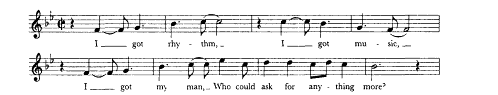

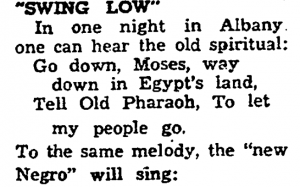

Figure 2

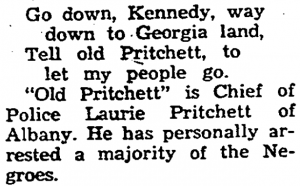

Figure 2 Figure 3

Figure 3