The Native American Boarding Schools here in the United States and Canada are known to be one of the most culturally tragic places in all of U.S. history. Their practices diminished and destroyed cultures that were present centuries before the white Europeans’ settlement On Native American land. These practices included the punishment of students who spoke their Native Language, cutting their hair, which was deemed spiritually important, and most tragically, stripping them of their families and their homes to force them to Western living. Another interesting, and also tragic, was the intense acclimation and forceful immersion of introducing Western Music to the Native American children within the school.

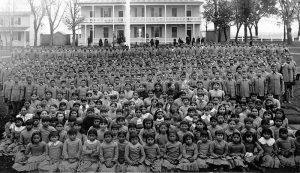

Carlisle Pennsylvania is home to one of the many Native American Boarding Schools in the United States. The first thing that drew me to these sources in particular were the pictures of the students transitioning from what we know as their Native attire, to then presenting themselves through a Western aesthetic and dress. The obvious pride the school had for the students that “successfully”

transitioned from the school also exudes the amount of pride that the faculty had in believing their attempts were successful and meaningful. Although the pride the faculty had was however very present and true, this does not justify their horrific attempts to erase Native American culture.

United States Indian Industrial School, Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Indigenous Histories and Cultures in North America. (n.d.).

The Carlisle Native American Boarding School also took much pride in their music program as that was another way they believed they could control the Native American children, was by forcing them through Western Music Education. Here, a picture showing (although not confirmed, I can logically hypothesize because she was listed as the only music educator on the campus), Miss Verna Dunagan teaching a young Native American student how to play the piano.

United States Indian Industrial School, Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Indigenous Histories and Cultures in North America. (n.d.).

Further into the source, pictures of young male Native American students participating in what is known today as concert bands. These musical practices were used to separate the students further from their culture. The primary source states, “Music divine soothes even the savage beast (not original)”.

Therefore, further perpetuates the racist ideology that Native Americans were not seen nor respected as human beings, but rather more comparable to animals. By using Western canon and music ensembles as a means of control, it drove students further away from their Native culture.

United States Indian Industrial School, Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Indigenous Histories and Cultures in North America. (n.d.).

Although I can argue and state that the erasure of Native American culture in Carlisle was terrible and the use of music was wrongful and forceful, I am also a participant of a wind ensembles whose institution currently sits atop a hill that formerly (and rightfully) belonged to the Wahpekuteh Band of the Dakota Nation. Acknowledging this history does not take away from the horrid atrocities done to Native Americans, I acknowledge and understand the privilege my background has sand the harm it has caused. When reflecting upon these practices, we can also begin to question the true nature of American Music. Whether music was developed within our country or not, the intention in which it was created (or forced) is to control the sound of our country.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iRTURifvbxQ

Sources:

Documents. Documents | Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center. (1919). https://carlisleindian.dickinson.edu/index.php/documents

United States Indian Industrial School, Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Indigenous Histories and Cultures in North America. (n.d.). https://www.indigenoushistoriesandcultures.amdigital.co.uk/Documents/Detail/united-states-indian-industrial-school-carlisle-pennsylvania/7031457?item=7031485

List of Indian boarding schools in the United States. The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. (n.d.-a). https://boardingschoolhealing.org/list/