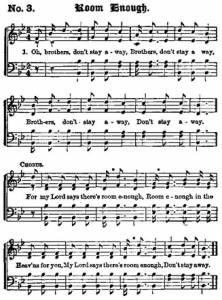

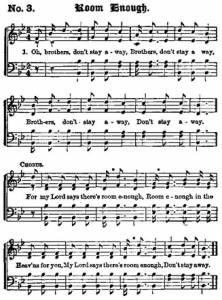

“ Oh, brothers, don’t stay away, . . .

Oh, brothers, don’t stay away, . . .

For my Lord says there’s room enough,

Room enough in the Heav’ns for you,

My Lord says there’s room enough,

Don’t stay away.”

Oh, the irony. As the widely acclaimed Fisk Jubilee Singers preached this message of welcome to thousands of concertgoers, yes, they themselves were met with respect and praise by audiences, but all too often they were also greeted with closed doors.

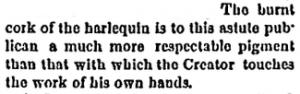

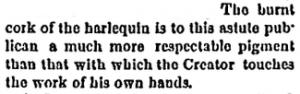

In 1872, only a year after the ensemble began touring the United States and only a few days after receiving “continuous ovation” as guests of the governor of Connecticut, they were turned out of a tavernkeeper’s hostelry. When the Jubilee Singers booked the rooms, he assumed they were a company of blackface minstrels. Upon discovering they were the real deal, not a group of white people engaged in cruel mimicry, he could no longer stomach hosting them. A scathing account of this incident appearing in the March 14, 1872, edition of New York’s The Independent mocks the “publican” tavernkeeper for showing more respect to the “burnt cork of the harlequin,” the blackface of minstrelsy, than the “pigment . . . of [the Creator’s] own hands”:

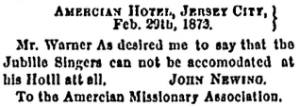

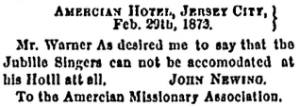

A similar incident, layered in even greater irony, occurred in Jersey City later that same year. Mr. Warner, the proprietor of the American House, a place most would assume to be welcoming to Americans of all colors, had a misspelled cable sent to the Jubilee Singers’ sponsor, the Amercian [sic] Missionary Association, saying:

A similar incident, layered in even greater irony, occurred in Jersey City later that same year. Mr. Warner, the proprietor of the American House, a place most would assume to be welcoming to Americans of all colors, had a misspelled cable sent to the Jubilee Singers’ sponsor, the Amercian [sic] Missionary Association, saying:

After insulting the intellect of Mr. Warner and his clerk, The Independent writer rightly wrote, ” Somebody ought to teach this patriot to spell “American” a little less violently.”

In 1880, they were refused at the St. Nicholas Hotel in Abraham Lincoln’s hometown of Springfield, IL. The Springfield audience greeted this news with hisses and cries of “shame!”

Perhaps the greatest example of a mixed welcome occurred two years later during their visit to Washington, D.C. After they were turned out of numerous hotels in the nation’s capital, they wandered the city until midnight, when they managed to find lodging in private homes. A few days later, they were at the White House at the invitation of President Chester A. Arthur. The Singers brought the president to tears with a performance of “Steal Away to Jesus” and the Lord’s Prayer. “I have never in my life been so much moved,” said the president.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lj6Jm7V9g6E

Honestly, I am disgusted with such behavior. After the Emancipation Proclamation, the Civil War, and the Civil Rights Acts of 1866 and 1875, I would hope that African Americans would be treated with more respect and dignity. Instead I see a distinct laziness shown by the public. Before the war, slaves would entertain Southerners at the plantation house, performing for no money and being told where they could and couldn’t stay. After the war, freedmen would entertain Northerners at concert halls, performing for money and being told where they could and couldn’t stay.

As a culture, we seem to deal best with small changes: from plantation houses to concert halls, from no money to admission prices. We say all we want, using overblown platitudes to demonstrate our support for a cause, but we do as little as we can, avoiding actions that put any kind of strain on our time, budgets, or attitudes, even if a small change on our part could change someone else’s life. Look to the examples of the people of Springfield, President Arthur, and the writers, and go even farther: back up your words with actions. Otherwise, you’re only a hypocrite.

Sources

“THE JUBILEE SINGERS.” The Independent …Devoted to the Consideration of Politics, Social and Economic Tendencies, History, Literature, and the Arts (1848-1921) 24, no. 1215 (Mar 14, 1872): 4. http://search.proquest.com/docview/90171741?accountid=351.

“THE JUBILEE SINGERS AND THE WASHINGTON LANDLORDS.” New York Evangelist (1830-1902) 53, no. 12 (Mar 23, 1882): 2.

“THE JUBILEE SINGERS AT THE HOME AND TOMB OF LINCOLN.” Christian Union (1870-1893) 22, no. 8 (Aug 25, 1880): 156. http://search.proquest.com/docview/137032063?accountid=351.

Marsh, J. B. T. The Story of the Jubilee Singers: With Their Songs. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1876. Accessed February 23, 2015. https://archive.org/.

“President Arthur and the Jubilee Singers.” Church’s Musical Visitor (1871-1883) 11, no. 6 (03, 1882): 162. http://search.proquest.com/docview/137466484?accountid=351.http://search.proquest.com/docview/125358571?accountid=351.

Oh, brothers, don’t stay away, . . .

Oh, brothers, don’t stay away, . . .

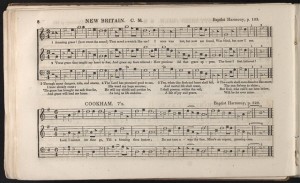

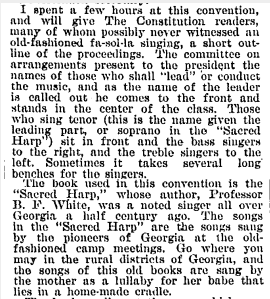

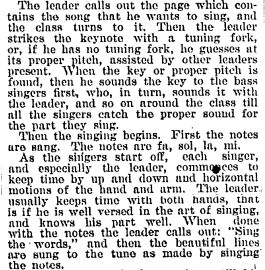

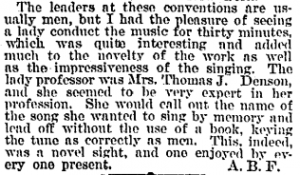

nging was mainly found in the Protestant sect of Christianity. Shape notes reinforce the importance of congregational style of singing in church, allowing for a broader inclusion of church-goers.

nging was mainly found in the Protestant sect of Christianity. Shape notes reinforce the importance of congregational style of singing in church, allowing for a broader inclusion of church-goers. The volume is composed of very beautiful melodies; and harmonies of almost unequalled richness… The tunes are admirably adapted to the effective expression of poetry, a circumstance upon which the happiest effect of Christian Psalmody depend.” A boasting review of a simple style of music, which goes to show the nature of music during this time period in America. Neither monophonic nor polyphonic, this unique style, which is heterophonic in texture, has a surprising sound that is unfamiliar, even to a trained ear. The more popular hymnody has a far more recognizable polyphonic texture that most trained and un-trained ears are accustomed to.

The volume is composed of very beautiful melodies; and harmonies of almost unequalled richness… The tunes are admirably adapted to the effective expression of poetry, a circumstance upon which the happiest effect of Christian Psalmody depend.” A boasting review of a simple style of music, which goes to show the nature of music during this time period in America. Neither monophonic nor polyphonic, this unique style, which is heterophonic in texture, has a surprising sound that is unfamiliar, even to a trained ear. The more popular hymnody has a far more recognizable polyphonic texture that most trained and un-trained ears are accustomed to.

![[Francis Johnson.]](http://images.nypl.org/index.php?id=1257971&t=r)

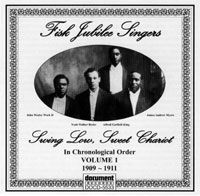

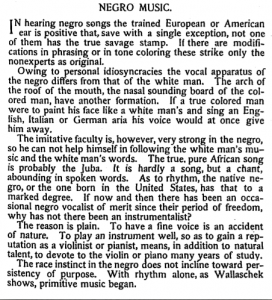

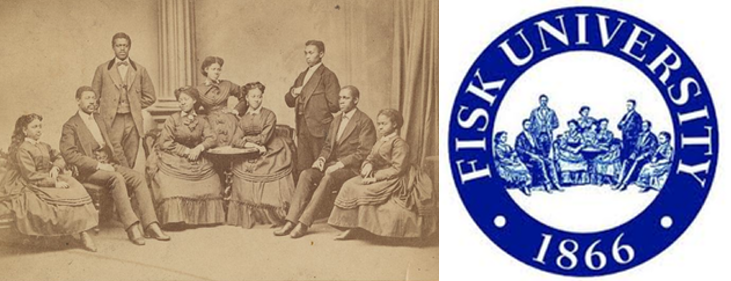

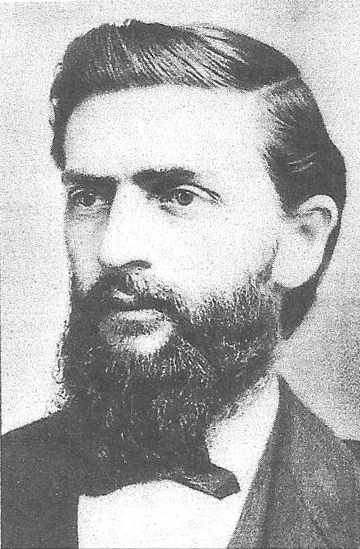

George L. White was originally hired to serve as Fisk’s treasurer, but also found his way into the music classroom. Noticing the institution’s need for income, the treasurer turned music professor also became the school’s first director of choirs. In 1871, White established a choir of freed slaves that he later named the Jubilee Singers. The choir’s purpose was to go and tour the country to raise money for the university. Ella Shepard, the ensemble’s pianist, described the intentions and drive of White was “to sing the money out of the hearts and pockets of the people,” and with that, on October 6, 1871, the choir left Nashville on their first benefit concert tour of the Midwest.

George L. White was originally hired to serve as Fisk’s treasurer, but also found his way into the music classroom. Noticing the institution’s need for income, the treasurer turned music professor also became the school’s first director of choirs. In 1871, White established a choir of freed slaves that he later named the Jubilee Singers. The choir’s purpose was to go and tour the country to raise money for the university. Ella Shepard, the ensemble’s pianist, described the intentions and drive of White was “to sing the money out of the hearts and pockets of the people,” and with that, on October 6, 1871, the choir left Nashville on their first benefit concert tour of the Midwest. able to return to Nashville with $20,000 to be put into the institution. With the profit of their first tour, Fisk University was able to build it’s first permanent campus building, which was named Jubilee Hall and still serves the university to this day. So what exactly did the Jubilee Singers do to make their tour so successful? Simply put, they sang what they knew and what the people wanted to hear.

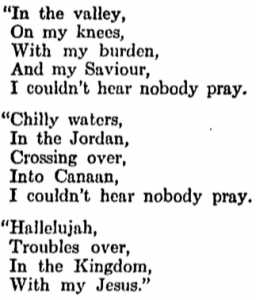

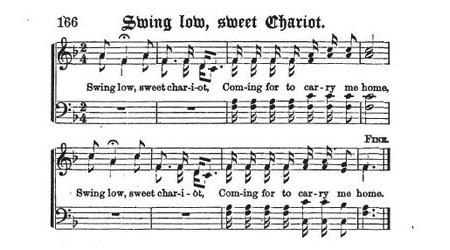

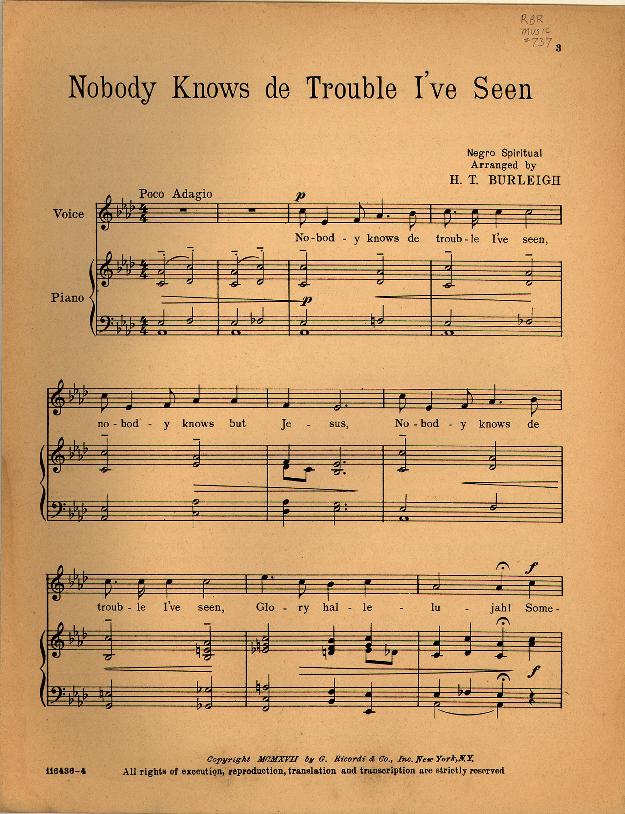

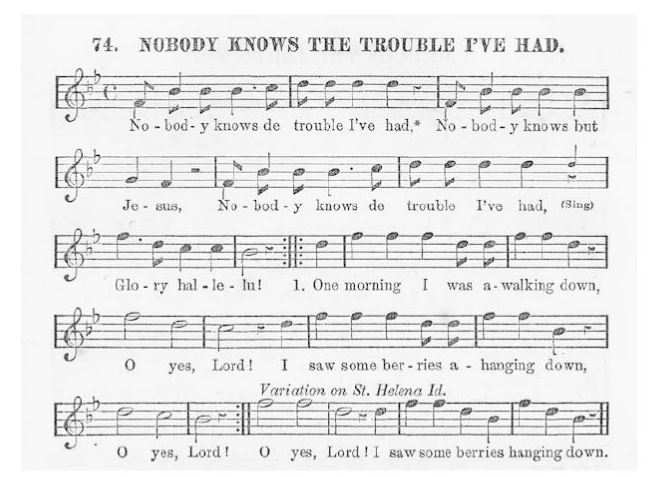

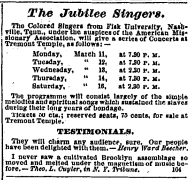

able to return to Nashville with $20,000 to be put into the institution. With the profit of their first tour, Fisk University was able to build it’s first permanent campus building, which was named Jubilee Hall and still serves the university to this day. So what exactly did the Jubilee Singers do to make their tour so successful? Simply put, they sang what they knew and what the people wanted to hear. are capable of singing ‘popular music’,” that had nothing to do with their success. What consistently worked for the ensemble was to defer to their “native, religious songs.” Described in one concert advertisement as the “simple melodies and spiritual songs which sustained the slaves during their long years of bondage,” the music of the Jubilee Singers captivated audiences with their novel sound and religious messages. When asked about their music by members of the public, the singers would respond that “it was never written down” and that is passed down “from generation to generation” within their families. This repertoire, coined “slave songs” would not only carry the ensemble through a successful tour, but also skyrocket them to the national and international stage.

are capable of singing ‘popular music’,” that had nothing to do with their success. What consistently worked for the ensemble was to defer to their “native, religious songs.” Described in one concert advertisement as the “simple melodies and spiritual songs which sustained the slaves during their long years of bondage,” the music of the Jubilee Singers captivated audiences with their novel sound and religious messages. When asked about their music by members of the public, the singers would respond that “it was never written down” and that is passed down “from generation to generation” within their families. This repertoire, coined “slave songs” would not only carry the ensemble through a successful tour, but also skyrocket them to the national and international stage.

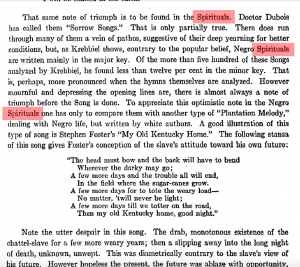

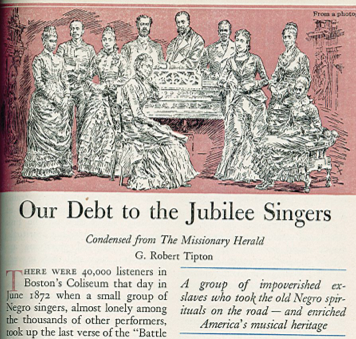

Regardless of your viewpoint on the ethics of choral repertoire when it comes to “selling” sound, the Fisk University Jubilee Singers have surely made their mark on our country’s history. More than 75 years after the Jubilee Singers inaugural tour, G. Robert Tipton wrote an article for The Missionary Herald in 1947, which was later re-published in Reader’s Digest in 1949, titled “Our Debt to the Jubilee Singers.” The article goes through a brief history of the ensemble from their establishment through their first European tour, but what I found most interesting was the summary sentence provided on the front page of the article. Tipton writes that the Jubilee Singers are “a group of impoverished ex-slaves who took the old Negro spirituals on the road – and enriched America’s musical heritage.” There is no doubt that the work of the Fisk University Jubilee Singers has not only enriched our nation’s musical antiquity, but quite possibly assisted in the preservation of the “slave song” genre that is so deeply rooted in America’s history.

Regardless of your viewpoint on the ethics of choral repertoire when it comes to “selling” sound, the Fisk University Jubilee Singers have surely made their mark on our country’s history. More than 75 years after the Jubilee Singers inaugural tour, G. Robert Tipton wrote an article for The Missionary Herald in 1947, which was later re-published in Reader’s Digest in 1949, titled “Our Debt to the Jubilee Singers.” The article goes through a brief history of the ensemble from their establishment through their first European tour, but what I found most interesting was the summary sentence provided on the front page of the article. Tipton writes that the Jubilee Singers are “a group of impoverished ex-slaves who took the old Negro spirituals on the road – and enriched America’s musical heritage.” There is no doubt that the work of the Fisk University Jubilee Singers has not only enriched our nation’s musical antiquity, but quite possibly assisted in the preservation of the “slave song” genre that is so deeply rooted in America’s history.