It is interesting that when a majority of us think of Bluegrass music, we immediately think of it being white music, from the south, and “hillbilly.” After listening to and reading the transcript from Rhiannon Giddens’ keynote address, I found that she also had the idea that there is “whiteness” in Bluegrass (specifically the banjo), although she doesn’t use the term “whiteness,” the picture that was portrayed to her was that Bluegrass originated from white people in and around the south.

An important quote from Rhiannon Giddens

“This was not the picture I was painted as a child! I grew up thinking the banjo was invented in the mountains, that string band music and square dances were a strictly white preserve and history – that while black folk were singing spirituals and playing the blues, white folk were do-si-do-ing and fiddling up a storm – and never the twain did meet – which led me to feeling like an alien in what I find out is my own cultural tradition.”1

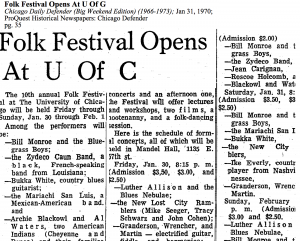

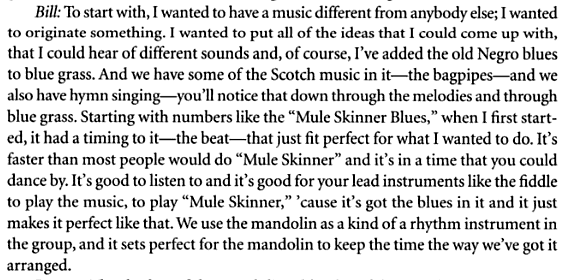

We should take note of the origins of Bluegrass. Where did it originate? Who was playing where? These are questions that most of us think we know the answer to but are in fact actually quite wrong. Bluegrass has origins that date back to as early as 1780 in Greenville, South Carolina. A majority of this music had a widespread diaspora throughout Southern Appalachia, the most notable state would be Kentucky, where the Blue Grass Boys band originated.These answers show that Bluegrass was coined by white people and that it has white origins. From listening to Giddens’ keynote address, we find these answers to be untrue.2

Another quote from Giddens

“But the black to white transmission of the banjo wasn’t confined to the blackface performance. In countless areas of the south, usually the poorer ones not organized around plantation life, working-class whites and blacks lived near each other; and, while they may have not have been marrying each other, they were quietly creating a new, common music.”1

Bluegrass music can’t be white. Although the media would say otherwise, Bluegrass music has origins from all throughout Southern Appalachia, whether it be from white people or not. White men used what they heard from African Americans and put their label on it, claiming it as their own. In other words, it’s okay when white people sing and play African American “blues” or “bluegrass” because it is entertaining but when African Americans are the ones performing, it is considered as “lazy,” used as “complaining” songs, and simply not good.3

Ewing, Tom, ed. The Bill Monroe Reader. University of Illinois Press, 2000.

Ewing, Tom, ed. The Bill Monroe Reader. University of Illinois Press, 2000. Keil, Charles. “Who Needs” The Folk”?.” Journal of the Folklore Institute(1978): 263-265.

Keil, Charles. “Who Needs” The Folk”?.” Journal of the Folklore Institute(1978): 263-265.