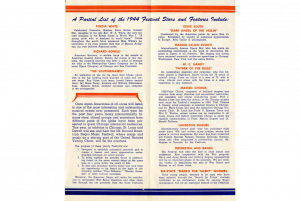

In 1913, Densmore published Teton Sioux Music, a dauntingly large volume containing an analysis of Teton Sioux music and a look into their culture and customs. Unlike many of her other bulletins, articles, and books, this publication includes two personal narratives of tribe members. The stories of Red Fox and Eagle Shield tell of daily life within their communities and formative experiences for these individuals as they grew up. By publishing these stories, Densmore preserves the voices of the individuals she interacted with and gives her audiences a glance into these people’s lives. But these narratives pose more questions about Densmore and her methods than they answer. Why did Densmore include so few of these narratives in her writings? Why did she choose to publish these particular stories? Perhaps it is because both stories are related to songs that Densmore recorded and analyzed. Or, should we hold on to hope that these songs and their stories were included because of a particularly strong bond between Densmore and these two Native men? While we know Densmore must have had some sort of connection to those whom she interacted with as she studied Indigenous music, her publications do not give us a strong sense of these relationships and bonds. Instead, these books offer significant evidence of Densmore’s academic and intellectual strengths. This focus on the analysis and collection is likely a reflection of two of Densmore’s values in research and study. First, a racialized desire to capture as much knowledge about these ‘dying’ community’s music, culture, and customs; and second, a response to the misogyny she likely experienced as a women researcher and academic to publish and analyze as much as humanly possible.

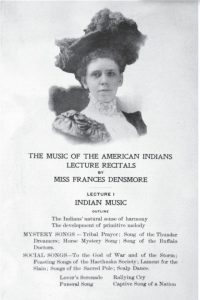

Densmore’s racialized perspective towards her own study is no secret and is clearly reflected in her methods for ethnomusicological study. Just a few examples of this include her notation of Indigenous music using western standards, her desire to take images of native peoples unbeknownst to them, and her choice to use incredibly racist terminology when talking about Native Americans, such as ‘primitive’. In addition, her positionality within academia as a woman also likely impacted the way she chose to engage in study and share her findings. In Travels with Frances Densmore, Michelle Wick Patterson writes about how Densmore towed the lines of the gender norms of her time. By working in music and in the humanities, Densmore continued to engage in ‘women’s work’. This foundation allowed her to give lectures, speeches, and publish academic works which all pushed the bounds of what was acceptable for women to do at this time.

By examining Densmore’s motivations for research, we can begin to learn yet another lesson from the work of this challenging, ractist, and tenacious women. When anaylizing the work of any humanist researcher, it might be just as important to understand their own positionality with in their field along with the positionality of their subjects. For such understanding and knowledge can shed light on the researchers motivations for their own project, and for the reception of it.

Densmore, Frances. Teton Sioux Music. New York, Da Capo Press, 1972.

Patterson, Michelle Wick. “She Always Said, ‘I Heard an Indian Drum’”. Travels with Frances Densmore: Her Life, Work, and Legacy in Native American Studies. University of Nebraska Press, 2015, 29-64.

White, Bruce. “Familiar Faces: Densmore’s Minnesota Photographs”. Travels with Frances Densmore: Her Life, Work, and Legacy in Native American Studies. University of Nebraska Press, 2015, 316-350.