The idea that a black female pop artist is “too white” is unfortunately nothing new. In a 1988 article published in Ebony magazine (a magazine written by and for an African American audience), Lynn Norment talks to Whitney Houston. Norment claims “Black disc jockeys chided her for ‘not having a having a soul,’ and ‘being too White,’ while other critics [said] she [was] ‘too distant and impersonal [1].’” I thought Houston’s response was very interesting. Houston explains:

“‘Picture this […], you wake up everyday with a magnifying glass over you. Someone is always looking for something- somebody, somewhere is speaking your name every five seconds of the day, whether it’s positive or negative. Like my friend Michael [Jackson] says, ‘you want our blood but you don’t want our pain.’ […] Don’t say I don’t have a soul or what you consider to be ‘Blackness.’ I know what my color is. I was raised in a Black community with Black people, so that has never been a thing with me. Yet, I’ve gotten flak about being a pop success, but that doesn’t mean I’m White…pop music has never been all-White. […] My success happened so quickly that when I first came out Black people felt ‘she belongs to us,’ […] and then all of a sudden the big success came and they felt I wasn’t theirs anymore, and I wasn’t within their reach. It was felt that I was making myself more accessible to Whites, but I wasn’t.’”

Whitney Houston, 1983.

This idea of not belonging seems to be a common theme among female pop singers of color. In a recent example, pop artist Lizzo has experienced the tug-of-war between being in the black community, yet appealing to largely white audiences. She is also a classically trained flautist, who often pulls out her flute during performances (between twerking), and this further complicates people’s perceptions of what “black pop music” really is.

People from the black community are releasing tweets like the following:

Another Tweet in Response:

On the “white” end of the spectrum, “white girls” are posting pictures about attending concerts and using Lizzo’s song lyrics for captions:

There are some strong opinions present here, and these social media posts are obviously not representative of entire communities, but I think it is important to see how the general public is perceiving Lizzo as an artist.

So what can I do as a listener and performer to break down these stereotypes? Is it okay for me as a white woman to attend concerts or to perform music by these black female artists? Professor Louis Epstein, of St. Olaf College, says that it is a “good idea for people who live “whiteness” to feel limited- but it also reinforces boundaries [2].” These boundaries can cause even more limitations. In class, we also discussed strategic essentialism (the idea that under pressure and in the context of oppression, minority groups draw together while ignoring differences to present a unified front),

as something that has positive intentions like protecting oppressed minorities and giving them political power. Strategic essentialism also has unintended consequences, such as reducing a people to homogeneity and potentially contributing to the very racialist logic they’re trying to overcome.

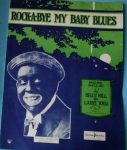

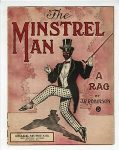

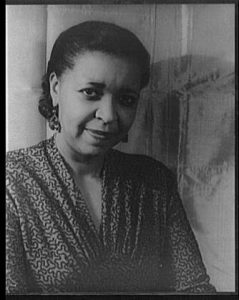

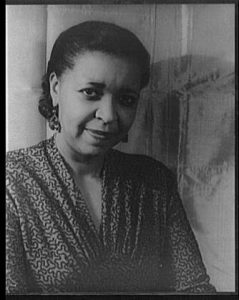

Ethel Waters, another black female singer accused of sounding “too white,” was the fifth black woman in history to record a record (she also was the first black woman to have her own television show, The Ethel Waters Show. Waters performed throughout the Harlem Renaissance, but as her fame grew she performed for primarily white audiences. picture courtesy of the Library of Congress

Rhiannon Giddens, on the subject of bluegrass, says “the question is not, how do we get diversity into bluegrass, but how do we get diversity BACK into bluegrass [3]?” This idea readily applies to pop music, and how artists are overcoming th seperations between “white pop” and “black pop.” We as audience members, listeners, and performers need to bring diversity back into pop music and make it okay to have artists included from a variety of different backgrounds. As Whitney Houston says, pop music has never been “all-White,” so the idea that we need to make subdivisions between “black pop music” and “white pop music” seems like a step in the wrong direction. Giddens explains that”we have a lot of work to do. We need to build on these moments, on these incredible opportunities [like going to a Lizzo concert] to expand understanding [3].”

I have a hard time knowing how to handle issues like this. On the one hand, I love the music that black female pop artists are releasing (because it’s honestly so incredible), on the other, I don’t want to take their life experience and claim it as my own. I think the most important thing that listeners and performers who are not part of the African-American-women’s experience is to educate ourselves. Go out and find artists of color that may not have gotten the same publicity as their white counterparts- this is especially important in music genres that are typically considered “white” music (classical, country, pop, etc.). Another way is to keep up the conversation. Talk to peers, other musicians, and people outside of your own community. This issue isn’t going to be fixed overnight, but with conversations I believe learning and understanding will take place.

Bibliography:

[1] Norment, Lynn. “Whitney Houston Talks About the Men in Her Life- and the Rumors, Lies, and Insults that are the High Price of Fame.” Ebony (1848-1921), vol. XLVI no. 7, May 1991.

[2] Epstein, Louis. Lecture to his American Music class, September 2019.

[3] Giddens, Rhiannon. “Rhiannon Giddens Keynote Address.” Paper presented at the IBMA Business Conference, Raleigh, NC, September 2017.