When I found a set of manuscripts collected by Alan Lomax on the playing of musicians in Black Appalachia, the last thing I expected was to end up reading about Earl Scruggs. Nevertheless, this letter from Stu Jamieson on field recordings done in 1946 of a trio of Black Appalachian musicians connected directly into our discussions of bluegrass music from Thursday’s class. The recordings this letter is referencing are of Murphy Gribble, John Lusk, and Albert York on banjo, fiddle, and guitar respectively. Apparently a banjo player himself and familiar with the rise of bluegrass by the time this letter was written in about 1978, Jamieson writes to a friend and scholar at the Library of Congress about the Gribble’s particular styles of banjo picking and fingering. As with Bill C. Malone, part of the reason his recounting is convincing because of his own study and experience with the styles he discusses.

When I found a set of manuscripts collected by Alan Lomax on the playing of musicians in Black Appalachia, the last thing I expected was to end up reading about Earl Scruggs. Nevertheless, this letter from Stu Jamieson on field recordings done in 1946 of a trio of Black Appalachian musicians connected directly into our discussions of bluegrass music from Thursday’s class. The recordings this letter is referencing are of Murphy Gribble, John Lusk, and Albert York on banjo, fiddle, and guitar respectively. Apparently a banjo player himself and familiar with the rise of bluegrass by the time this letter was written in about 1978, Jamieson writes to a friend and scholar at the Library of Congress about the Gribble’s particular styles of banjo picking and fingering. As with Bill C. Malone, part of the reason his recounting is convincing because of his own study and experience with the styles he discusses.

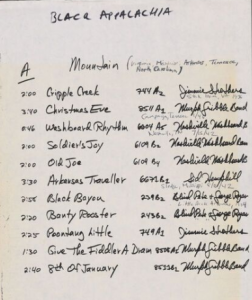

Very few of the recordings referenced are easy to find; however, three songs played by this trio appear on the Black Appalachia CD of Deep River of Song – the same series that supplied our listenings for Black cowboy music (1). The three songs can be seen in the list given to the right, labelled with Murphy Gribble’s name: “Christmas Eve,” “Give the Fiddler a Dram,” and “8th of January.” Notably missing from this set is the solo recording of Gribble that Jamieson spends most of his time discussing.

Perhaps this sort of delving into history is what Rhiannon Giddens did when she started to discover the complex roots of bluegrass, which had been introduced to her as a white genre (2). While it is unlikely that these particular players had much to do with the spreading popularity of this style of play until it developed into bluegrass, Jamieson is certain that they are clues to a more significant history, and that there must have been more musicians who played like Gribble, Lusk, and York. As a broader style, and not simply a characteristic of a single isolated musician (or three), it likely would have spread and been one of the streams which fed into the development of mid-19th century bluegrass. In the letter, Jamieson says that the musicians told him what they were doing was “the way the black folks always played” (3). This discussion and the solo recording of Gribble’s playing are his main pieces of evidence in claiming that there is a “whole world” of black country music that has been missed by white recorders. His excitement is genuine and somewhat infectious, but it seems also to be a bit simplistic. Countless other strands of folk music traditions have not been recorded and preserved exactly as they were, but that does not mean they are completely lost; on the contrary, they exist in the traditions that they helped develop. And there certainly are plenty of recordings of black country musicians that could hold the keys that Jamieson says are missing. He himself admits that he saw “nothing new of note” until he persuaded Gribble to play alone; it’s distinctly possible that a similar style had been recorded, but not independently (3).

I also noted that toward the end of the letter, Jamieson (depicted below) tells his friend who to contact for permission to share the recordings they are discussing with a broader public (4). Any of the musicians who appear on the recordings, or any of their family members, as several of them had passed away by the ti me the letter was written, are not given as contacts. This is not directly relevant to the validity of the story being shared, but it does raise some interesting questions about the ways Jamieson thinks about the music he has recorded, in comparison with other statements about the treatment of black country musicians.

me the letter was written, are not given as contacts. This is not directly relevant to the validity of the story being shared, but it does raise some interesting questions about the ways Jamieson thinks about the music he has recorded, in comparison with other statements about the treatment of black country musicians.

Works Cited:

- Deep River of Song: Black Appalachia. Recorded January 1, 1999. Rounder Records, 1999, Streaming Audio. https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Crecorded_cd%7C1765170.

- Povelones, Robert. “Rhiannon Giddens Keynote Address – IBMA Business Conference 2017.” IBMA, International Bluegrass Music Association, 17 May 2018, ibma.org/rhiannon-giddens-keynote-address-2017/.

- Lomax, Alan. Alan Lomax Collection, Manuscripts, A Recorded Treasury of Black Folk Song, -1981, Black Appalachia. to 1981, 1978. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/afc2004004.ms120226/.

- Wikipedia contributors, “Robert Stuart Jamieson,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Robert_Stuart_Jamieson&oldid=900729296 (accessed September 24, 2019).