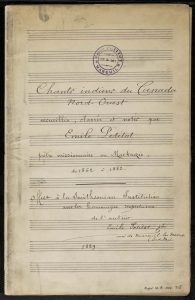

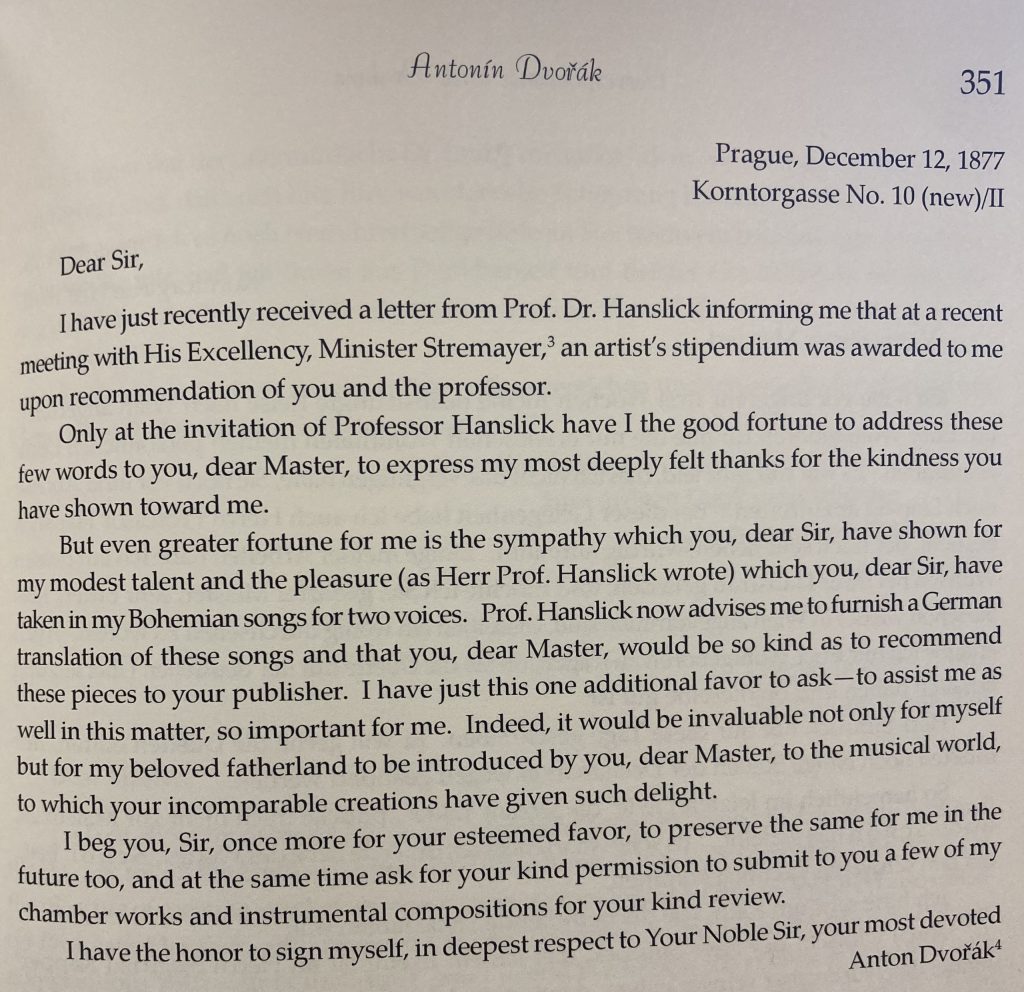

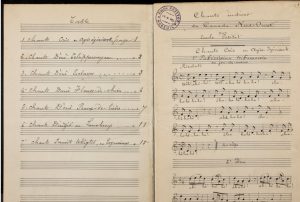

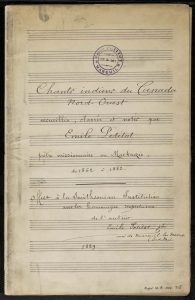

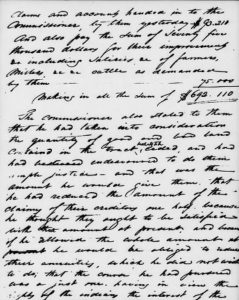

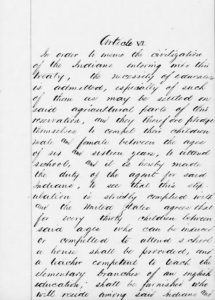

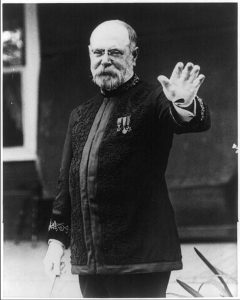

While looking for a source to spark my interest in writing this blog post, I found this manuscript seen below.[1] This manuscript was transcribed by Father Emile Petitot, a Roman Catholic Preist.[2] This sparked my thinking of common themes discussed among blog posts in the past. The idea of White Saviorism and the need to record practices from cultures other than your own. Petitot encountered various indigenous tribes in the land we now consider Canada. During these years of contact, he served as a missionary priest to the indigenous tribes. After these encounters, Petitot was convinced that liquor and guns were threatening indigenous culture and began to fervently record their cultural practices. That is how the ‘Chants indiens du Canada Nord-Ouest’ was created, the document you see below.

Cover of Chants indiens du Canada Nord-Ouest by Father Emile Petitot

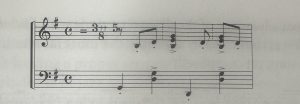

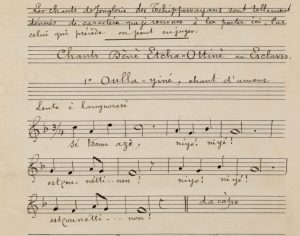

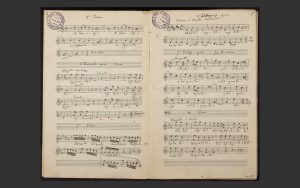

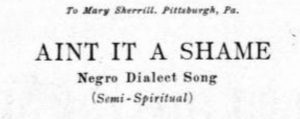

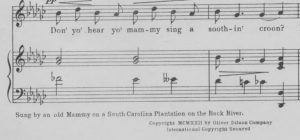

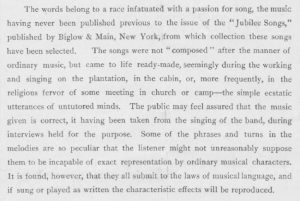

There are a couple of different things wrong with this document. Most notably, we see once again the attempt to transcribe indigenous musical practices with Western notation. The discipline of Ethnomusicology has seen Francis Densmore[3], W.E.B DuBois[4], and many other musicologists attempt this. A common thread among all these examples is that the attempt is never quite enough to capture the quintessence of indigenous musical traditions. They introduce such complex rhythms, and attempt to give different tempo markings for different parts, and the shoe never quite fits.

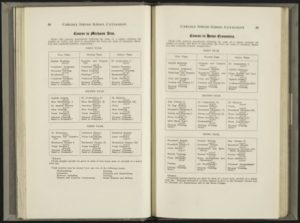

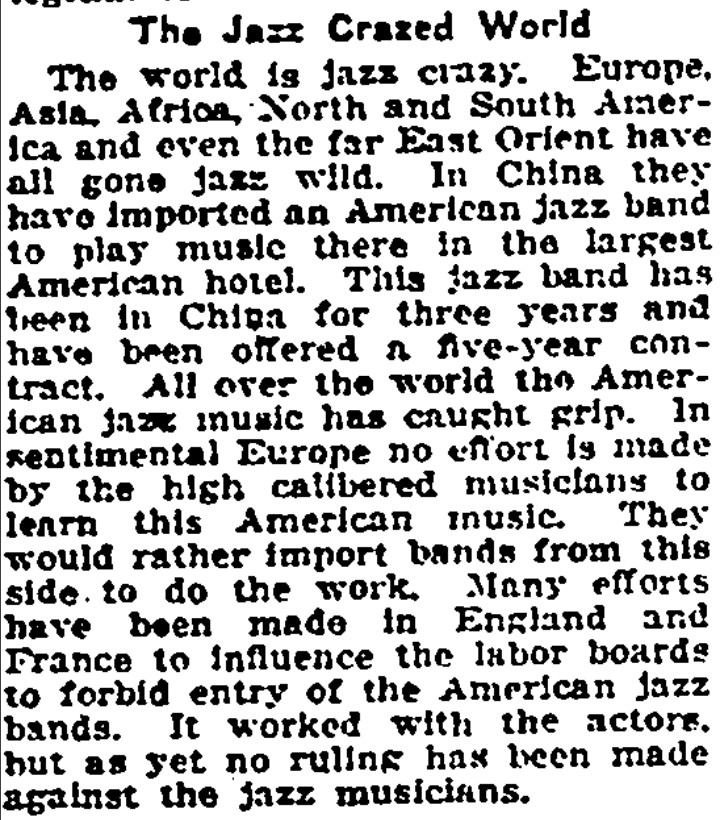

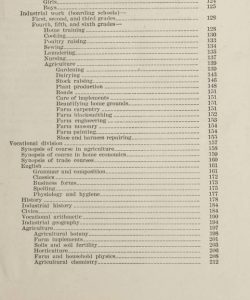

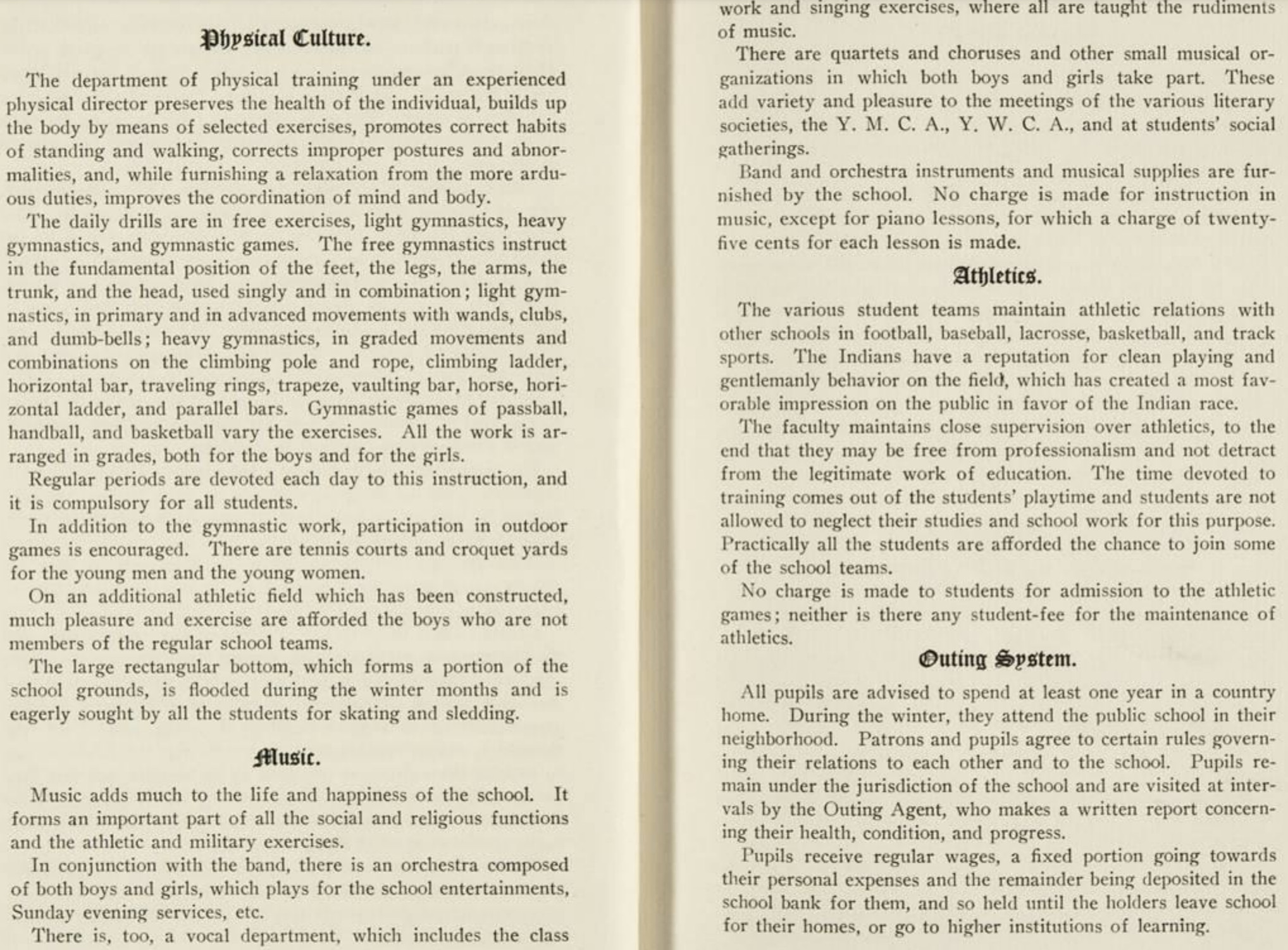

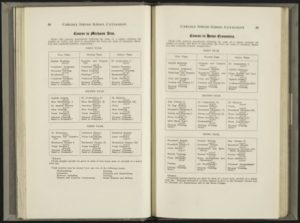

(Click on it to see a better image) A syllabus for students going through the Carlisle Indian School

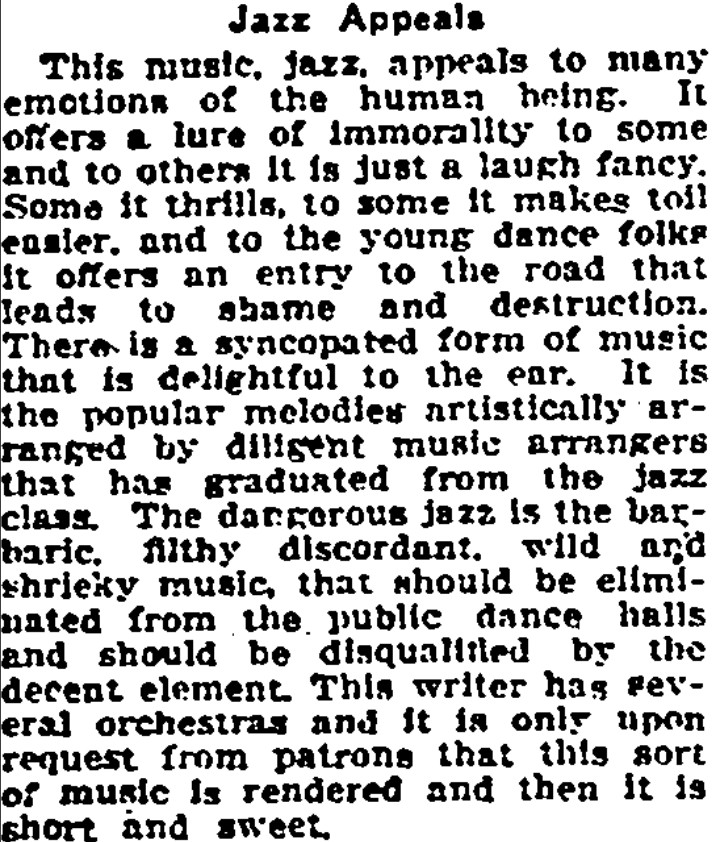

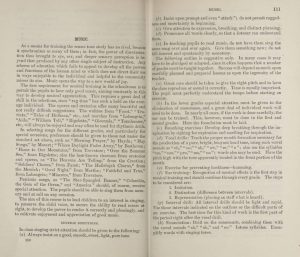

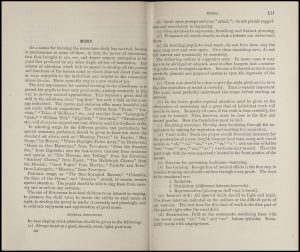

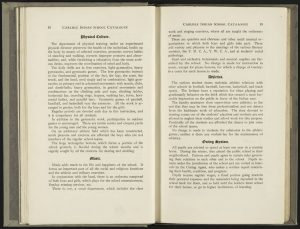

In the document above, you can see an attempt to Americanize indigenous children with this academic plan. This was called the Carlisle Indian School Project, and it was the first government-run boarding school in 1879.[5] Over 180 indigenous children died while attending this conversion school. Notice that in the fall semester of the first year, there is a class based on hygiene. This to me shows that the creators of this curriculum believed the people of indigenous cultures are dirty and need to be taught how to clean themselves. Not very kind and welcoming to my understanding. Below you will see a page outlining the musical education that these kids will receive. They speak of music being a good tool for happiness and religious worship, Christian worship. These kids will also go through the school’s orchestra or band program while having their identities stripped from them.

(Click on it to see it better) Rationale for music education in Carlisle Indian Industrial School

The theme of White Saviorism is not subtle throughout all the sources provided above. We can see it in the work done by Father Emile, and through the Carlisle Indian School Project. It went so far as many students who ‘attended’ the school believed that the only way to save ingenious culture was to shed all practices and dive deep into white culture. Common phrases were “Kill the Indian, Save the man.”[6]

[1] Petitot, Father, Emile. 1862-1889. Chants indiens du Canada Nord-Ouest [manuscript]: recueillis, classés et notés par Emile Petitot, prêtre missionnaire au Mackenzie, de 1862-1882, 1889. [Manuscript]. At: Place: The Newberry Library. VAULT box Ayer MS 715. Available through: Adam Matthew, Marlborough, American Indian Histories and Cultures, http://www.aihc.amdigital.co.uk/Documents/Details/Ayer_MS_715 [Accessed October 24, 2023].

[2] Moir, John S. 2003. “Biography – PETITOT, ÉMILE – Volume XIV (1911-1920) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography.” Www.biographi.ca. 2003. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/petitot_emile_14E.html.

[3] Densmore, Frances. 1929. Pawnee Music. Da Capo Press.

[4] DuBois, W.E.B. 1903. “‘The Sorrow Songs,’ from the Souls of Black Folk.” Teaching American History. 1903. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/the-sorrow-songs/.

[5] Carlisle Indian School Project. n.d. “Carlisle Indian School Project | Richard Henry Pratt Carlisle Indian School.” Carlisle Indian School Project. https://carlisleindianschoolproject.com/past/.

[6] Ibid

Works Cited

Carlisle Indian School Project. n.d. “Carlisle Indian School Project | Richard Henry Pratt Carlisle Indian School.” Carlisle Indian School Project. https://carlisleindianschoolproject.com/past/.

Carlisle Indian Industrial School. 1915. Catalogue and synopsis of courses, United States Indian School, Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Carlisle: Carlisle Indian Press. Available through: Adam Matthew, Marlborough, American Indian Histories and Cultures, http://www.aihc.amdigital.co.uk/Documents/Details/Ayer_389_C2_C2_1915 [Accessed October 24, 2023].

Densmore, Frances. 1929. Pawnee Music. Da Capo Press.

DuBois, W.E.B. 1903. “‘The Sorrow Songs,’ from the Souls of Black Folk.” Teaching American History. 1903. https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/the-sorrow-songs/.

Moir, John S. 2003. “Biography – PETITOT, ÉMILE – Volume XIV (1911-1920) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography.” Www.biographi.ca. 2003. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/petitot_emile_14E.html.

Petitot, Father, Emile. 1862-1889. Chants indiens du Canada Nord-Ouest [manuscript]: recueillis, classés et notés par Emile Petitot, prêtre missionnaire au Mackenzie, de 1862-1882, 1889. [Manuscript]. At: Place: The Newberry Library. VAULT box Ayer MS 715. Available through: Adam Matthew, Marlborough, American Indian Histories and Cultures, http://www.aihc.amdigital.co.uk/Documents/Details/Ayer_MS_715 [Accessed October 24, 2023].

Giddens’ calls for diversifying country and folk music speaks indirectly to the fact that this type of music is very homogenous. While other factors may be at play, it’s clear to see that Francis would have a hard time doing well in the country music genre. Despite this, he succeeded.

Giddens’ calls for diversifying country and folk music speaks indirectly to the fact that this type of music is very homogenous. While other factors may be at play, it’s clear to see that Francis would have a hard time doing well in the country music genre. Despite this, he succeeded.

“Legends and Music of the Navajos” is an article written by Fredrick Starr and published in

“Legends and Music of the Navajos” is an article written by Fredrick Starr and published in