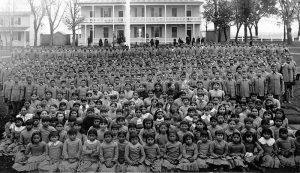

Upon decades and even centuries of reflection, scholars can debate the true motivations and implications of the cultural observation and study of Native Americans. At best, the efforts of ethnologists like Frances Densmore and James Owen Dorsey can be hailed as necessary archival work that preserved cultures on the verge of extinction from a colonialist nation. At worst, their work can be essentialized as the groundwork necessary to provide a basis for the “Vanishing Indian” discussed at length by scholar Daniel Blim and our class.

The latter is my understanding of the work of Rev. Myron Eells. In his article “Indian Music” published in an 1879 volume of The American Antiquarian: A Quarterly Journal Devoted to Early American History, Ethnology and Archaeology, the anthropologist and missionary studied many indigenous groups of the American Northwest.1 In his article, his first topic sentence immediately eases the fear of any upstanding, white American enjoying some ethnology from the safety and comfort of their log cabin: Eells assures readers the music of the American Indian is nothing complicated or culturally relevant.

“Music… consists more of a noise, as a general thing, than of melody and chords” – Rev. Myron Eells describing the music of Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest

Eells compares the musicality of the Clallam and Twana people of the Pacific Northwest. Despite detailed accounts of the percussive instruments created and the diverse use of song in the daily lives of these peoples, Eells summarizes the music as plain and dull, with little variety save for loud or soft moments. The reverend does notate the various melodies described in his prose, but his level of analysis and specificity is but a shadow of the work of Frances Densmore- a scholar discussed at length in class who will release volumes of her own works just a few decades later. Eells’ work is important in providing a sort of early “part one” to the “Vanishing Indian” condition, assuring white audiences that the music of the Native American groups he’s studied the sophistication to deserve attention beyond defining their music as simply cacophony.

To further contextualize the “Vanishing Indian”, we look to an article published The Atlanta Constitution in 1906. In this article, we are informed that an ancient relic has been preserved that upends decades of historical understanding of Native American music. The article claims a portion of the “first, genuine Indian melody” has been found. Overlooking the concerning lack of scholarly oversight in this sweeping statement, the article focuses instead on composer Abe Holzmann’s2 arrangement of this melody while in-process. After further digging, I was able to procure both a recording of a military band arrangement and a score of a piano rag arrangement of the piece.

Scan of Holzmann’s “Flying Arrow” Rag for Piano

This sheet music was found in a rag piano collection at the music library of St. Olaf College

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VxMEGT3kUac

Recording of a military band performing Holmann’s band arrangement of “Flying Arrow”

The work of ethnologists like Rev. Eells signaled to broader American society a subordination and savagery of Native Americans, which allowed composers like Abe Holzmann to create music that glorified indigenous melodies (whether truly authentic or not). By comparing these two examples, we see how the passage of time allowed for conclusions from earlier ethnologists to be realized by the musicians of the early twentieth century.