It’s no wonder that Americans have a narrow, stereotyped understanding of Native American song. On the one hand, there are mass media representations that run from the antiquated and embarrassing…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Etv-TpqLvlc&feature=youtu.be&t=2m1s

… to the downright confusing – I’m thinking especially of all the conflations between Indian and Ashkenazi Jewish musical culture in the 1920s and 1930s, including this one, and this one (at the very end). In fact, mass media’s propensity to get Indian song wrong is so cliché that the stereotyping itself has been parodied, most famously in the irreverent Fox cartoon Family Guy:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UG5oViuaGv0

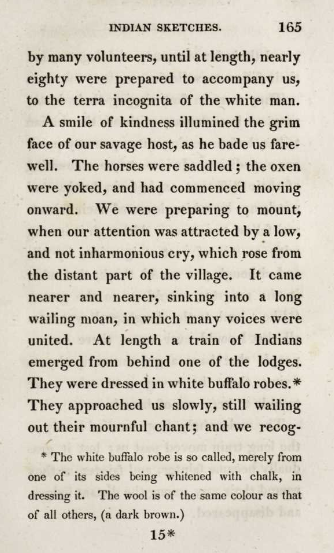

It’s not so hard to see where these misunderstandings come from. From the colonial era to the present day, the majority of Americans have never encountered Native American song themselves; they have mainly read accounts of it written by others. For example, Chicago’s Newberry Library preserves an 1835 account by John T. Irving, Jr. (accessible via the Adam Matthew database, specifically its “American West” collection) that describes an expedition to the Pawnee Tribes. We “hear” music through Irving’s ears, for example in this description of a group of Indians assembling before a journey:

Likening the Indians’ song to a “low, and not inharmonious cry,” a “wailing moan,” and a “mournful chant,” Irving doesn’t really tell us what the “dirge” or “death song” sounds like. Rather, he sets the sounds he heard apart from what his readers might know; he renders the Native American song utterly Other.

It’s unfortunate that accounts like Irving’s have been more influential than systematic, respectful attempts to document Native American song, like that of Frances Densmore. A native of Minnesota, Densmore undertook an enormous study of Native American culture in the late 19th and early 20th centuries under the aegis of the Bureau of American Ethnology, a branch of the Smithsonian Institution. Densmore’s prescience about the misrepresentations referenced above borders on the prophetic. In 1927 she wrote, “There is danger that the future will form its opinions of Indians from the sentimental movies and the theater music when the Indian is seen through the bushes. Neither the “love lyric” nor theater tom-tom music are genuinely Indian, in the best sense” (Qtd. in this Smithsonian Institute online archive; see footnote 5 for archival citation).

Building on the pioneering work of Alice Fletcher, another ethnologist and collector of Indian Song, Densmore published dozens of book-length accounts of music making by individual tribes, including a volume on Pawnee music.

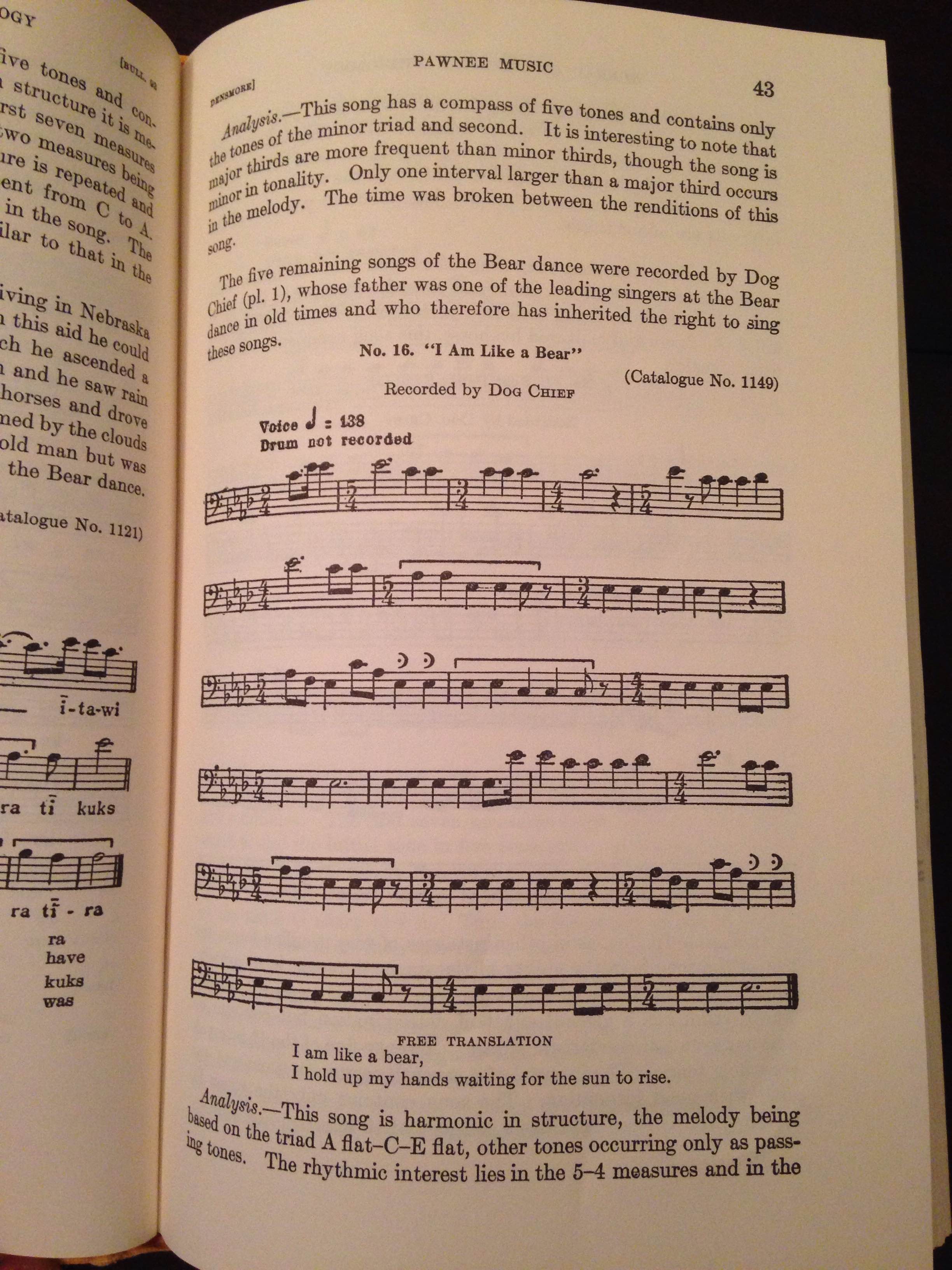

Her description of Pawnee music is nothing like Irving’s. Here’s an excerpt: “An important point, made evident in this comparative analysis, is the individuality of Pawnee music. It is distinct, in its entirety, from the songs of other tribes, though bearing a resemblance to one tribe or another in separate characteristics. The study of Indian music by an established system of analysis shows there are characteristics that are common to Indian songs of various tribes and different from the music of the white race, and also characteristics which distinguish the songs of one tribe from those of another. Among the former is the change of measure-lengths found in many Indian songs and the downward trend of the melody…” (Frances Densmore, Pawnee Music [New York: Da Capo Press, 1972, reprint of 1929 ed. issued as Bulletin 93 of Smithsonian Institution]). Below is another excerpt from the book, this one including a piece she transcribed from a recording made by one of her research associates.

Densmore took Indian music as seriously as it deserved to be taken, and as a result, created an incredibly rich resource for anyone who’d like to know what music Native Americans actually made.

Other Resources:

Books by Densmore at the Carleton and St. Olaf Libraries

Minnesota Public Radio profile of Densmore

Libguide on Densmore created by the Minnesota History Center