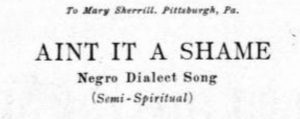

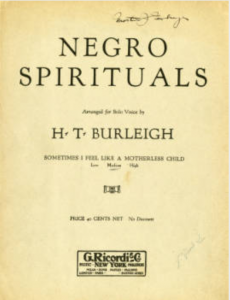

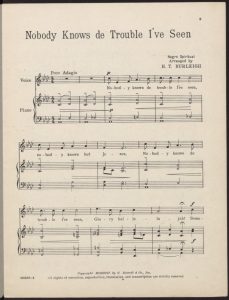

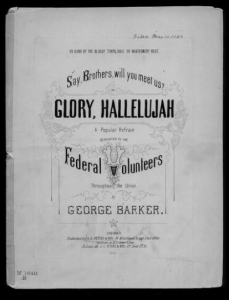

Sheet music was one of the most dominant forms of culture in the nineteenth century. Thousands of songs, pieces and concertos were sold each year. Sheet music was one of the main ways for musicians to make money at the time. However, because of the musical education needed to be able to read and understand sheet music, it created some barriers for non-white people to make money off of their art.

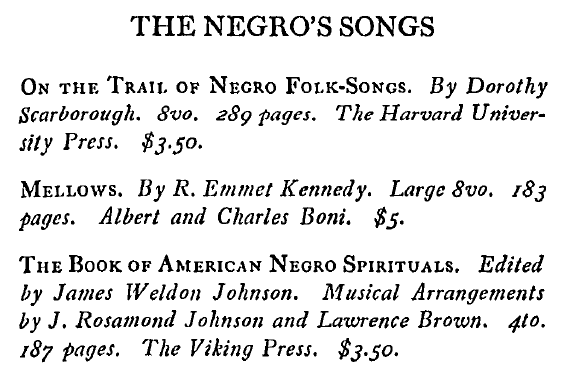

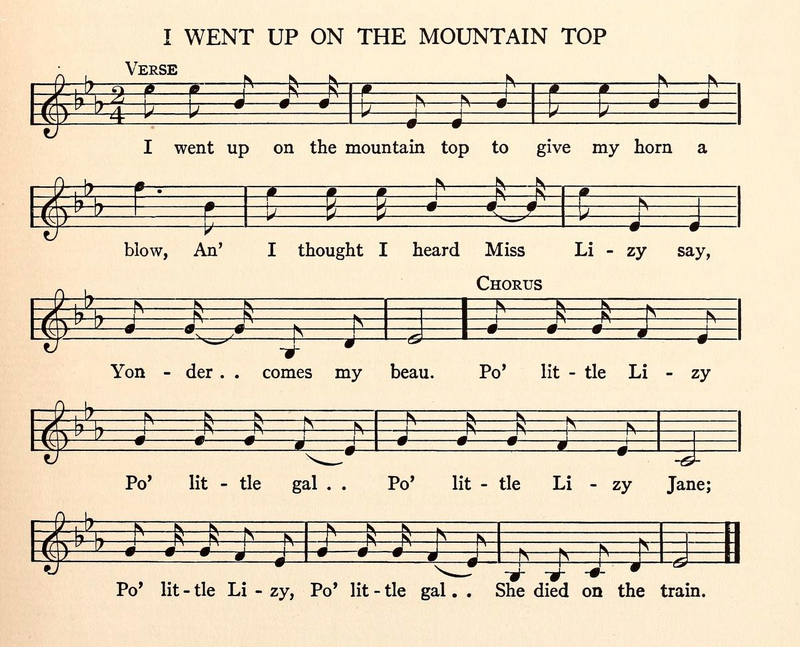

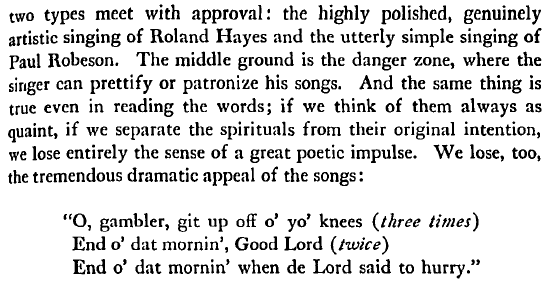

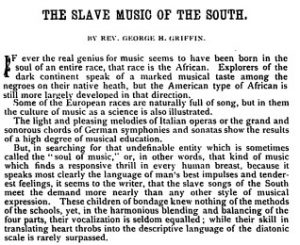

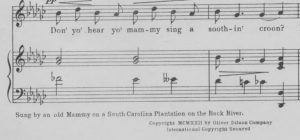

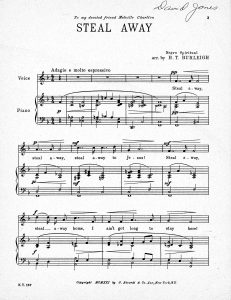

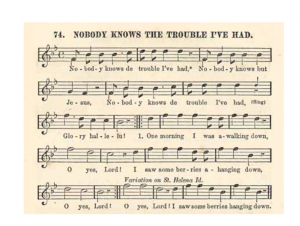

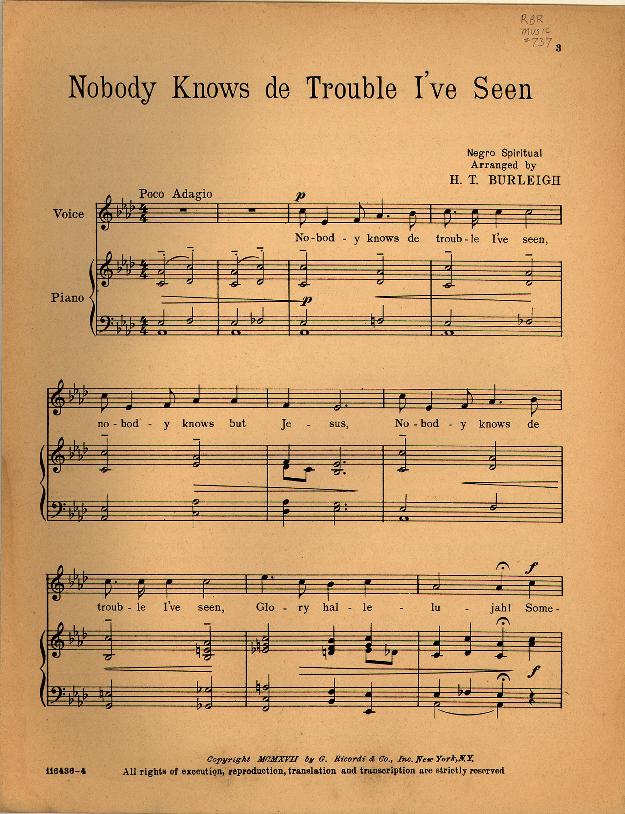

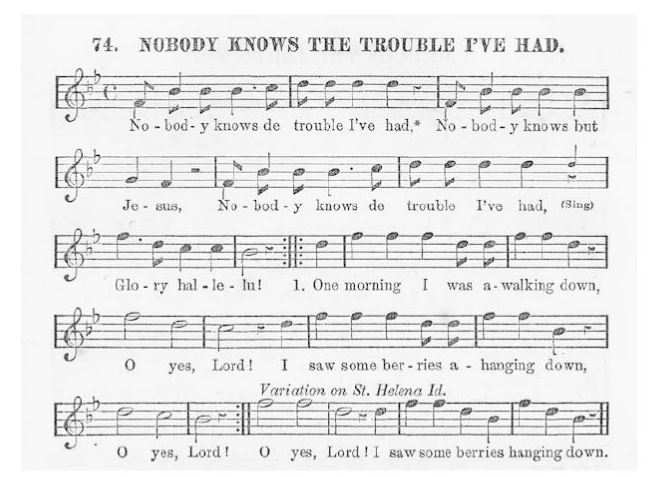

There are many popular songs written and sung today that originate from black spirituals, which were written during the time of slavery. However, unfortunately all of the musicians who wrote these songs that became so popular were not given the credit or merit or royalties from this music and instead were pushed down by white people. Because of this dark history, many black musicians were not given the credit or merit that they deserve. Unfortunately, this still happens today.

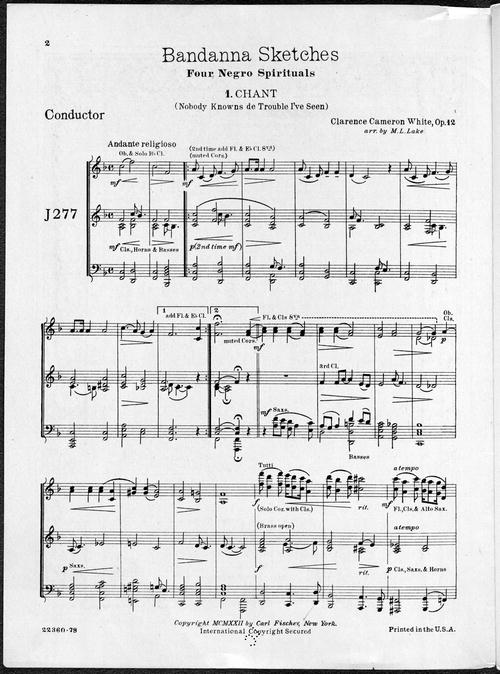

Later, post-civil war, one of the most popular form of music created by black musicians was jazz. Jazz music is either fully improvised, or a mixture of sheet music and improvisation with musicians. A melody is either given in the form of sheet music, or passed down by ear, then musicians use this melody to improvise and be creative with their instrument. Jazz often uses lead sheets as well instead of typical sheet music. This form of music was very popular in the late nineteenth-twentieth centuries. Since this music sometimes but not always had sheet music, it was difficult for musicians to gain royalties off of sheet music for jazz. However, some musicians, such as Duke Ellington composed thousands of scores and was able to make money through sheet music. Many jazz musicians made money through either touring or local performances.

Additionally, many pop musicians today create music without any prior knowledge of reading sheet music or music theory.

Although sheet music was and still is an important commodity, it is not necessary for all musicians. It is helpful to know and understand the complexities of it, however there are still great musicians who do not read music and this does not take away from any of their accomplishments in their lifetimes.

https://www.proquest.com/docview/2344508709?pq-origsite=primo&parentSessionId=ZHMRXs%2BdlljsUzJ%2BDT1X9g59so9E4BQHl4xXqDRH8uI%3D&sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals

https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvvnh25.13?searchText=&searchUri=&ab_segments=&searchKey=&refreqid=fastly-default%3Aa514c32489509c02c2a995379544e8e1&seq=1

Jackson, Maurice, and Blair A. Ruble, editors. DC Jazz : Stories of Jazz Music in Washington, DC. Georgetown University Press, 2018.

Anderson, Colin L. “Segregation, Popular Culture, and the Southern Pastoral: The Spatial and Racial Politics of American Sheet Music, 1870–1900.” The Journal of Southern History, vol. 85, no. 3, 2019, pp. 577–610, https://doi.org/10.1353/soh.2019.0163.

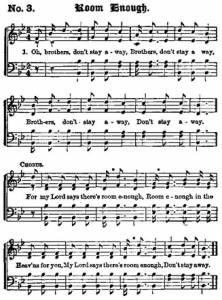

Oh, brothers, don’t stay away, . . .

Oh, brothers, don’t stay away, . . .

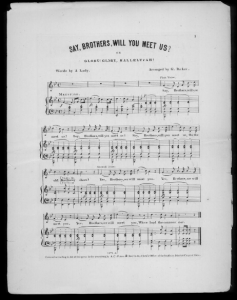

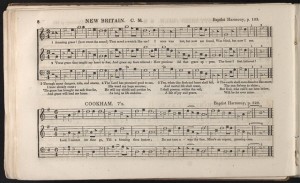

nging was mainly found in the Protestant sect of Christianity. Shape notes reinforce the importance of congregational style of singing in church, allowing for a broader inclusion of church-goers.

nging was mainly found in the Protestant sect of Christianity. Shape notes reinforce the importance of congregational style of singing in church, allowing for a broader inclusion of church-goers. The volume is composed of very beautiful melodies; and harmonies of almost unequalled richness… The tunes are admirably adapted to the effective expression of poetry, a circumstance upon which the happiest effect of Christian Psalmody depend.” A boasting review of a simple style of music, which goes to show the nature of music during this time period in America. Neither monophonic nor polyphonic, this unique style, which is heterophonic in texture, has a surprising sound that is unfamiliar, even to a trained ear. The more popular hymnody has a far more recognizable polyphonic texture that most trained and un-trained ears are accustomed to.

The volume is composed of very beautiful melodies; and harmonies of almost unequalled richness… The tunes are admirably adapted to the effective expression of poetry, a circumstance upon which the happiest effect of Christian Psalmody depend.” A boasting review of a simple style of music, which goes to show the nature of music during this time period in America. Neither monophonic nor polyphonic, this unique style, which is heterophonic in texture, has a surprising sound that is unfamiliar, even to a trained ear. The more popular hymnody has a far more recognizable polyphonic texture that most trained and un-trained ears are accustomed to.