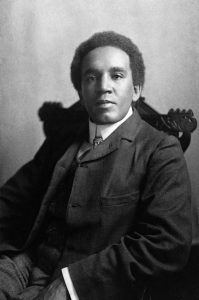

While less known today, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was a prominent and influential English composer of the early 20th century. His works were so well received in both Europe and America that New York orchestral players described him as the “Black Mahler.” Although this comment is slightly problematic, the point it makes is easily understood. His most famous work, Longfellow’s Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast, has been described as “haunting melodic phrases, bold harmonic scheme, and vivid orchestration.”

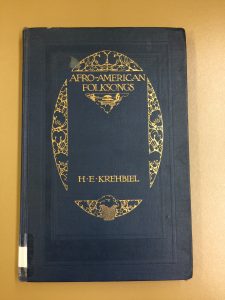

However, how does an English Composer fit in with a class focused “American Music”? In part it has to do with his collection of African melodies entitled Twenty-four negro melodies transcribed for the piano by S. Coleridge-Taylor. Op. 59. The work also includes a preface written by Booker T. Washington, a prominent American Educator and Leader in the African American Community in the early 20th century. In Washington’s Preface, he talks extensively on how much of relates back to slave music of American, and in turn, to Africa. In particular this quote stood out,

Negro music is essentially spontaneous. In Africa it sprang into life at war dance, at funerals, and at marriage festivals. Upon the African foundation the plantation songs of the South were built.

Not only does this sound very similar to jazz, but it is a spontaneous character that gave Coleridge-Taylor’s music its character.

His work, moreover, possess not only charm but distinction, the individual note. The genuineness, the depth and intensity of his feeling, coupled with his mastery of technique, spontaneity, and ability to think in his own way, explain the force of the appeal his compositions make.

While this can be applied to all of Coleridge-Taylor’s works, Washington is of course referring to the 24 melodies Transcribed for piano. Something we have talked extensively in our class has been issues with authenticity. Something unique to this book is that Coleridge-Taylor address this in his forward. Instead of maintaining their authentic forms and sounds, he states that he is simply trying to elaborate on already pretty melodies, and while doing so, he clearly states that they are not true representations of the music and do loos some of their value when being removed from their cultural context. However, again related to topics discussed in our class, he makes these transcriptions in order to elevate and celebrate African music. By treating the music in this manner, I would consider Coleridge-Taylor as American of a composer as any American-born composer.

Sources

Coleridge-Taylor, Washington, Tortolano, Washington, Booker T., and Tortolano, William. Twenty-four Negro Melodies. Da Capo Press Edition / New Introduction by William Tortolano. ed. Musicians Library (Boston, Mass.). New York: Da Capo, 1980.

Stephen Banfield and Jeremy Dibble. “Coleridge-Taylor, Samuel.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press, accessed November 16, 2017, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/06083.