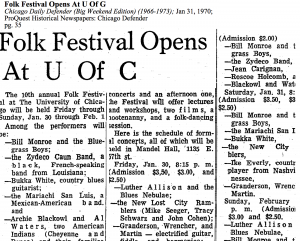

The folk revival in the United States showed a growing interest in American folk music styles and was accompanied by various folk festivals. The first newspaper article advertises a folk festival that happened in 1970. Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys are listed first, and there are other performers listed, such as blues guitarist Bukka White, a Mexican-American band, and two American Indians. With bluegrass music grouped alongside, and even above these other prominent folk music styles, it is interesting to look at bluegrass music and how and when it became recognized and categorized.

The folk revival in the United States showed a growing interest in American folk music styles and was accompanied by various folk festivals. The first newspaper article advertises a folk festival that happened in 1970. Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys are listed first, and there are other performers listed, such as blues guitarist Bukka White, a Mexican-American band, and two American Indians. With bluegrass music grouped alongside, and even above these other prominent folk music styles, it is interesting to look at bluegrass music and how and when it became recognized and categorized.

![]()

From my experiences of growing up with “folk” music, I would have assumed that bluegrass music would be at the heart of any discussion of American folk music. Most of the folk music I knew about was bluegrass, and the bluegrass music seemed to embody the meaning of folk. One article I found claims that bluegrass music is “the purest type of music in the world today.” For what reasons would this author claim that bluegrass music is the purest music? Perhaps they are the same reasons that led me to believe that bluegrass music was the most “folk” out of any other music I knew.

From my experiences of growing up with “folk” music, I would have assumed that bluegrass music would be at the heart of any discussion of American folk music. Most of the folk music I knew about was bluegrass, and the bluegrass music seemed to embody the meaning of folk. One article I found claims that bluegrass music is “the purest type of music in the world today.” For what reasons would this author claim that bluegrass music is the purest music? Perhaps they are the same reasons that led me to believe that bluegrass music was the most “folk” out of any other music I knew.

This bold claim may just be a strategic advertisement that simply reflects a desire to attract audiences, but there is no doubt that it connects to the role of bluegrass music in the folk revival. “Pure” in this context most likely means historically authentic. We have to question how “authentic” bluegrass music is. There are a few things that contradict the idea that it is purely folk music by definition. Richard Crawford notes that bluegrass music is based in the popular sphere, but looks towards the traditional sphere. Bluegrass music is defined by its old-fashioned instrumentation and older influences, such as Anglo-American folk singing and field hollers. While the connections to the past are strong, it is still a and it is known as a modern representation of Appalachian folk music with ties to popular music. Another contradiction has to do with the conception that folk music doesn’t have a clear original source. While bluegrass has many earlier influences that contributed to its existence, there is a more clear beginning with Bill Monroe and Earl Scruggs at the Grand Ole Opry. These facts don’t mean that bluegrass music isn’t folk music or that its history is too different from other folk music styles. However, I wonder what gave the writer of the second article and myself the impression that it was the purest form of music, or that it was the epitome of folk music.

This bold claim may just be a strategic advertisement that simply reflects a desire to attract audiences, but there is no doubt that it connects to the role of bluegrass music in the folk revival. “Pure” in this context most likely means historically authentic. We have to question how “authentic” bluegrass music is. There are a few things that contradict the idea that it is purely folk music by definition. Richard Crawford notes that bluegrass music is based in the popular sphere, but looks towards the traditional sphere. Bluegrass music is defined by its old-fashioned instrumentation and older influences, such as Anglo-American folk singing and field hollers. While the connections to the past are strong, it is still a and it is known as a modern representation of Appalachian folk music with ties to popular music. Another contradiction has to do with the conception that folk music doesn’t have a clear original source. While bluegrass has many earlier influences that contributed to its existence, there is a more clear beginning with Bill Monroe and Earl Scruggs at the Grand Ole Opry. These facts don’t mean that bluegrass music isn’t folk music or that its history is too different from other folk music styles. However, I wonder what gave the writer of the second article and myself the impression that it was the purest form of music, or that it was the epitome of folk music.

Sources

Crawford, Richard. America’s Musical Life. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2001.

Evans, David. “Folk Revival Music.” The Journal of American Folklore 92, no. 363 (1979): 108-15.

Haring, Lee. “The Folk Music Revival.” The Journal of American Folklore 86, no. 339 (1973): 60.

Tribe, Ivan M. Mountaineer Jamboree. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1984.

PS – Can you please add a title to your post? It makes it easier to link to. Thanks!

You’re totally right to put critical pressure on the claim that bluegrass is the “purest” folk music – “purest” is exactly the kind of hyperbolic writing that should make us skeptical. You did some great research for this post, and it was fun to see the primary sources you dug up. I would have liked to see more discussion of the “popular” nature of bluegrass; mostly you talked about its folkiness or lack thereof. What does the origins of bluegrass in the Grand Ole Opry have to do with Crawford’s designation of it as “popular” rather than “folk” music?

I’m really glad you were able to write about a topic of personal significance to you – keep up the great work!