Black Americans have produced some of the most prolific and influential styles and genres as music, as well as some of the most influential songs. However, unfortunately for many years they were not able to receive any sort of credit or royalties from their music for many many years. The main reason they weren’t able to reach the level of fame that the white American musicians had at the time was mainly because of segregation present in the music industry, especially the recording industry. In the 1880s and beyond, musicians gained revenue from their works in two ways: through selling sheet music and through selling recordings. Black Americans were not able to access either of these things at the time.

In 1914, the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers founded in hopes of preventing copyright. Black Americans unfortunately were very poorly represented in this committee despite being the population that suffered the most from stolen and copyrighted works. Within 170 members of the committee, only 6 were black. However, another issue in printed music was people had to have experience in reading music, most of them from the time they were little, to be able to be musically literate. However, these learning experiences were often times not offered to Black Americans growing up because of the schools being segregated and the lack of music education offered. Therefore, there were many Black Americans who had an extraordinary amount of talent but were not given the privilege of music education, so despite their works being very good, weren’t able to receive profit from the printed music industry. However, there were some exceptions. A white music publisher named John Stillwell Stark created a publishing deal with Scott Joplin who was a Black American composer, known for his ragtime compositions. This publishing deal was very successful which highlights the competency of Black American musicians, as well as how sad it is that so many talented musicians were not given these opportunities.

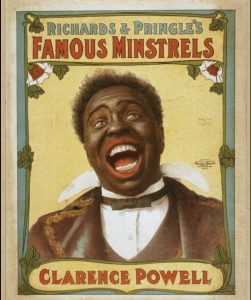

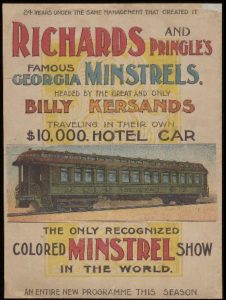

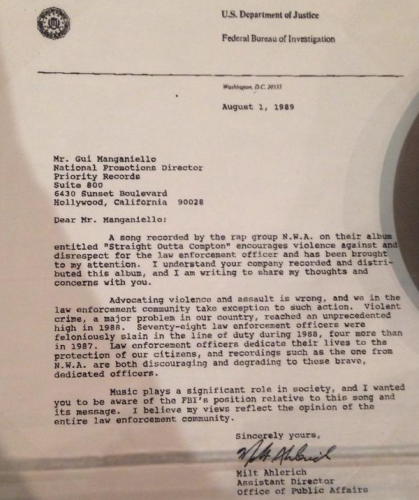

In the recording industry, very few Black American musicians were given the chance to record their songs because of bias from producers and talent agents. Although there were some exceptions, such as George Washington Johnson and Arthur Seals, many talented musicians were overlooked and not given the opportunity to gain success from their music. Instead, many white musicians stole songs written by black musicians and recorded them to gain profit. The style of blues, although created by Black Americans, was recorded on records most of the time by white musicians imitating, or appropriating the style. There were so many talented Black Americans who did not get any recognition, while many white people did. One example of this is Elvis Presley. Although Elvis Presley is extremely talented and good at what he does, a lot of his success he attained while getting ideas from talented black musicians, who didn’t receive even a quarter of the success that he did. Therefore many Black Americans were overlooked while Elvis Presley became one of the most famous rock musicians of all time.

This highlights the lack of rights Black Americans had and is very sad. It also highlights the work that still must be done to give Black Americans equal rights and an equal chance at success. As Americans, we must do better to create a safer and more equal future for those here and those to come.

https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315472096-14/industrializing-african-american-popular-music-reebee-garofalo?context=ubx&refId=1f34259a-ab47-4287-8930-894d87ce57cb

Maultsby, Portia K., and Mellonee V. (Mellonee Victoria) Burnim, editors. Issues in African American Music : Power, Gender, Race, Representation. Routledge, 2017.