One of the most discussed topics regarding the traditions and beliefs of other cultures and other people outside of western traditions is that of how one can attempt to understand and learn of them, without stepping into the realm of appropriation. This discussion, reflected in our class discussions on the differences between cultural sharing and cultural appropriation, is one that must be discussed, else there are consequences. As someone whose heritage lies in the Nez-Percés tribes of old in Idaho, I often question how much I can delve into the traditions without stepping on the toes of those who came before me. As someone raised in a white household, being brought up on French traditions, I do not know enough of the traditions of my ancestors, yet I have always been raised with the utmost respect for them. This respect is what leads me to crave knowledge in learning more regarding my heritage, yet it’s important to understand that I will never truly understand the traditions and beliefs of the Nez-Percés, as one cannot truly understand without being born and raised in the culture.

Cultural Misunderstandings

There are many types of cultural misunderstandings, two of which that I will discuss in this post being that of malicious cultural misunderstanding compared to ignorant cultural misunderstanding. In regards to the Nez-Percés, the first type of misunderstanding was what they encountered initially with white folk. One document I looked into was a recount written by a white man named Lawrence Kip, who was with the Escort from the 4th Infantry, regarding the 1855 Indian Council. What I focused on primarily in the recount was his descriptions of the Nez-Percés tribe before and throughout the council. In his first encounter with the Nez-Percés, he refers to it as his “first specimen” of the Nez-Percés. This initial vocabulary, in referring to the approaching tribe as the first “specimen” he encountered already places them below the white man. Without any experience with the tribe, he has already assumed them to be inferior beings to himself, and this will continue throughout his experience with the tribe, as it did in the minds of many other white men.

In continuing his description of the natives he encountered, the western world’s infatuation with the exotic was also portrayed. He described them in a majestic light, claiming that they assumed the grace of centaurs, being one with their steeds. They were “gaudily painted,” had “fantastic embellishments flaunted in the sunshine,” and had “fantastic figures” covering their bodies. In the end, he wrapped up his initial description as “wild and fantastic.” To him, they were wild savages, yet they were fascinating, fantastic, and something utterly exotic from what he’d experienced before.

The Nez-Percés were known to be one of the kindest tribes to the white men, yet while visiting one of the Nez-Percés chiefs, Kip lumped them and their enemies, the Blackfoot tribe, together as savages. The lack of distinction between two tribes, one seemingly more violent to the white men than the other, shows the lack of care and thought that the white folk gave the tribes, no matter how kind.

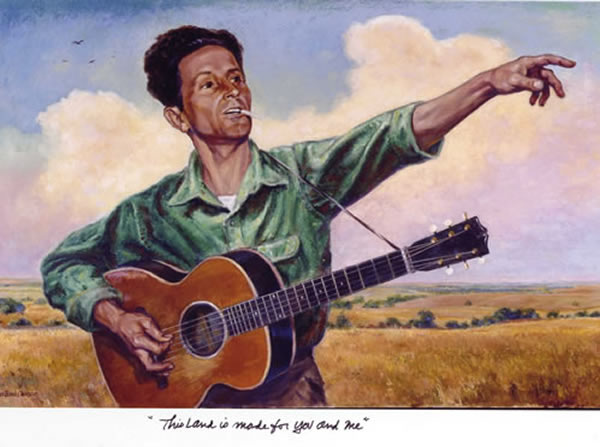

It has been greatly discussed that the musical accomplishments of native americans stray from those in western culture, although that does not in any way diminish their music. Pitches and rhythms that are not in the western music cannot be dismissed as lesser, or incorrect, but must rather be adopted, as they are all music. Kip described their musical instruments as of the “rudest kind,” their singing as “harsh,” and overall “utterly discordant.” Even one who was not adept in music couldn’t find a way to appreciate what he heard, and instead described it in the words that we don’t dare use to describe music. While something may be discordant, it is still appreciated in western culture, unless, it seems, it is a part of another culture altogether, in which case it is dismissed as something that is not music, and something we cannot appreciate in the same manner.

Kip’s description of his experience with the Nez-Percés tribe is not to be taken as a factual and perfect account, as he had his biases. It is important to search other references, as I shall continue to do so in later blog posts. This original conception of the Nez-Percés tribe was something that was later to bring on the Nez-Percés Campaign, where the white men went to war with the tribe. This misunderstanding and refusal to understand other cultures was what brought on violence, and is what I’m referring to as a malicious misunderstanding. While it was not explicitly malicious to begin with, the fact that the newcomers found the native american tribes to be inferior to them was the beginning of homicide. What could be considered a misunderstanding was not solved in an equal and understanding manner, therefore there was no resolution.

Nez-Percés Campaign

Another very interesting document that I found was a map of the Nez-Percés Campaign. It depicts the path taken by the newcomers in their war against the Nez-Percés, as well as drawings of fighting grounds, military movements, and notes of times and dates when specific events occurred. It is the prime example of the consequences that can happen from cultural misunderstanding and more specifically, the lack of respect and attempt for peace with other cultures.

Nez-Percés Traditions and Religions

The second misunderstanding I’m going to discuss occurs often in today’s world, and is something I’m experiencing currently when researching the Nez-Percés. I am aware that for all of the research I can do, I can only gain a small glimpse into the truth regarding the culture of the Nez-Percés, and I cannot hope to truly understand their culture and traditions. At the same time, in my attempts to research it I hope to gain more insight on something that is both important to me, and should be important to everyone else out there, as it is important to learn and respect other cultures.

In R. L. Packard’s “Notes on the Mythology and Religion of the Nez-Percés,” he goes into detail of first hand accounts of a very small amount of traditions of the Nez-Percés. He gets his information in a discussion with James Reubens, who is a member of the Nez-Percés tribe. Even at the beginning of the conversation, the concept of misunderstanding and lack of respect in learning as portrayed in Reubens’s statement that he was worried Packard only had the “idle curiosity of a white man,” rather than a true passion for learning and respecting Nez-Percés traditions. This statement is a prime example of the issue at hand, where people are ignorant of the cultures they are stepping on and appropriating, yet make no attempts to learn about them in depth. Sometimes, it is due to pure ignorance, as they do not know that there is an issue, but other times it is due to laziness, which is something else altogether that we must combat.

As Reuben continued to discuss Nez-Percés traditions and beliefs, he touched on another prominent barrier in true understanding. He said that “the way we (the Nez-Percés) get our names is a beautiful thing when told in our language, but I cannot tell it well in English.” The language barrier that exists is extremely inhibiting, yet unavoidable. Without knowledge of the language and time spent with the culture, one cannot hope to gain true understanding of it. At the same time, this is another reason people are unwilling to learn, and wish to simply continue living their lives in an ignorant manner.

One tradition that was extremely interesting to learn about was the tradition of how children received their names in Nez-Percés culture. I do not dare to paraphrase the process, as it is complex and deserving of a true description. Even now, I am using a paraphrasing that Packard received in his discussion with Reubens.

“When a child is ten or twelve years old, his parents send him out alone into the mountains to fast and watch for something to appear to him in a dream and give him a name. His success is regarded as an omen, and affects his future character to some extent. If he has a vision, and in the vision a name is given him, he will excel in bravery, wisdom, or skill in hunting, and the like. If not, he will probably remain a mere nobody. Not to every child [boy or girl] is it given to receive this afflatus. Only those serious-minded ones, who keep their thoughts steadfastly on the object of their mission, will succeed. The boy who is frivolous, who allows his attention to be distracted by common objects on his way to the place of vigil, or who while there succumbs to homesickness, or gives himself up to the thoughts about hunting in the woods he has passed, or fishing in the streams he has crossed, will probably fail in his undertaking. On reaching the mountaintop, the watcher makes a pile of stones three or four feet high as a monument, and sits down by it to await the revelation. After some time – it may be three or four days – he “falls asleep,” and then, if fortunate, is visited by the image of the thing which is to bestow upon him his name and the wisdom and power belonging to it.”

Why does this matter to me?

One thing in particular rang with me in reading this description, and that was the line “the watcher makes a pile of stones three or four feet high as a monument” atop the mountains. Towards the end of the section, Packard mentions that “there are many of these little monuments referred to on the mountains of Idaho.” Growing up, I often came across these monuments, as did others, but people simply believed they were put there by others hikers, and added their own stones to the piles. I did the same. Never once did it occur to me that the piles of stones were monuments to something more important, something that I should have been respecting throughout my entire childhood.

Why does this matter to anyone?

In learning about one simple tradition, I gained a deeper understanding and respect for the culture, and it is something that I will spread to all those who I am with when I run into these monuments. I believe that it is important to take the time to learn about other cultures, and it is important to learn to respect them. Objects such as the first hand accounts regarding some old white man’s first experience with the Nez-Percés tribe, albeit biased, is something that we must study in order to understand past mistakes, and in order to never make them again. Maps of conquests, while violent, are something that we must view in order to understand the occurrences and events that formed the present. First hand accounts are something that we must listen to, and something that we must always respect, especially when they are difficult to share. While we cannot truly understand, we must make an effort in order to avoid the mistakes of our predecessors and ancestors. Through research, discussion, and open-mindedness to learn, we must work to understand and respect everyone.