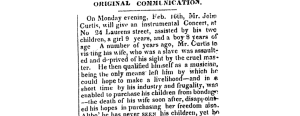

This week I found a newspaper article, listed as being released in 1829, advertising a concert to be performed in New York City. Not only does it advertise as was expected, it outlines the life story of the leading musician, a story that shed some light on the experience of a free Black man in the time of slavery who also happens to be a touring violinist accompanied by his adolescent children. They are also touring violinists.

Link to the original document: https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&t=articletype%3A10%21News%2BArticle&sort=YMD_date%3AA&fld-base-0=alltext&val-base-0=concert&val-database-0=&fld-database-0=database&fld-nav-0=YMD_date&val-nav-0=&docref=image/v2%3A132FB88A16969E1C%40EANAAA-132FC901F5179168%402389126-132FC8170D4A6B88%402-1389CBB8E38687B3%40Original%2BCommunication&firsthit=yes

The article describes the experience of Curtis from being blinding by his wife’s slaver, to purchasing his kids from bondage with money he earned performing music, to finally teaching them how to play violin as well. At first I was surprised at the sympathetic tone this article sported while telling the story, then remembered that the article is from an African American publication, one that would likely empathize quite a bit more than their white counterparts with the plight of a struggling black man.

There isn’t much to be said about John Curtis. A pointed google search of the violinist followed by the publication year and the publication’s location in New York showed me very little. As the article very concisely summarizes the artist’s life up to the point of the concert, it reveals the concert’s exact location. It’s then that I searched up Laurent street, the street where John Curtis and his two children played the violin, and found that it was once referred to as “Rotten Row”, by a less than scholarly blog from 2011.

Check it out: https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&t=articletype%3A10%21News%2BArticle&sort=YMD_date%3AA&fld-base-0=alltext&val-base-0=concert&val-database-0=&fld-database-0=database&fld-nav-0=YMD_date&val-nav-0=&docref=image/v2%3A132FB88A16969E1C%40EANAAA-132FC901F5179168%402389126-132FC8170D4A6B88%402-1389CBB8E38687B3%40Original%2BCommunication&firsthit=yes

While the source had some less than charitable things to say about the Laurent street that once was, it is very clear that John Curtis’ conditions for performance were less than ideal. Not only was he, a blind, black man in the time of slavery, a working musician. He was touring with two children, both taught in the art of the violin, both taught by a father who had never laid eyes on them. The opportunities for performance were, as we’ve studied, events for slavers and for run down concert halls in poor neighborhoods.

With all our conversations about the origins of “American Music” and defining the term for ourselves, our conversations cannot understate the importance of black music to the overall scope of American music, undefined as it may be. Performers like John Curtis, and the stories that they leave behind, will likely go unstudied and their personal stamp on the world of classical music, in particular, will likely remain undiscovered. The tragedy of music history is the lack of information available to further recognize this man’s contribution to the world of music.

(There isn’t much to say, I just wish that there was a movie about this guy)