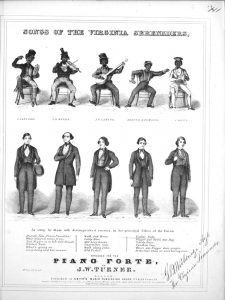

The first minstrel shows performed in the 1830s by white performers donning blackface and tattered clothing imitated and mimicked enslaved African Americans in the south. These performances would characterize African Americans as lazy, ignorant, hypersexual, and prone to thievery and cowardice. Historians have said that the reason these racist stereotypes and caricatures became so popular was to help make poorer and working-class whites feel better about themselves by putting down African Americans.

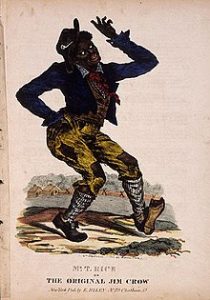

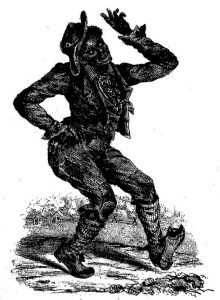

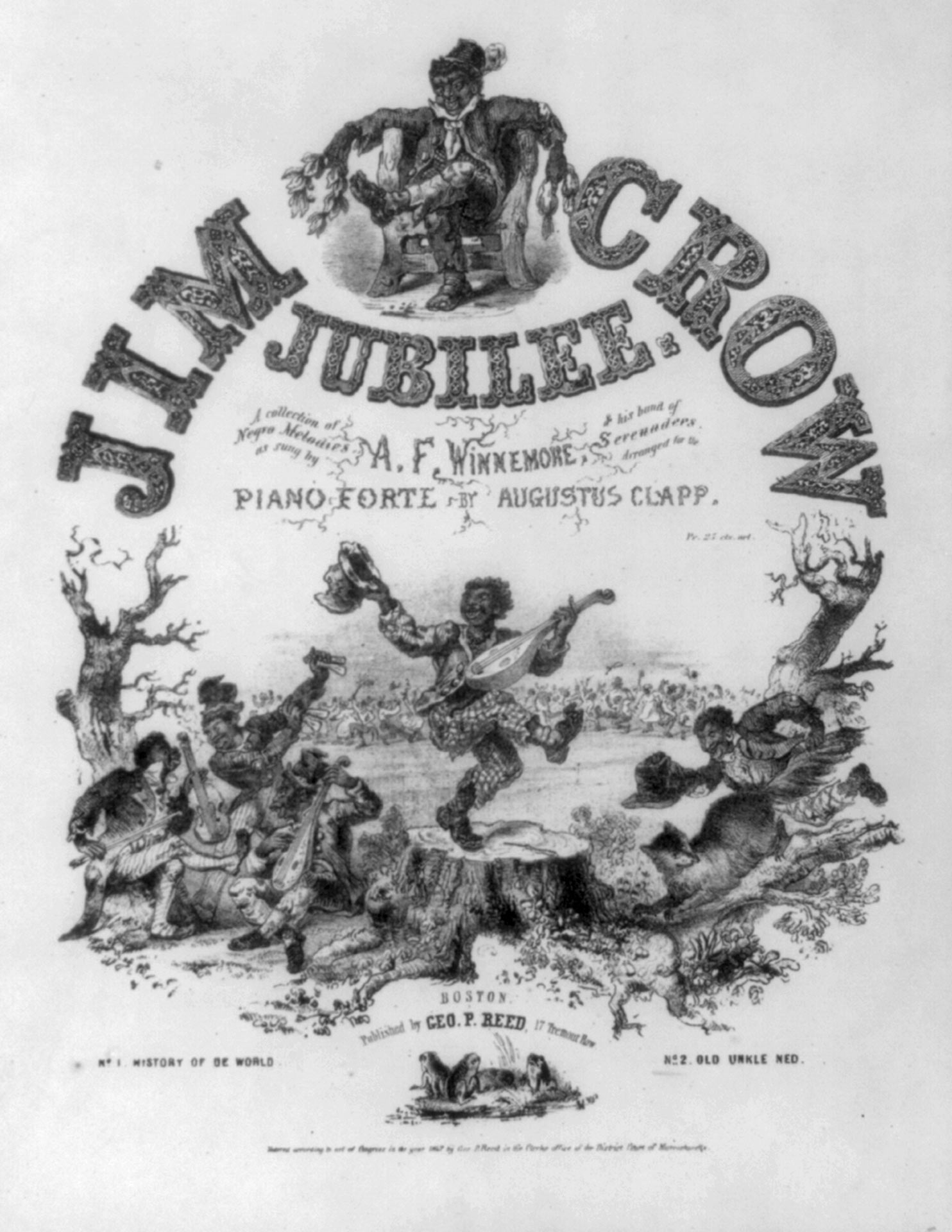

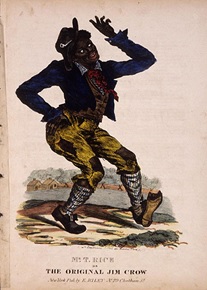

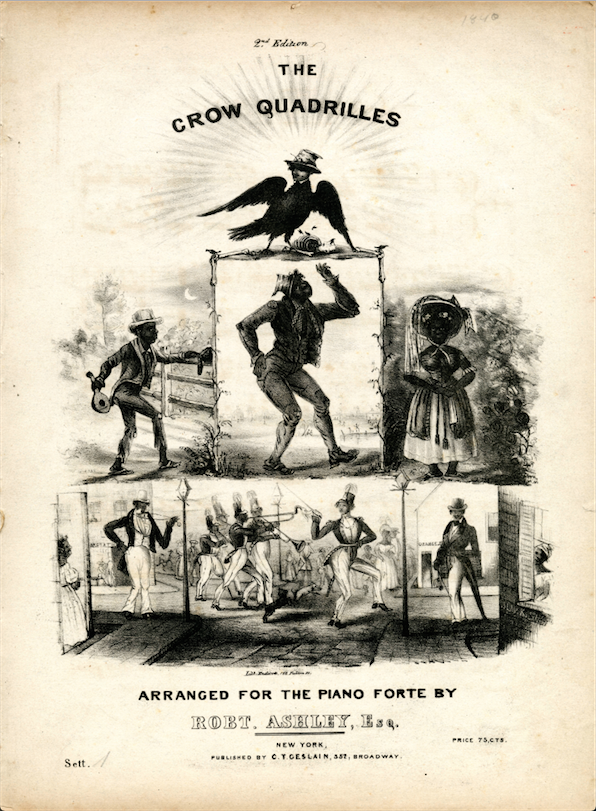

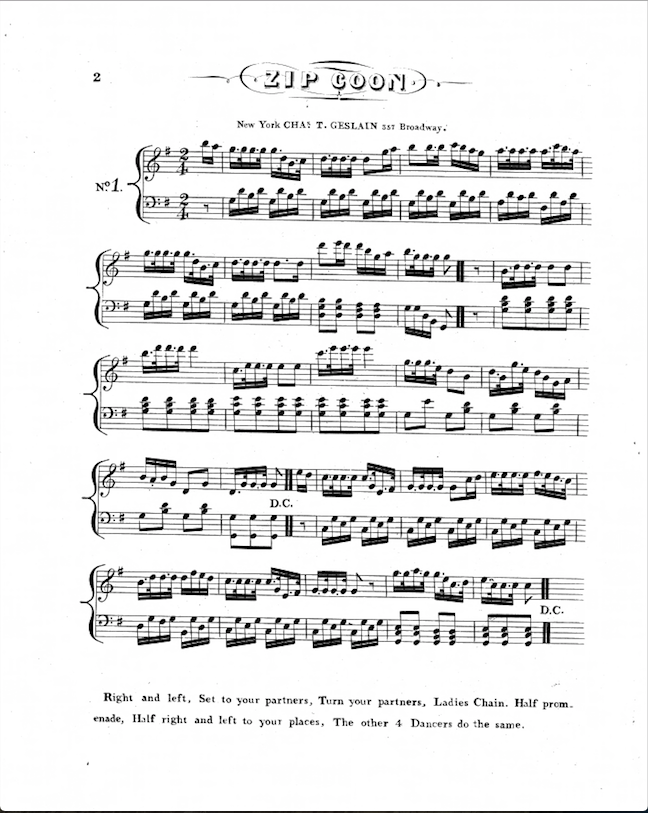

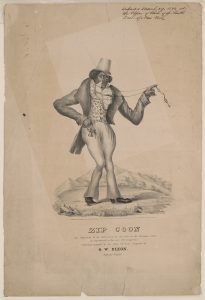

Possibly the most popular blackface caricature, Jim Crow, was created in the 1830s by Thomas Dartmouth Rice, who was known as the “Father of Minstrelsy”. The Jim Crow caricature was created to mock African slaves and to enforce the idea that they are uncultured, happy-go-lucky, and wore tattered clothing. Another popular caricature was Zip Coon, an urban African American that was frequently presented as an overdressed, slow-talking, and mischievous person. Although they lived in different environments and had different backgrounds, Jim Crow and Zip Coon were both used to depict African Americans as lazy, dim-witted people and enforce racial stereotypes.

Possibly the most popular blackface caricature, Jim Crow, was created in the 1830s by Thomas Dartmouth Rice, who was known as the “Father of Minstrelsy”. The Jim Crow caricature was created to mock African slaves and to enforce the idea that they are uncultured, happy-go-lucky, and wore tattered clothing. Another popular caricature was Zip Coon, an urban African American that was frequently presented as an overdressed, slow-talking, and mischievous person. Although they lived in different environments and had different backgrounds, Jim Crow and Zip Coon were both used to depict African Americans as lazy, dim-witted people and enforce racial stereotypes.

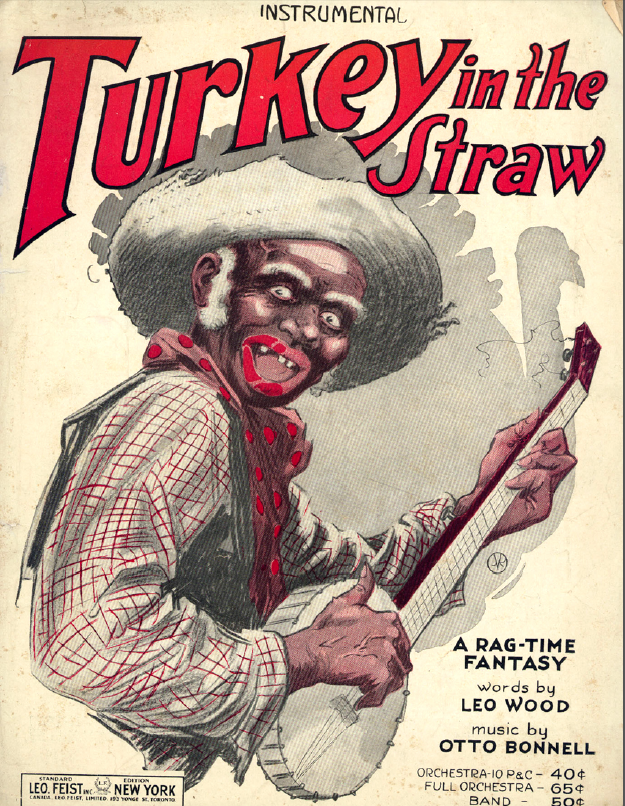

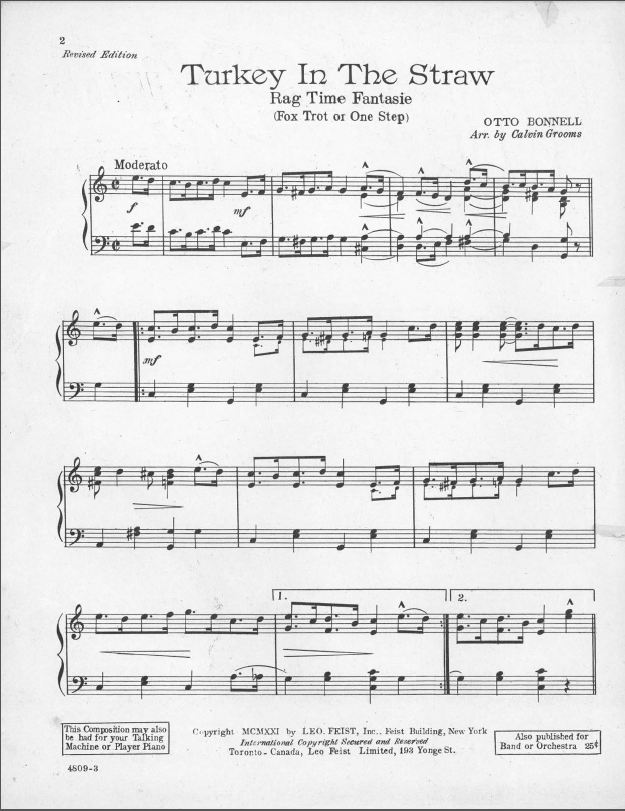

In their performances, minstrel performers would often exaggerate these stereotypes, which were already blown out of proportion, for comedic purposes. One such performer was Billy Golden, a blackface minstrel who was very active during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Golden specialized in blackface dialect comedy with some of his most famous works being “Turkey in de straw” and “Rabbit hash”. In the recordings, it’s evident that Golden is trying to imitate and exaggerate the way that African Americans would talk to enforce the idea that African Americans were uncultured and dim-witted.

In their performances, minstrel performers would often exaggerate these stereotypes, which were already blown out of proportion, for comedic purposes. One such performer was Billy Golden, a blackface minstrel who was very active during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Golden specialized in blackface dialect comedy with some of his most famous works being “Turkey in de straw” and “Rabbit hash”. In the recordings, it’s evident that Golden is trying to imitate and exaggerate the way that African Americans would talk to enforce the idea that African Americans were uncultured and dim-witted.

Caricatures and performances that mocked African Americans might have been popular among whites, however, it is not surprising that African Americans were not happy with how blackface minstrel performers were depicting them. Frederick Douglass wrote a response to blackface imitators in the North Star that called these performers filthy scum that stole African culture and used it to make a profit. Moreover, although blackface and minstrelsy don’t seem to be a big problem in modern society (short of a few exceptions every so often), the stereotypes that were ingrained in our society still seem to be very prevalent today.

References:

“Blackface: The Birth of an American Stereotype.” National Museum of African American History and Culture, 22 Nov. 2017, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/blackface-birth-american-stereotype.

Endicott & Swett, Lithographer. Zip Coon. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/00650780/>.

Golden, Billy, and Billy Golden. Rabbit Hash. 1908. Audio. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/jukebox-223095/>.

Golden, Billy. Turkey in De Straw. 1903. Audio. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/jukebox-243662/>.

Jim Crow. [London, new york & philadelphia: pub. by hodgson, 111 fleet street & turner & fisher ; between 1835 and 1845?] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2004669584/>.