On the first day of musicology the class had a candid, inquisitive discussion about the origins of American music. We gracefully came to the conclusion that what we consider American music likely did not start with Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys in the 1940s, and that it is more plausible that American musicking had been going on for hundreds of years before then, as Rhiannon Giddens suggests. We concluded by emphasizing the subjectivity of what American music is, and how identity and power often manipulate our definitions.

In researching early American music for this blog post, I noticed that much of the research I turned up quoted a father and son by the names of John and Alan Lomax. Alan Lomax is quoted as a credible historian and ethnomusicologist of the time who travelled across the US and Haiti documenting and recording local musics. One especially enthusiastic source exclaims that few sources deserve greater praise than him for “the preservation of America’s folk music.” It is astounding that he recorded over 5,000 hours of song recordings from people across the world during his travels which is mostly all accessible through online databases.

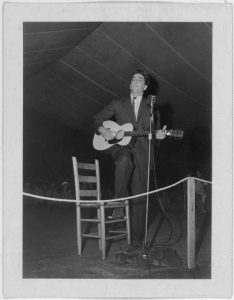

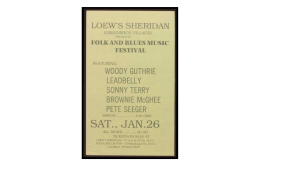

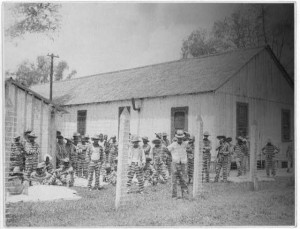

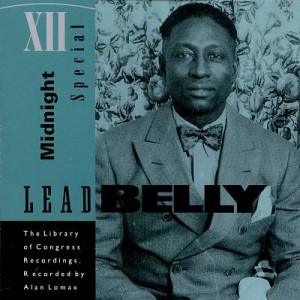

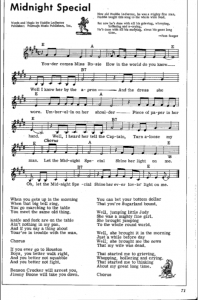

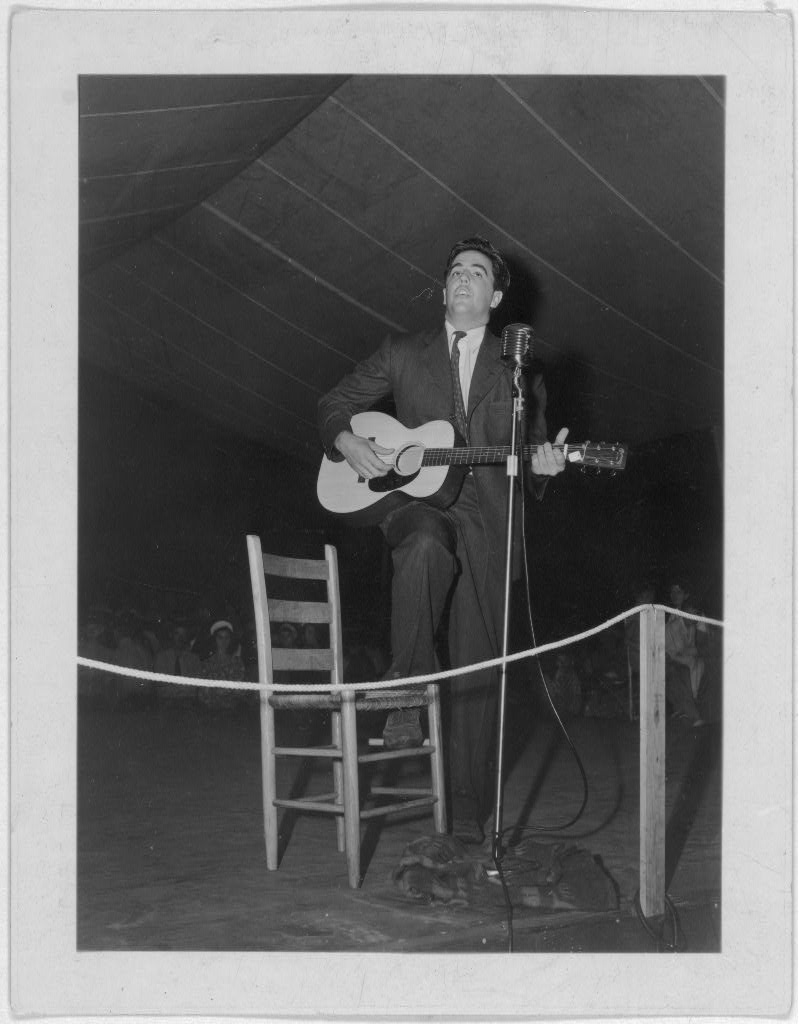

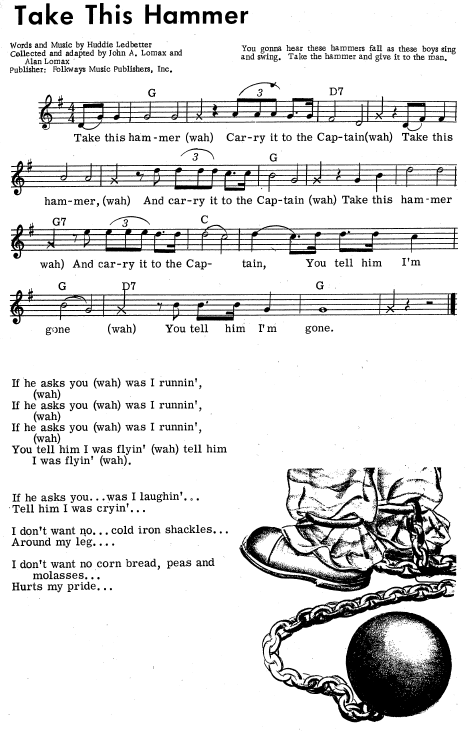

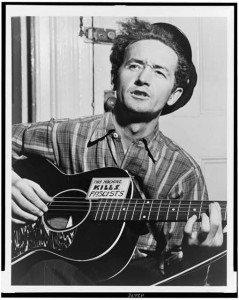

I rested on one particularly interesting set of recordings which features a singer by the stage name of Leadbelly. The story goes that Lomax discovered Leadbelly (Huddie William Ledbetter) and his music when visiting the prisons in Louisiana where he was imprisoned for murder. When he got out, the Lomaxes took him on tours around the United States where he performed and gained popularity to the point where many of his songs are today considered folk classics.

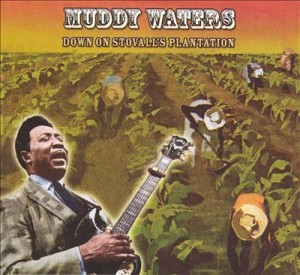

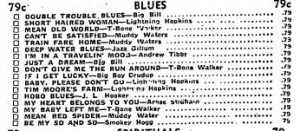

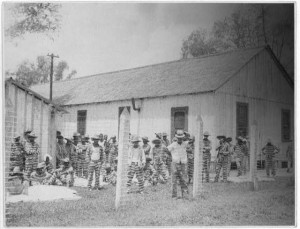

At this time in America during the depression of the 1930s the Lomaxes were in search of a cohesive identity for Americans to find in music. The fact that they looked to cotton plantations, ranches, and segregated prison music was purposeful and undeniably has altered the documentation of American music. However they also altered the music in which Leadbelly was able to perform. Listen to a Leadbelly original, Mr Tom Hughes Town as it was originally recorded in 1934:

https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Crecorded_track%7C286842

…and now listen to this recording which was for the American Record Company:

https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Crecorded_cd%7C1141785

For our purposes, I think it is most important to understand simply that these recordings are much different in their storyline and musical style. The Lomaxes often changed his music or told him to learn new music in order to appeal to audiences, specifically Whiter audiences. The second recording is thought to appeal more to Northern, whiter audiences as it is less “sharp-sounding.” In order to gain popularity, they would even have him dress in his prison clothes and purposefully include his backstory in shows to get people interested.

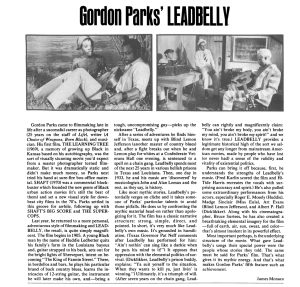

Retrieved from, Monaco, J. (1977). Gordon Parks’ LEADBELLY. Cinéaste, 8(2), 40–40. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41685809

This is a stark contrast to the movie made about him some 40 years later in the 1970s in which he ends up in prison for playing music in a segregated country club. (see newspaper clipping attached)

I think the alteration of Leadbelly’s music illustrates importantly how progressivism may act as a convenient disguise for perpetuating the inequalities that such an ideology seeks to overcome.

Sources

Lomax, Alan, 1915-2002, by Jason Ankeny, All Music Guide. (2001). In All Music Guide: The Definitive Guide to Popular Music (p. 1). San Francisco, CA: Backbeat Books. Retrieved from Music Online: African American Music Reference database.

Field Recordings Vol. 5: Louisiana, Texas, Bahamas (1933-1940) [Streaming Audio]. (1998). Document Records. (1998). Retrieved from Music Online: American Music database.

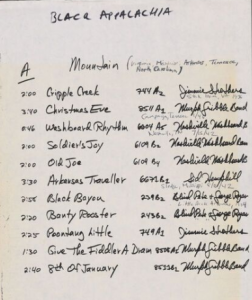

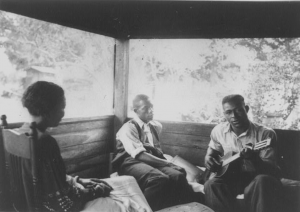

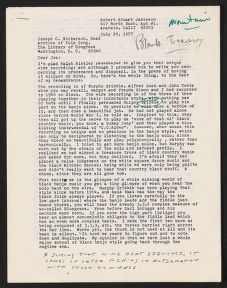

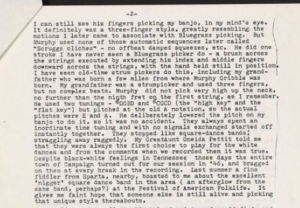

When I found a set of manuscripts collected by Alan Lomax on the playing of musicians in Black Appalachia, the last thing I expected was to end up reading about Earl Scruggs. Nevertheless, this letter from Stu Jamieson on field recordings done in 1946 of a trio of Black Appalachian musicians connected directly into our discussions of bluegrass music from Thursday’s class. The recordings this letter is referencing are of Murphy Gribble, John Lusk, and Albert York on banjo, fiddle, and guitar respectively. Apparently a banjo player himself and familiar with the rise of bluegrass by the time this letter was written in about 1978, Jamieson writes to a friend and scholar at the Library of Congress about the Gribble’s particular styles of banjo picking and fingering. As with Bill C. Malone, part of the reason his recounting is convincing because of his own study and experience with the styles he discusses.

When I found a set of manuscripts collected by Alan Lomax on the playing of musicians in Black Appalachia, the last thing I expected was to end up reading about Earl Scruggs. Nevertheless, this letter from Stu Jamieson on field recordings done in 1946 of a trio of Black Appalachian musicians connected directly into our discussions of bluegrass music from Thursday’s class. The recordings this letter is referencing are of Murphy Gribble, John Lusk, and Albert York on banjo, fiddle, and guitar respectively. Apparently a banjo player himself and familiar with the rise of bluegrass by the time this letter was written in about 1978, Jamieson writes to a friend and scholar at the Library of Congress about the Gribble’s particular styles of banjo picking and fingering. As with Bill C. Malone, part of the reason his recounting is convincing because of his own study and experience with the styles he discusses.