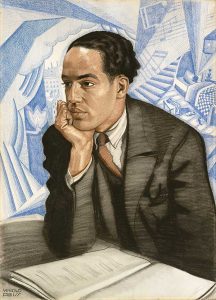

In an essay titled “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” Langston Hughes argues that the road to respect in art spaces for black Americans is not to abandon the artistic traditions and tools that belong to them in favor of the aesthetic standards of white Americans and Europeans, but rather embracing them. In making this assertion, he says “…jazz to me is one of the inherent expressions of Negro life in America…,”1 championing jazz as one of these artistic traditions to be embraced and not diminished.

Hughes’s deep love for jazz remains consistent throughout his writing, evident in a column he wrote for The Chicago Defender in July 1954. The opinion piece is titled “Hot Jazz, Cool Jazz, Deep Blues, and Songs Help Keep Life Lively,” and in it Hughes discusses his personal record collection and taste in music, particularly jazz. He begins by mentioning that “the most restful records to [him] are the ones that make the most noise.”2 Immediately, there is an informal, familiar tone which makes the reader feel like they’re having a conversation with Hughes as he shares his favorite records when he asks the reader “Do you mind?” that he loves loud music.3 He jokingly laments about how most of his records are on loan to friends and family or “accidentally cracked up,” making himself relatable and accessible to the reader before sharing his opinions.4 His love for particularly women jazz musicians such as Mae Barnes, Bessie Smith, etc. shines through in just how evenly they are represented alongside Duke Ellington and Thelonius Monk in the article.

He then moves into a defense of jazz as a wealth of education when he states “If you haven’t heard Mae Barnes sing… you need to go back to school and take up race relations.”5 He goes on and lists records he deems essential, and compares them to classic literature, implying that each jazz song holds equivalent learning to these cornerstones of the Western European canon. “Backwater Blues” contains the knowledge of the Book of Job. Ma Yancey’s “How Long, How Long” can only be substituted by the sum of Thomas Mann, Proust, Dostoyevsky, Gide, Hemingway, Tolstoy, McCullers, Ellison, and Faulkner.6 Comparing these records to texts that are widely considered to be required reading by many pretentious academics is an effective strategy, especially because each of these songs only takes a few minutes to listen to, while these books take hours and hours of time to read. Hughes’s assertion that all of that can be communicated by the language of jazz music emphasizes just how important he believed it to be.

It’s rather an interesting strategy that refers back to his perspective in “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain.” In the essay, he laments about a young black poet who had expressed that he “want[s] to be a poet–not a Negro poet.”7 Throughout the essay he discusses a greater trend that he observes where young black people are discarding black art in favor of mainstream, white, Euro-centric art and aesthetic values. He plays to the desire to conform and assimilate to whiteness by repeatedly describing individual jazz songs as more powerful than huge swaths of the European canon, calling in this opinion article on jazz for the young black people who read The Chicago Defender to treat the jazz repertoire the way they treat classic literature.

1 Langston Hughes, “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” in Keeping Time: Readings in Jazz History, ed. Robert Walser (New York ; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 56.

2 Hughes, LANGSTON. “Hot Jazz, Cool Jazz, Deep Blues, and Songs Help Keep Life Lively.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Jul 03, 1954. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/hot-jazz-cool-deep-blues-songs-help-keep-life/docview/492945618/se-2.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/silhouette-of-five-players-in-jazz-band--white-background-808891-005-59fcba5a4e4f7d001a6818a3.jpg)