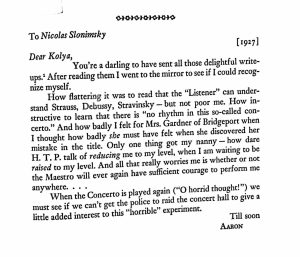

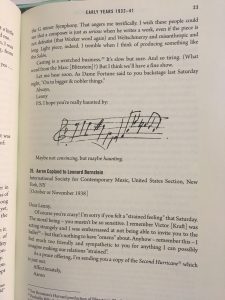

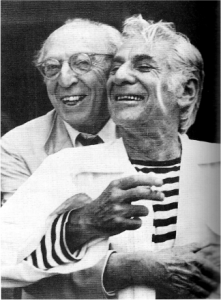

I think it is rather interesting and fun to investigate the personal lives of composers. Personally, I have never made it a habit to deep dive into the lives of composers, but I think this will become a habit soon. I’ve been looking at letters from Aaron Copland, and he is so funny! “I’m a pig! I’m a pig and a sinner and a wretch.”[1] This is the first line of the book, and it immediately displays the humanity of Copland, showing that there isn’t much difference between the performer and composer. I often experience the barrier between composer and performer, this display of humanity is refreshing.

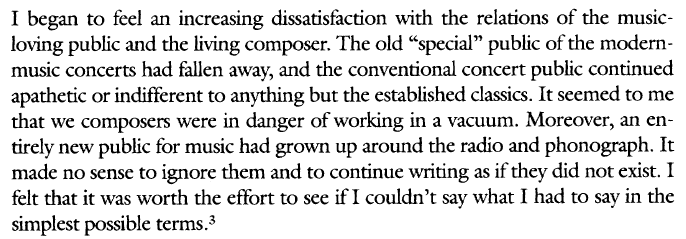

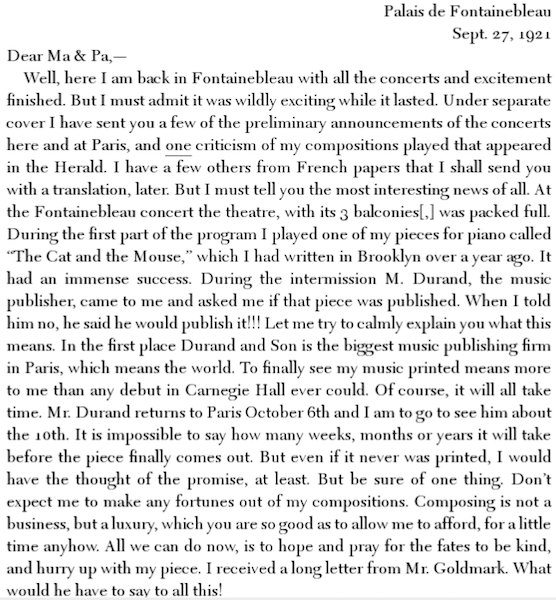

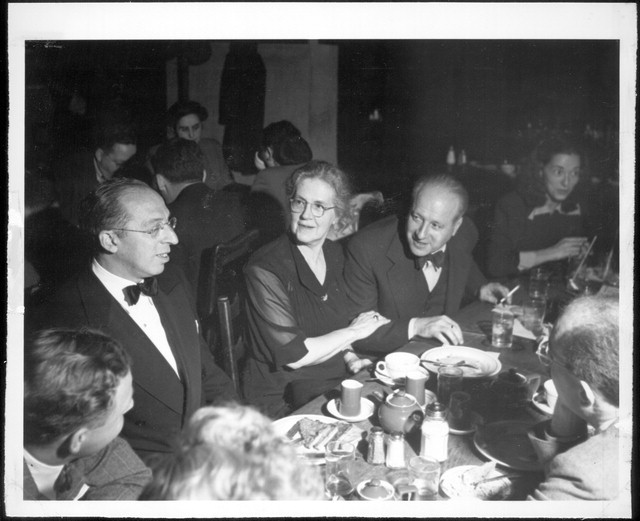

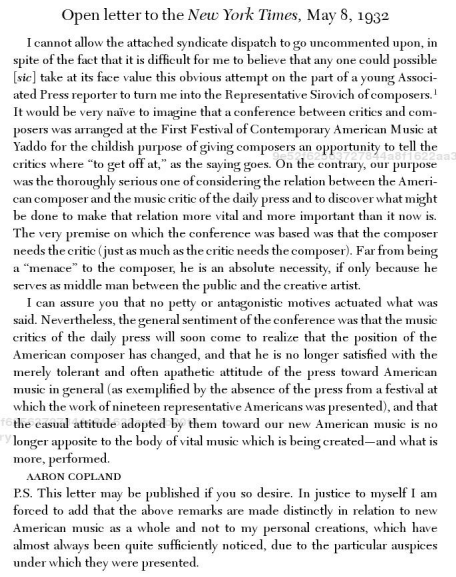

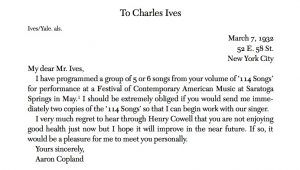

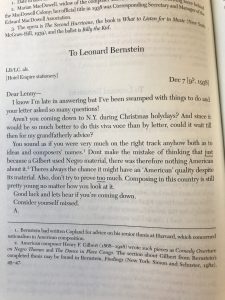

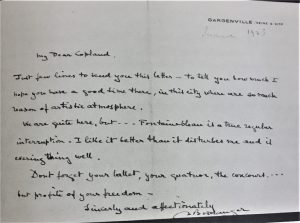

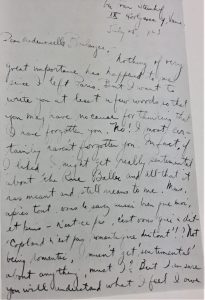

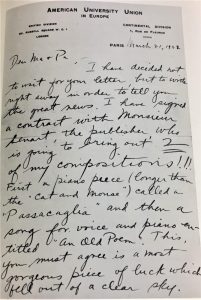

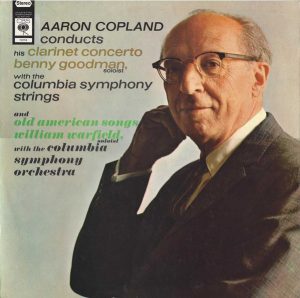

Aaron Copland has written a variety of different works, and most of them are accessible to the public. Pieces like Appalachian spring, Rodeo, and all the film music he wrote is extremely accessible. I want to take a closer look at his early life, the time that he spent in New York and Paris. When he was a teenager, he was writing letters to Aaron Schaffer, another scholar, and supposedly they discussed things like aesthetics, music, and other things. Unfortunately, the letters from Copland no longer exist, we can only infer from the letters of Schaffer.[3] Quickly after these letters, Copland applied to study in Paris the summer of 1921.[4] He writes to his parents with enthusiasm to study many different musical things when he finally crosses the sea, little did he know that he would meet the most influential person in his career, Natalie Boulanger.[5] During the infancy of his studies in Paris, Copland mostly wrote to his parents.

It is so lovely to see the enthusiasm of his writing, he is brimming with excitement being in this new country, new land, and new experiences. Copland, like many musicians, has many insecurities about his craft. I personally fall into this habit as well, of putting a composer on a pedestal and thinking that they are a genius. Taking a deeper look into these letters that Copland wrote to both his parents and others, I think is a great way of breaking these assumptions and putting the composer on the same level as the performer. They’re all people like the rest of us!

[1] Copland, Aaron. The Selected Correspondence of Aaron Copland. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006. Accessed November 5, 2023. ProQuest Ebook Central.

2 “Aaron Copland with Lukas Foss and Elliott Carter..” Grove Music Online. ; Accessed 5 Nov. 2023. https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-8000923191.

[3] Ibid

[4] Ibid

[5] Lerner, Neil. “Copland, Aaron.” Grove Music Online. 26 Mar. 2018; Accessed 5 Nov. 2023. https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-3000000119.

William Henry Jackson was tasked with exploring and surveying the American West at a time when America was expanding and the Manifest Destiny was still at the forefront of American ideology. Over his life of 99 years, Jackson became famous for his work with photochrom, such as the photo to the left from around 1900.[1] The branding of a calf is posed as a fairly leisurely activity, as a few of the characters stand around looking at their corral of cattle and the wide open space available to them in the West. Working for the government, Jackson often took exploration trips to photograph scenery along railroad routes and with his photography of beautiful natural landmarks, he even convinced Congress to create Yellowstone National Park. With photos like these, that show a decent life on the frontier and human’s domination over nature, Jackson’s narrow lens paints a Romantic image of the west, sure to keep out the fact that many Native Americans were displaced as a result.

William Henry Jackson was tasked with exploring and surveying the American West at a time when America was expanding and the Manifest Destiny was still at the forefront of American ideology. Over his life of 99 years, Jackson became famous for his work with photochrom, such as the photo to the left from around 1900.[1] The branding of a calf is posed as a fairly leisurely activity, as a few of the characters stand around looking at their corral of cattle and the wide open space available to them in the West. Working for the government, Jackson often took exploration trips to photograph scenery along railroad routes and with his photography of beautiful natural landmarks, he even convinced Congress to create Yellowstone National Park. With photos like these, that show a decent life on the frontier and human’s domination over nature, Jackson’s narrow lens paints a Romantic image of the west, sure to keep out the fact that many Native Americans were displaced as a result.