When we discussed the song “Casey Jones” in class, I had only known it as a Grateful Dead song about a railroad accident, one I assumed was fictional. However, I soon came to find that it was a very real event, and that Casey Jones was a real railroader who became a folk legend after his passing.

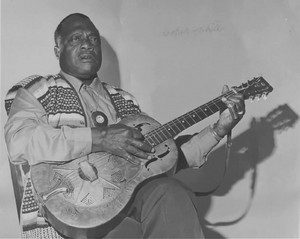

I found a recording of Casey Jones from the Library of Congress’s National Jukebox. It was recorded by Riley Puckett singing and playing guitar. Riley Puckett was a blind guitarist and singer who operated largely out of Atlanta, and was fairly popular. His rendition of Casey Jones, like most covers, stray from the original lyrics of the song. His cover tells less of the actual rail incident, choosing rather to focus more on the events after the crash than the events preceding the crash and the crash itself. Truthfully, I found it quite hard to actually make out the lyrics, but I could tell they were different than the published song lyrics by T. Lawrence Seibert, who is the accredited lyricist on the Library of Congress website.

The Ballad of Casey Jones became an extremely popular folk tune after the crash itself. Joe Hill, a famous union activist and martyr wrote a parody of Casey Jones, making him out to be a scabber who died scabbing, scabbed in heaven, and got thrown into hell by the angel unions. Funny stuff! However, the real Casey Jones was a member of two unions, the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers, according to the Water Valley Casey Jones Museum.

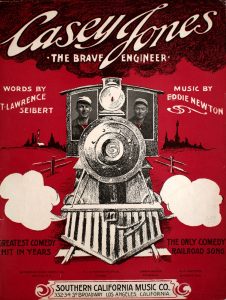

When looking at this song, one has to think about why a song becomes a folk song. In this case, it was at least copyrighted and offered for sale as a “Comedy Railroad Song”, which suggests that the intent of at least Seibert and Newton was to entertain for profit. The published version includes a verse suggesting Mrs. Jones’ lack of faithfulness to her husband, but I’ve rarely heard this verse performed, and it isn’t performed in Puckett’s recording. The original intent of the song was likely to respect and preserve Casey’s memory.

“057.048 – Casey Jones. The Brave Engineer. Greatest Comedy Hit in Years. The Only Comedy Railroad Song. | Levy Music Collection.” Jhu.edu, 2024, levysheetmusic.mse.jhu.edu/collection/057/048. Accessed 15 Nov. 2024.

“Casey Jones.” The Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/jukebox-673150/.

Lomax, John A. (John Avery), et al. American Ballads and Folk Songs. Dover, 1994.

“Mrs. Casey Jones.” Archive.org, 2024, web.archive.org/web/20131105011815/www.watervalley.net/users/caseyjones/mrs~cj.htm. Accessed 15 Nov. 2024.