In her article entitled “The Perpetuating of Indian Art,” Natalie Curtis unveils a complicated attitude in regards to studying Native American culture. While her perspective is filled with racial biases, she does advocate for preserving Native American music in it’s most traditional and authentic form. This insistence on the importance of maintaining the original music in all its beauty is twofold: it is guided by an appreciation of the culture, but an appreciation driven by a western mindset. This mindset, shared by many scholars and white people in positions of power at the time, takes Native American culture apart in its attempts to honor and preserve what it so earnestly admires.

Natalie Curtis was an American ethnomusicologist particularly interested in preserving American Indian and African American music by transcribing songs as accurately as possible. Her work is often recognized along with the work of Alice Fletcher and Frances Densmore as an essential contribution to the preservation of a “vanishing” culture. In 1907 she published “The Indians Book,” a collection of about 200 songs transcribed principally from live performances. While that work would be thoroughly interesting to study and analyze, I have chosen to reflect on an article she wrote in 1910, which highlights a problematic approach to ethnomusicology of the time. This in no way diminishes its historical significance.

The abstract of her article is as follows:

“Those who have worked among the American Indians, and have learned to respect the thought, the art, and many of the religious ideas of this most interesting people, must feel a sense of almost personal gratitude to the present Secretary of the Interior for having appointed a Supervisor of Music in the department of Indian Education, whose duties shall be to “record native Indian music, and arrange it for use in the Indian schools.”1

If I could rewrite her thesis into my own words I would write that Indian art is beautiful and can be of use to white Americans, therefore we should preserve Indian culture instead of trying to stamp it out.

While Curtis recognizes that there are many American Indian tribes, she tends to cast large generalizations of American Indian culture in her descriptions and assertions. She refers to all Native Americans as an “underdeveloped race” and as “noble dogs.” These racially charged generalizations are contrasted with an intense attempt to exalt the beauty of the Indian music and art she witnesses, in order to spread her appreciation for this art to a larger white audience. Sharing this conflicting view of American Indians is Francis E. Leupp, whom Curtis cites in her article as the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Francis E. Leupp, in his own work entitled The Indian and his problem, asserts that westerns can know nothing of Indian culture unless they observe communities from within, but in doing so reveals gaping holes in his understanding of Indian culture. Both Curtis and Leupp demonstrate a genuine interest in Native Americans, but struggle to view it without a western scope.

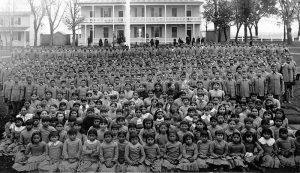

Curtis makes reference to the Carlisle Institute, the primary Indian boarding school from 1879-1918. The goal of the school was to Americanize Native Americans, and Curtis undoubtedly saw a problem with this model, shown by her critique of the governments push to destroy Indian culture. She instead believes that white teachers should encourage and inspire Indian children to learn and sing their own songs, free of western harmony and influence. Despite this honest effort to maintain American Indian culture, Curtis’ appreciation of Indian art still forces the culture to fit into her western model, as white people are the ones entrusted with preserving an art form that would disappear without the white savior.

Sources

- 1Curtis, Natalie. 1913. “THE PERPETUATING OF INDIAN ART.” Outlook (1893-1924), Nov 22, 623. https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.stolaf.edu/docview/136640521?accountid=351.

- Charles Haywood and Anne Dhu McLucas. “Curtis, Natalie.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press, accessed September 23, 2017, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/A2262178.

- Leupp, Francis Ellington. Indian and his problem. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1910. Accessed September 23, 2017. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=yale.39002003558856;view=1up;seq=2.

- Wirkkala, A. 2012. “The Art of Americanization at the Carlisle Indian School.” Choice 49 (5): 865. https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.stolaf.edu/docview/921021469?accountid=351.

- Jennifer Bess. “Casting a Spell: Acts of Cultural Continuity in Carlisle Indian Industrial School’s the Red Man and Helper.” Wicazo Sa Review 26, no. 2 (2011): 13-38. doi:10.5749/wicazosareview.26.2.0013.

- Curtis, Natalie. “A Plea for Our Native Art.” The Musical Quarterly 6, no. 2 (1920): 175-78. http://www.jstor.org/stable/737864