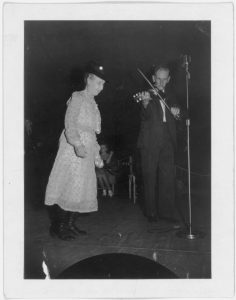

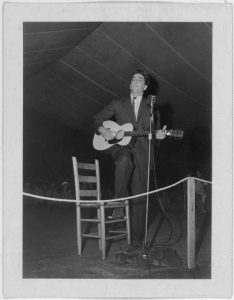

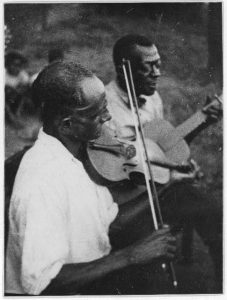

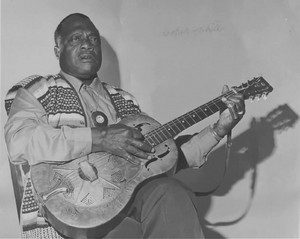

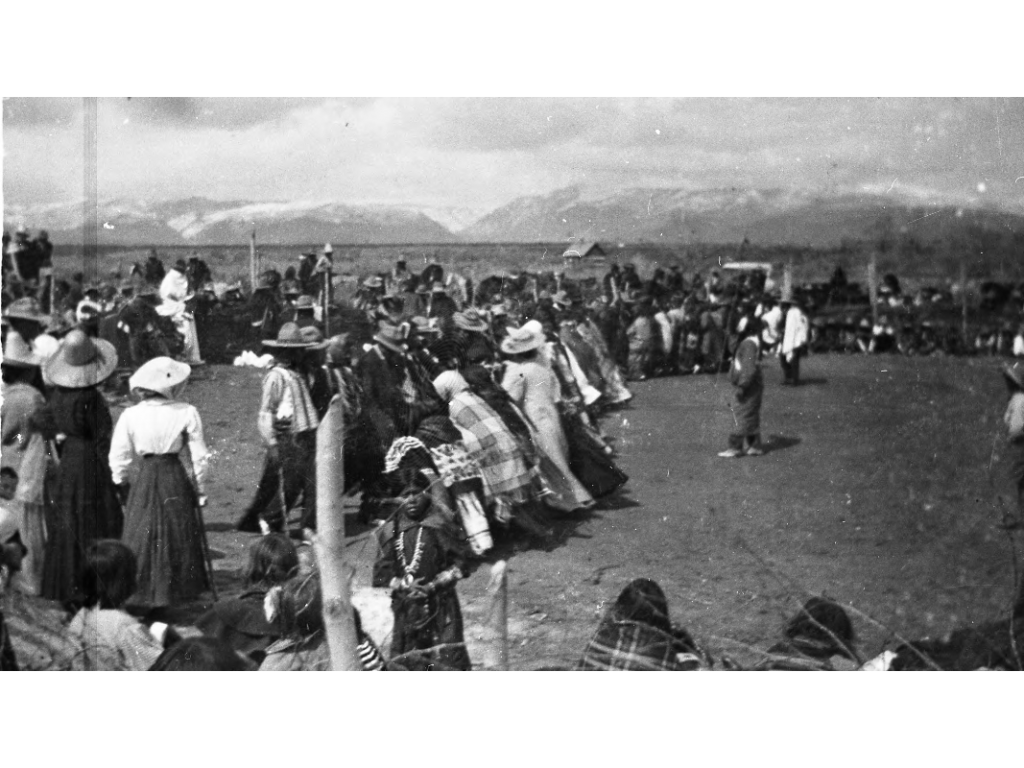

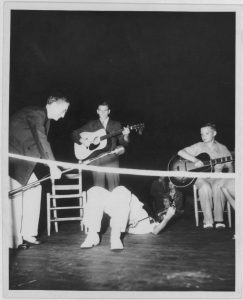

Sunny Side Boys, two youngsters, one of whom is on his back playing the fiddle, with an older man playing guitar. Bascom Lamar Lunsford is probably the man to the right of the picture holding a microphone above the fiddler. 1

This picture attempts to capture part of a tradition of country music that sums up the myth of the exclusively white origins of said genre. There is an exclusively white (male) band and given that one member can be seen playing on the floor; one that is good at what they do. Such a conception, as we have discussed in our class, seems to be largely due to the efforts of those folk song collectors and the record companies who wanted to commercialize the genre. In so doing, those scholars and companies attempted to eliminate the role of African Americans and their contributions to that style of music. So, one could say, it is not that others cannot recognize the contributions of African Americans towards the culture, it is the fact that record companies would make things “more white” to make more money that was the foundation for this erasure. This process was explicitly outlined in the writings of Erich Nunn we did for class. 2

BITHCERSHowever, what I found out while doing my research for this post is that the roots of this musical tradition can be traced back to the the US Civil War and the songs of the Confederate South. The two themes are prominent within it: a denial of black experience in the American South and this rural lifestyle as an idyllic lifestyle that is lost anywhere else.

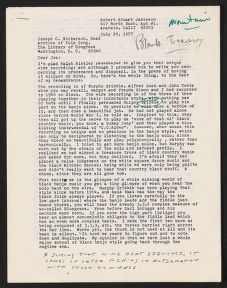

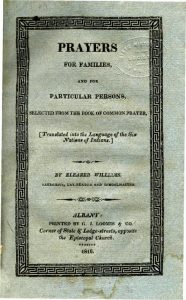

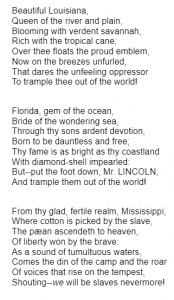

War Songs of the South Edited by “Bohemian” 3

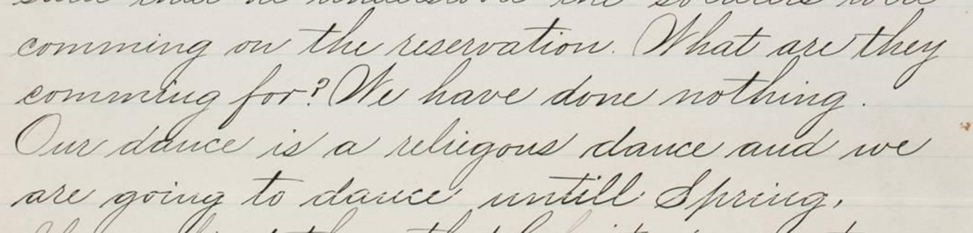

This song is only one example of many in a book of war songs but each follows this theme of a lost ideal society that was being faced with tyranny from the North. This song explicitly mentions slavery but alongside the beautiful natural conception of the South, ignoring the lives of a majority of people in that society! That idealization of the South implicitly glosses over major problems in that society.

If we understand the war songs of the Confederate South as such, It makes sense that they were the foundation for a future of denying African Americans a role in the creation of country music. The song above is one example of a history of erasing black contributions to the society they find themselves in.

Such an understanding of the pre-war South set the stage for the future conception of a rural lifestyle idealized even today in country music.Songs today in the genre revolve around the same ideas like trucks and tractors and lost love. Although in our time not explicitly negating the experience of African Americans in that rural lifestyle, it is built on a tradition in the genre of idealizing a lifestyle while simultaneously ignoring different lifestyles of many people within it.

1 Lomax, Alan. Sunny Side Boys, two youngsters, one of whom is on his back playing the fiddle, with an older man playing guitar. Bascom Lamar Lunsford is probably the man to the right of the picture holding a microphone above the fiddler. Between 1938 and 1950. Lomax Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/lomax/item/2007660175/

2 Nunn, Erich. “COUNTRY MUSIC AND THE SOULS OF WHITE FOLK.” Criticism 51, no. 4 (2009): 623-49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23131534.

3 . “Lines to the Tyrant”. Page 30-34. In War Songs of the South. Edited by “Bohemian,” Correspondent Richmond Dispatch. Richmond:West & Johnston, 145 Main Street.1862.

3154 Conf. (Rare Book Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) http://docsouth.unc.edu/imls/shepperson/shepperson.html#bohem22