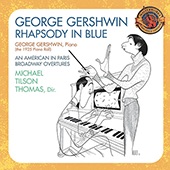

George Gershwin is credited with creating a truly American sound, through the fusion of jazz elements and concert elements. Too often, his works are taken for granted and placed on a pedestal by later listeners who seek to find what is “good” and what is “American”, or are simply repeating the mantra previously espoused. A simple example of this is a quote from the Manitou Messenger from 1950. In describing the music for a St. Olaf Band concert, the author states that “Concluding the program are some familiar selections from “Porgy and Bess” by George Gershwin who is credited with having best expressed the modern American idiom.”

This statement seems to be thrown out lightly, in order to draw in audiences to the concert. While not inherently wrong, this simple statement fails to capture the turmoil of American identity represented by Porgy and Bess. The Manitou Messenger is far from alone in ascribing blanket claims to music. As seen in the history of blues, jazz, and folk music, we have yet (if ever) to define categorical sounds for each of those topics. Gershwin has entered the vernacular as a truly American composer, but historical context is necessary to frame this claim.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_nFk0tl1TBo

Ellen Noonan presents a holistic take on the history of performances of Porgy and Bess, and the politics involved with them. Because the Manitou Messenger article was written in the 1950, I will look at Noonan’s commentary on the state of Porgy and Bess in the 1950s. Noonan takes a strong stance on the political motives of Porgy and Bess.

“This Cold War Porgy and Bess was not just any opera; it engendered debate on a range of issues about race, representation, and politics. With the State Department briefing cast members to “keep in mind what you’d like your folks at home to read in the press about what you say” and U.S. newspapers covering the tour’s every move, Porgy and Bess was as much an intervention in the domestic politics of race as it was an exercise in creative foreign policy” (187)

Musical elements aside, Porgy and Bess became a driving force in pushing what it meant to be American. As such, the music became accepted into the realm and began to define American music. Noonan goes on to argue that Porgy and Bess mirrors the struggles of black people in the growing era of the Civil Rights movements. The U.S. government’s “propaganda efforts (like the Porgy and Bess tour) intended to convince the world that incidents of racial discrimination and violence were exceptional rather than typical” (189). If this is true, then perhaps Porgy and Bess does represent American music–that which is filled with rich history and suffers from a constant watering down and manipulation to fulfill a national identity.

Wether the identity is organic or fabricated, Porgy and Bess has certainly lent itself to an American musical identity, and it is clear that the message of American greatness trickled down into local college newspapers. A greater understanding of the history of any music is necessary in order to more fully inform a claim for an individual to express “the modern American idiom”.

Bibliography

Gershwin, Bennett, Shaw, Merrill, Stevens, Bennett, Robert Russell, . . . RCA Victor Orchestra, performer. (1950). Porgy and Bess.

Flaten, Anne. “Berglund Directs St. Olaf Band In Winter Concert This Evening”. The Manitou Messenger, No. 15, Vol. 063. February 17, 1950.

Noonan, Ellen. The Strange Career of Porgy and Bess : Race, Culture, and America’s Most Famous Opera. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012. Accessed October 30, 2017. ProQuest Ebook Central.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-1600746-1240680184.jpeg.jpg)

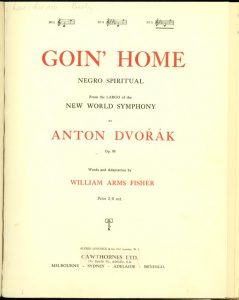

by William Arms Fisher of Anton Dvořák’s New World Symphony (No. 9, mvt II Largo, specifically). Personally, I love the symphony and have enjoyed listening to it for many years, but I can’t help but wonder now about the complicated philosophies of Dvořák and this adaptation of his work which place the work not just as a well-known music history class example to memorize, but a work that has juxtaposed good intention with possible misguided ideology.

by William Arms Fisher of Anton Dvořák’s New World Symphony (No. 9, mvt II Largo, specifically). Personally, I love the symphony and have enjoyed listening to it for many years, but I can’t help but wonder now about the complicated philosophies of Dvořák and this adaptation of his work which place the work not just as a well-known music history class example to memorize, but a work that has juxtaposed good intention with possible misguided ideology.

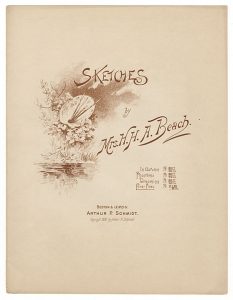

In September 2017, the New York Times honored Amy Beach’s 150th birthday with an article on her life and works. The biggest takeaway I found in this article was that her “Gaelic” Symphony shot her to compositional fame, but no orchestras have programmed hersymphony or any of her orchestral works for this season. While Beach experienced sexism at the height of her career, it is clear that sexism in classical music is still alive and well when none of our major orchestras will honor her works on this anniversary.

In September 2017, the New York Times honored Amy Beach’s 150th birthday with an article on her life and works. The biggest takeaway I found in this article was that her “Gaelic” Symphony shot her to compositional fame, but no orchestras have programmed hersymphony or any of her orchestral works for this season. While Beach experienced sexism at the height of her career, it is clear that sexism in classical music is still alive and well when none of our major orchestras will honor her works on this anniversary.

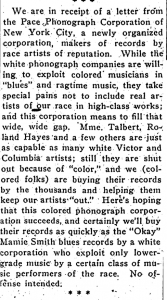

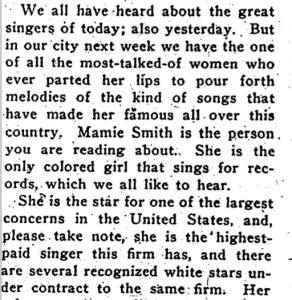

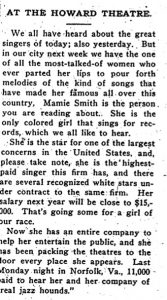

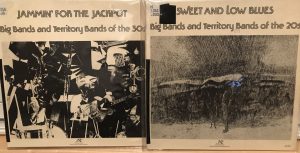

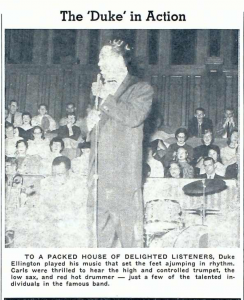

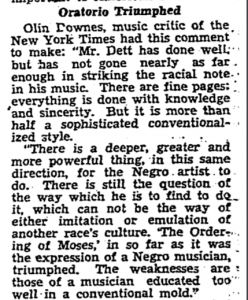

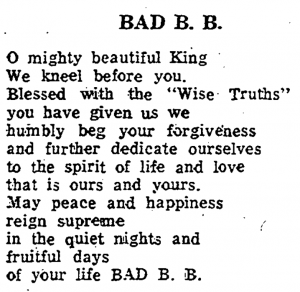

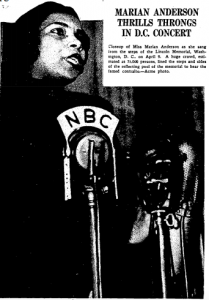

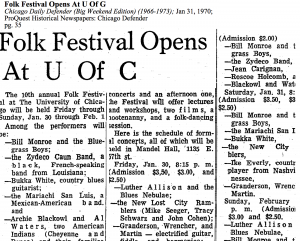

Image Courtesy of The Chicago Defender May 1937 Issue

Image Courtesy of The Chicago Defender May 1937 Issue

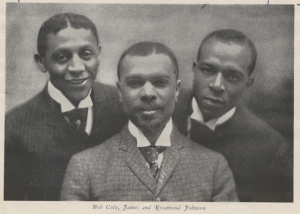

Eventually, Sherman Dudley’s circuit of theaters for African American performers, the “Consolidated Circuit,” merged into the Theater Owners Bookers Association (TOBA)

Eventually, Sherman Dudley’s circuit of theaters for African American performers, the “Consolidated Circuit,” merged into the Theater Owners Bookers Association (TOBA)