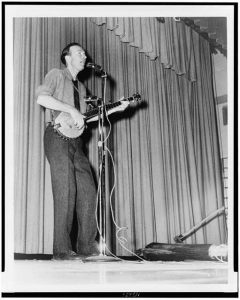

Pete Seeger performing on stage with a banjo in Yorktown, NY.1

Pete Seeger was an American singer, songwriter, folk song collector, and social activist. After his death in 2014, most people today credit Pete Seeger as “one of the most important American musical voices of the 20th century.”2 This reputation that Seeger maintains was not always the case. At one point during his 70 year career, Seeger was a member of the communist party in the United States and was convicted for contempt of Congress after defying the House Un-American Activities Committee in the 1950s.3 He managed to completely revise his reputation during his career and he “lends support to the argument that reputations are radically malleable, even when the figure has not changed dramatically.”

At the beginning of his career in the 1940s, Seeger would often perform at leftist rallies and became well known amongst communist groups. After Seeger began to have accusations of his leftist beliefs, those who were against him had a great effect on his reputation because those who defended Seeger also became the target of attacks. By 1953, Seeger’s record label had dropped him and, his current negative reputation “caused Seeger to be banned from many mainstream venues either because there were outspoken anti-Communists to oppose him or because venues wished to avoid potential controversy.”4

Seeger’s reputation began to change in the 1960s with the resurgence of folk music and emerging social movements. Eventually, the movements Seeger participated in began to gain social favor. While Seeger was shunned from many mainstream performance venues, he performed at colleges instead for a “younger generation that was ready to adopt figures who would challenge the status quo.”5 His music reflected many social concerns of the younger generation and he sang about “the labor movement in the 1940s and 1950s, for civil rights marches and anti-Vietnam War rallies in the 1960s, and for environmental and antiwar causes in the 1970s and beyond.”6 One of his most notable songs is “We Shall Overcome,” which was adapted from old spirituals and became a civil rights anthem.

During the time he was actively releasing music and fighting for these causes which he believed in, he was still ignored and not taken seriously by many in the older generations because they were not taking him seriously. They believed he was “free to sing whatever he likes because this saintly old man can hardly be ‘seriously’ proposing rebellion.”7 They were wrong. This disagreement still happens very frequently in today’s society as well, both in music and other social platforms. There are many in today’s present society that overlook the voices of younger generations and assume no harm can be done or change cannot be made. Many cultures of people are constantly underestimated by those with white superiority who believe they are untouchable until it’s too late to realize they are not.

Bibliography

Bromberg, Minna, and Gary Alan Fine. “Resurrecting the Red: Pete Seeger and the Purification of Difficult Reputations.” Social Forces 80, no. 4 (2002): 1135–55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3086503.

Kavallines, James. [Pete Seeger, full-length portrait, performing on stage at Yorktown Heights High School, Yorktown, N.Y.] / World Journal Tribune photo by James Kavallines. Photograph. Washington, D. C. , February 2, 1967. Library of Congress.

Pareles, Jon. “Pete Seeger, Champion of Folk Music and Social Change, Dies at 94.” The New York Times, January 28, 2014. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/29/arts/music/pete-seeger-songwriter-and-champion-of-folk-music-dies-at-94.html.

Robb, Alice. “The History of Pete Seeger’s Reputation Is the History of the Past 70 Years.” The New Republic, September 26, 2023. https://newrepublic.com/article/116379/pete-seegers-reputation-shows-history-past-70-years.

1James Kavallines, [Pete Seeger, Full-Length Portrait, Performing on Stage at Yorktown Heights High School, Yorktown, N.Y.] / World Journal Tribune Photo by James Kavallines., photograph (Washington, D. C. , February 2, 1967), Library of Congress.

2Alice Robb, “The History of Pete Seeger’s Reputation Is the History of the Past 70 Years,” The New Republic, September 26, 2023, https://newrepublic.com/article/116379/pete-seegers-reputation-shows-history-past-70-years.

3Jon Pareles, “Pete Seeger, Champion of Folk Music and Social Change, Dies at 94,” The New York Times, January 28, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/29/arts/music/pete-seeger-songwriter-and-champion-of-folk-music-dies-at-94.html.

4 Minna Bromberg, and Gary Alan Fine. “Resurrecting the Red: Pete Seeger and the Purification of Difficult Reputations.” Social Forces 80, no. 4 (2002): 1135–55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3086503.

5Minna Bromberg, and Gary Alan Fine. “Resurrecting the Red: Pete Seeger and the Purification of Difficult Reputations.” Social Forces 80, no. 4 (2002): 1135–55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3086503.

6Jon Pareles, “Pete Seeger, Champion of Folk Music and Social Change, Dies at 94,” The New York Times, January 28, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/29/arts/music/pete-seeger-songwriter-and-champion-of-folk-music-dies-at-94.html.

7Minna Bromberg, and Gary Alan Fine. “Resurrecting the Red: Pete Seeger and the Purification of Difficult Reputations.” Social Forces 80, no. 4 (2002): 1135–55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3086503.