For this blog post, I was going to focus on When Johnny Comes Marching Home Again and its Civil War origins changed for the Glenn Miller Band. I like other blog posts are striving to write for narratives that don’t just tell a story of white culture. As my final blog post, this attempts to shine light on marginalized groups and the importance of music in ties to their story.

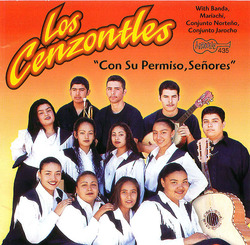

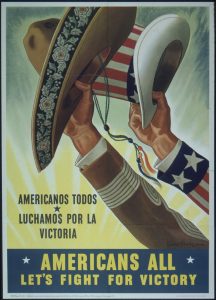

While Glenn Miller adapted the 19th century song to his style of jazz to rally national spirit against the US enemies of World War II, using jazz as a strictly white American identity, in Mexican culture, something similar happened. Pedro Infante recorded the song, El Soldado Rosa, in 1943 for Mexican soldiers fighting in World War II.

The lyrics state:

Me voy de soldado raso

Voy a ingresar a las filas

Con los valientes muchachos

Que dejan madres queridas

Que dejan novias llorando

Llorando su despedida.

Voy a la guerra contento

Ya tengo rifle y pistola

Ya volveré de sargento

Cuando se acabe la bola

Nomas una cosa pienso

Dejar a mi madre sola.

Virgen morena

Mandale su consuelo

Nunca jamas permitas

Que me la robe el cielo.

Mi linda Guadalupana

Protejela a mi bandera

Y cuando me haga en campaña

Muy lejos ya de mi tierra

Les probare que mi raza

Sabe morir…

Translation:

I am going as a buck private,

I am going to the front lines

with brave boys

who leave beloved mothers,

who leave sweethearts crying.

Crying on their farewell.

I am leaving for the war content,

I got my rifle and pistol,

I’ll return as a sergeant

when this combat is over;

The only thing I regret:

leaving my mother alone.

Brown Virgin,

send me your blessing,

never allow

heaven to steal her from me

My lovely Guadalupe

will protect my flag

and when I find myself in combat,

far away from my land,

I will prove that my race

knows how to die anywhere.

I leave early tomorrow

as the light of day shines

here goes another Mexican

who knows how to gamble his life,

that gives his farewell singing:

singing to his motherland.

Brown Virgin,

I entrust my mother;

take care of her she is so good,

take care of her while I’m away.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b-u-tWKr4AI

I find the line that discusses one having to die in war in order to p

rove their race is worthy particularly striking. In modern media, Latinx people are not depicted with respect so I cannot imagine the kind of bigotry faced during this time of national pride and lack of representation in mainstream media.

In a correspondence with former bracero Adolfo González, he states how important these pieces were to Mexicans for their morale in the war. He states:

“Ã, cÃémo no. De aquel señor Jorge Negrete que era entonces y el señor Infante, esos eran muy grandes, grandes cantantes que lo divertÃan a uno. Cantinflas. (risas) (“Of course. Jorge Negrete was popular back then and then Pedro Infante. They were popular, great singers. They would entertain us. Cantiflas. [laughter].”)

Many in Mexican culture considered Infante very popular. Many migrant workers would sing his songs including El Soldado Rosa. The content produced by record companies to support the war and music presented from the soldier’s perspective is infinite but in contemporary media, we often gloss over content of minorities (specifically Mexican) and how

the war affected the music they produced and wrote.

Bibliography:

–YouTube, YouTube, www.youtube.com/watch?v=b-u-tWKr4AI.

-““El Soldado Raso”.” The American Mosaic: The Latino American Experience, ABC-CLIO, 2019, latinoamerican2.abc-clio.com/Search/Display/1481722. Accessed 18 Nov. 2019.

-“Bracero Program: Adolfo Gonzáles (Daily Life).” The American Mosaic: The Latino American Experience, ABC-CLIO, 2019, latinoamerican2.abc-clio.com/Search/Display/1741283. Accessed 18 Nov. 2019.

[1]

[1]