As I am researching the Lomaxes for my final paper and for future work this spring, I took this opportunity to look through March of Time for any evidence regarding Lead Belly and his interactions with John Lomax. I was not disappointed. In a video that Professor Charles Dill calls “disturbing,” Lomax and Lead Belly “recreate” their meeting and the story of their travels together through the Northeastern United States.

The March of Time series on the whole appeared quite groundbreaking in the 30’s through 50’s, when it ran. The mini documentaries of March of Time tackled some uncomfortable topics like Nazi sentiment in Hoboken, New Jersey in 1938. Though today we might see this as a shining example of forward, positive thinking and challenging the public, the series also is a little strange – many of the videos there aren’t actual film, they are in fact recreations of events. Think of a worse version of the producers of “Survivor” re-filming the players’ dramatic moments.

The March of Time series on the whole appeared quite groundbreaking in the 30’s through 50’s, when it ran. The mini documentaries of March of Time tackled some uncomfortable topics like Nazi sentiment in Hoboken, New Jersey in 1938. Though today we might see this as a shining example of forward, positive thinking and challenging the public, the series also is a little strange – many of the videos there aren’t actual film, they are in fact recreations of events. Think of a worse version of the producers of “Survivor” re-filming the players’ dramatic moments.

The video in question regarding Lead Belly and John Lomax, titled “Leadbelly,” is a recreation of the meeting of Lead Belly and Lomax. It says that Leadbelly was released from prison (where he was being held on charges of murder) due to Lomax’s influence, and that Lead Belly was so grateful that he dedicated his life to following Lomax. In real life, however, Lomax and Lead Belly’s song for the governor had no influence on his release. The myth lives on, however.

More concerning than the false story, however, is the marketing of Lead Belly and the marketing of Lomax in the film. Lead Belly, in prison clothes, speaking of murder so openly, is a man in need of a friend. Lomax, the one who acts almost as Lead Belly’s conscience in the dialogue, appears not only as a friend, but as Lead Belly’s white savior figure. Follow this link to watch the video yourself (hopefully this will be available to embed on this page if I can get WordPress to cooperate).

This is not the only instance of the media portraying Lead Belly as a big, bad, convict. In the New York Herald, they title an article of Lomax and Lead Belly “Lomax Arrives with Lead Belly, Negro Minstrel; Sweet Singer of the Swamplands Here to do a Few Tunes Between Homicides.”

I have a lot of words to describe my reactions to that heading but I can sum all of them up with an all-encompassing “yikes.” I believe that the Lomaxes, despite whatever intentions they had to the contrary, contributed to the othering of black folk music in the way they “introduced” black folk singers like Lead Belly to the general public and made them hit sensations. I look forward to further researching this in my work this semester and this coming spring.

Here is a Lead Belly spotify playlist, for reference to his work.

For more reading on this subject, see links below:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/incomparable-legacy-of-lead-belly-180954390/

http:// search.alexanderstreet.com.ezproxy.stolaf.edu/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cvideo_work%7C1792710

https://books.google.com/books?id=YywLDAAAQBAJ&pg=PT209&lpg=PT209&dq=lead+belly+march+of+time+video&source=bl&ots=L-7hTRFsBb&sig=-2GGxoYKALizBEs9K9S77gatNHc&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiJ96qcm8LXAhVF2yYKHUyZC1gQ6AEIQTAF#v=onepage&q=lead%20belly%20march%20of%20time%20video&f=false

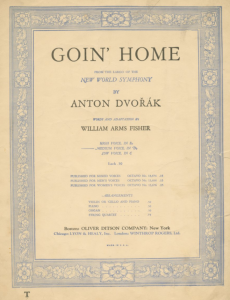

by William Arms Fisher of Anton Dvořák’s New World Symphony (No. 9, mvt II Largo, specifically). Personally, I love the symphony and have enjoyed listening to it for many years, but I can’t help but wonder now about the complicated philosophies of Dvořák and this adaptation of his work which place the work not just as a well-known music history class example to memorize, but a work that has juxtaposed good intention with possible misguided ideology.

by William Arms Fisher of Anton Dvořák’s New World Symphony (No. 9, mvt II Largo, specifically). Personally, I love the symphony and have enjoyed listening to it for many years, but I can’t help but wonder now about the complicated philosophies of Dvořák and this adaptation of his work which place the work not just as a well-known music history class example to memorize, but a work that has juxtaposed good intention with possible misguided ideology.

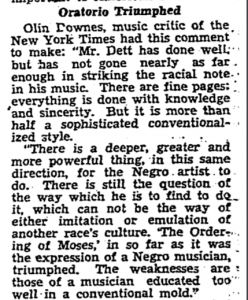

Image Courtesy of The Chicago Defender May 1937 Issue

Image Courtesy of The Chicago Defender May 1937 Issue

Eventually, Sherman Dudley’s circuit of theaters for African American performers, the “Consolidated Circuit,” merged into the Theater Owners Bookers Association (TOBA)

Eventually, Sherman Dudley’s circuit of theaters for African American performers, the “Consolidated Circuit,” merged into the Theater Owners Bookers Association (TOBA)