Discussion in class lately has focused a lot on what are the right ways to study music that is not from our culture or with things that are unfamiliar to ourselves. While we aim to learn and gain knowledge from those around us we often go about doing so in the wrong ways. I found myself captivated by the need to first look at my own identity before I can even begin to learn from someone else. I think it is important when trying to understand identity you have to understand your own and the significance of that.

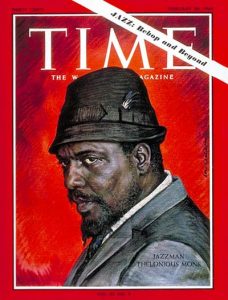

Reading into Duke Ellington, I cam across a book that he wrote about himself. The book spans over 500 pages and is filled with his reflections on every aspect of his musical persona. Speaking in first, second, and third person narrative, Ellington delves into the depths of his music identity. The book is falling apart at the seams and the plastic jacket put on by the library seems to be the only thing keeping it intact. Enjoying the book so much to the point of wanting my own copy I quickly found it near impossible to find a “new” copy of the book and every copy I can across was in similar condition. Skimming through the book one sees it is set up as a performance with multiple “acts” that divide the book up. The “blurb” or synopsis of the book (written by Ellington) draws the reader in with his third person perspective.

The book is falling apart at the seams and the plastic jacket put on by the library seems to be the only thing keeping it intact. Enjoying the book so much to the point of wanting my own copy I quickly found it near impossible to find a “new” copy of the book and every copy I can across was in similar condition. Skimming through the book one sees it is set up as a performance with multiple “acts” that divide the book up. The “blurb” or synopsis of the book (written by Ellington) draws the reader in with his third person perspective.

“My Favorite Tune? The next one. The one I’m writing tonight or tomorrow, the new baby is always the favorite….The author of these words has created some of the best-loved music in the world: ‘Mood Indigo,’ ‘Sophisticated Lady,’ ‘Caravan,’ ‘Take the A Train,’ ‘Solitude.’ More of a performance than a memoir, this book by Duke is Duke, with everything but the soundtrack. He never wanted to write an autobiography and he hasn’t. What he’s done is lay it all down– the times he’s had, the people he’s know. A superior name-dropper, the Duke only drops names he knows– and he’s known them all: Presidents, George Gershwin, Louis Armstrong, Frank Sinatra, Lena Horne, Ella Fitzgerald, Orson Welles, and most especially his own “boys in the band,” Billy Strayhorn, arranger–lyricist who was “my right arm, my left arm, and all the eyes in the back of my head,” plus Sonny Greer, Cootie Williams, Johnny Hodges, and many others. There are short takes: essays on his philosophy of life (Music, Night Life, God and Wisdom, all pass scrutiny); journals of his triumphant tours across the world; and his “Sacred Concerts.” Throughout, he writes with all the elegance, panache, sophistication, and innocence that are marks of his unforgettable music Duke Ellington’s talent radiates a special energy, and a magic that could only evolve from a grandiose love of life. His book, bursting with anecdote and spirits, honors that great gift.”

While the book goes through each “Act” and looks at his tours, the numerous big names he has gotten to know, his personal philosophy of life, and different journal articles about it; it also includes an interview he holds with himself. This was a part I found most fascinating as he conducts a very well done interview with himself that asks questions such as “Do you consider yourself as a forerunner n the advanced musical trends derived from jazz?,” “How do you regard the phenomenon of the black race’s contribution to the U.S. and world culture?,” “What is God for you”, “What does America mean to you,” and so many more.

I was quickly taken by this book and immensely curious to its contents. I found that Duke’s performances have to include the art of writing this autobiography-that-is-not-an-autobiography. This book is valuable information into the life of Duke Ellington. If we could’ve had a book written like this (or maybe spoken aloud) by specific Native American tribes we would learn so much about their perspective of their own music. It’s a great example of quality sources with credible authors. In class (and especially in my education classes) we discuss how everyone is an expert in their life and to their identity. While looking at one individual is not always the best way to learn about a whole group of people it is a great place to start.