Author Archives: rinckw1

Dvorak as an American Artist

In his book Dvorak and His World, Michael Beckerman provides a plethora of correspondences between Dvorak and other musicians and acquaintances. One spirit interaction is a letter written by William Smythe Babcock Matthews from Chicago on April 18th, 1893. This letter is written regarding some of Dvorak’s works, their meaning to America, as well as his connections to other musicians.

Matthews is requesting that Dvorak provide him with some details regarding what he feels towards America and music in general so that he may publish them alongside an image of Dvorak. In his letter, Matthews discusses some of the pieces he’d been listening to of Dvorak’s such as his Requiem.

Matthews describes Dvorak’s Requiem as “One of the purest musical works the Apollo club has done for years.” His admiration for Dvorak’s work is obvious, especially as he continues to praise it in context to the changing musical climate in America at the time.

In short it is a great work. Your orchestration pleased us all very much, and I was particularly gratified by the moderation of it, considering the temptation to let loose after the manner of Berlioz on the “Dies irae.”

Matthews holds great respect for Dvorak and his praise for his work in the transitional musical atmosphere of America at the time shows the importance that Dvorak held within American music. Many people wrote to him with praise and support but not many went into details regarding the climate in which Dvorak made his appearance. His music was something sublime within the times and were greatly appreciated across America, especially within those who were, as Matthews put it, “a real admirer of the composer, and a would-be friend to the man.”

“Letters from Dvořák’s American Period: A Selection of Unpublished Correspondence Received by Dvořák in the United States.” In Dvorak and His World, edited by Beckerman Michael, 192-210. Princeton University Press, 1993. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7s5r0.11.

Once Upon a Time White Folk had a Small Falling Out With Native Americans, The End.

I would like to preface this by stating any criticisms to the article are not specifically directed at the author, as I believe it is a common mistake and something that we are currently all working on more, especially within newer discussions that have emerged recently.

In searching for a topic to write about for this blog post I was searching for something relating to Native Americans, as I’ve been focusing on that topic in my blog posts. I was having trouble finding sources as each article in the Manitou Messenger only had the word a couple times and the actual focus was not Native Americans. I found the word once or twice in each article used as a supporting fact but nothing more. I was going to try to find something else to research because I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to find enough information, when I realized that the lack of information I had found was the exact thing I needed. Where were articles on Native Americans? Why weren’t they ever talked about or discussed? Why have we, as “Americans,” generally effaced Native Americans from conversation and discussion?

I eventually found an article regarding the creation of Indigenous People’s Day vs Columbus Day. This article provided some good information about the importance of this type of change, especially considering that as people become more #woke Columbus day isn’t necessarily something to be proud of. Sure, he “discovered” America, but at the same time how can something truly be “discovered” if it’s already inhabited. I expected the article to provide some insight on this, but it almost seemed as though it was skirting around the subject. It did provide a small portion of the issue by stating

The American Indian culture has been repressed since America’s origins. They were torn from the land that was theirs for centuries and forced to live on Indian Reservations. As the demand rose from white settlers, pieces of that land were taken away until the enactment of the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act.

On the other hand, while this statement is true and something we should focus on, I still feel that a 3 sentence excerpt on the issue at hand of the utter massacre of Native American’s doesn’t do the situation justice let alone respect. Massive groups weren’t simply told to move, which is an issue in itself, but were rather murdered and utterly erased from The Land of the Free. Simply skipping the fact that this happened isn’t doing anyone a favor as it’s a part of the history that we cannot ignoring. Ignoring it is almost just as sinful as disrespecting it, as it’s basically the same thing.

I found a vinyl of American Indian Music in the Southwest: Sound Recording, which provided a fascinating insight into recordings of some music that was passed down. Of course, I cannot be completely sure of the authenticity of the recordings, but it’s something that can still be studied alongside legitimate sources.

This sound recording is something that we would have possibly never been able to listen to had we completely and utterly effaced the existence of Native Americans. If we had ceased to have discussions and respectful learning, which often times it seems we are on our way to doing so, we would not have been able to learn about this culture that we mistreated so horribly in the past. Discussions like the Manitou Messenger had on Columbus Day, while it had it’s faults, are good in enlightening the folk around who are not aware of the issues. Discussion of current issues and movements as well as historical events are what we need to continue keeping our history alive. It’s not all pretty, and in fact some of it was a downright bloodbath, but we cannot pick and chose what we want to remember in our history.

Rhodes, Willard. “American Indian Music of the Southwest : Sound recording” (Folkways Records, 1951). Link

Haggstrom, Katie. “New indigenous peoples day challenges the status quo,” (Manitou Messenger, May 13 2014). Link

Romanticizing Groups of People that We Slaughtered: American Music

Once white folk had finally finished settling in American, and only after they’d properly slaughtered thousands upon thousands of Native Americans, they could truly begin defining their musical compositions. Of course, per protocol, they began this by romanticizing those that they had previously eradicated and despised. Music has long since been composed through exoticism and romanticism of the “Other,” but it is brought to a new level when that “Other” is a group that was previously massacred in the place that this new music is now being composed.

My Indian Maiden, a beautiful piece composed by Edward Coleman in New York in 1904, is a prime example of this romanticism. He presents in the title a love story between a white man and his “Indian Maiden,” who is presented on the title page of the work as an exotic beauty of incomparable standards.

Not only is this in itself problematic, but the music also holds some truly “exotic” melodies and aspects.

The piece is written in Em and even in the first bar presents stereotypically Native American musical tones. The chromatic grace notes in the top part could be associated to a war cry or horn. The rhythmic bottom line can also be tied to drums or body percussion, as it doesn’t change often and is the baseline of the music. The grace notes continue throughout the piece in the accompaniment to the melody, as well as a repeated e f g f e, highlighting the minor key and the minor third.

The lyrics portray a man venturing into a forest glade where a young Native American maiden sits outside her teepee, wearing beautiful beads and awaiting him. He then presents her with trinkets abound in riches and sings his love to her. Eventually, they will be together and all of the tribes will rejoice as they exist in harmony with nature.

Of course, these lyrics present a slightly different truth from what truly happened. Music that romanticizes the “Other” has always been present in society, but the levels to which we accept it as entertainment without either knowing the proper story or respecting that it is extremely problematic must be addressed. In children’s books, in shows, and in society as a whole, exoticism and romanticism run amuck in a disrespectful manner, and it must be addressed and discussed, else it will never be changed.

Coleman, Edward. My Indian Maiden. New York, New York: The American Advance Music Co., 1904. Link

“Spider” John Koerner

“Spider” John Koerner, a prominent blues musician, was born in Rochester, New York in 1938. He grew up in New York, and eventually found himself studying for an engineering major at the University of Minnesota. This was short lived because it was there that he met the legendary Dave “Shaker” Ray.1

Koerner’s blues career was basically jumpstarted through this encounter. The two musicians jammed together often and formed a steadfast friendship. Koerner even wrote his most famous hit, “Good Time Charlie’s Back in Town Again,” after Ray stopped in to visit him once.

While visiting Ray in New York, Koerner also met harp player Tony Glover. The three of them formed what was arguably the most well known, yet unofficial, folk trios of the 1930s2. They played many gigs together, always providing a great time for their audiences as well as themselves.

Dave and Tony were kind of livin’ in Minneapolis cause that was home to them and they had things holdin’ ’em there. I had the chance to travel and I could get the work so I started travelin’ around. Then we’d just meet whenever we were in the same town together and play jobs whenever anybody was willin’ to put us together.3 ~Koerner

Their performances were well known to be enjoyable for both the audience and the performers. Koerner always made it a good time for everybody, and it was well appreciated by all those who saw and knew him. One of the last times the group got together was a prime example of this.

It was kind of weird. We played the Tyrone Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis. We played one night opposite the Who. We were very drunk and fairly well stoned and we had practiced together just a couple of hours. It was kind of shakey but we had a good time.4 ~Koerner

In his solo performances, Ray’s influence in his life could also be seen clearly. When he performed at the Quiet Knight in December 1968, he was introduced as having been influenced by Ray from a young age.5 He grew up listening to him from a young age, and this transitioned into his own playing. Another time, when he returned to perform at the Gaslight, his audience “remembered” and requested that he play “Good Time Charlie’s Back in Town Again” which he wrote for Ray. When describing his performance, Koerner said…

Tony Glover calls it the oatmeal shake, cause it looked like you dipped your hand in a bucket of oatmeal and tryin’ to get it off by shakin’ your hand6 around. ~Koerner

Koerner was an amazing performer who had both talent as well as a charismatic and fun presence. He was greatly influenced by Dave Ray, as well as Tony Glover. Ray’s influence especially could be seen throughout his entire life, and it goes to show you how a simple chance encounter can truly go a long way. Koerner never expected success to find him when he was planning on becoming an engineer, but it did just that.

1 Joe Klee. “Spider John’s Back in Town.” Rock, January 3, 1972 (henceforth Klee).

Klee, Joe. “Spider John’s Back in Town.” Rock, January 3, 1972. http://www.rockandroll.amdigital.co.uk.ezproxy.stolaf.edu/Contents/ImageViewer.aspx?imageid=988853&pi=1&prevpos=905675&vpath=searchresults

Chicago Daily Defender, “Quiet Knight Presents the Blues.” Chicago Daily Defender, December 31, 1968. https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.stolaf.edu/hnpchicagodefender/docview/494406297/B715397467854A86PQ/1?accountid=351

Music History and the Importance of “History”

From Bach to Beethoven to Mozart to Haydn, we learn many of music’s prominent historical figures in our music history courses. At the same time, we don’t hear some names such as Beach, Farrenc, or Lateef. In fact, some probably don’t know who any of the names I just mentioned are! It’s blatantly obvious that in learning about music history, there are many composers and musicians that we don’t touch on, and even more that we just don’t have the opportunity to learn about. It’s important to always expand on the knowledge we gain, and realize that there are infinite topics to cover, even if we don’t hear about them in a textbook.

One example would be instruments. One instrument that we don’t hear about today, but that is still fascinating is the Ocarina. More specifically, it’s ancestor the Xun. In this recording, the airy instrument we hear is the Xun, played by Yusef Lateef.1 The Xun is an aerophone that was created in China approximately seven thousand years ago. It is similar to the ocarina, without the flippant mouthpiece.2

This instrument is similar to the more well known relationship between the flute and the piccolo for example. While one instrument may seem more normal or be more well known, the other is just as important and still within the family of the first instrument. It’s fascinating to study both of them, and an example of something worth studying.

In Yusef Lateef’s autobiography, he touches on the importance of listening to multiple accounts regarding the origins of instruments and music itself. When discussing the origins of some jazz music and a group of white musicians, he states that “because they were among the first to be recorded it followed that they would be considered the inventors of the music. Nothing could be farther from the truth.”3

Yusef himself was an accomplished musician, and someone that we don’t learn about today. In newspaper articles, people referred to him as an “outstanding multi-reed man”4 with an “amazing certainty as a bass soloist.”5 They said his performances “take you on a specialized trip.”6 He was an extremely accomplished musician who was known to many, but not known by all.

It’s inconceivable that everyone learn everything about music history, but these are a couple examples of the broad world that is encompassed by music. The Xun is a beautiful sounding instrument, especially when played by such a talented and accomplished musician such as Yusef Lateef. For most of us, this instrument and performer were beforehand unknown to us, but with some time and research, fascinating and new things can be learned, and our knowledge can be broadened.

2 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xun_(instrument)

4 “The Diverse Yusef Lateef.” Soul, April 6, 1970.

5 “Music Whirl.” Tone, October 1, 1960.

6 “Yusef Lateef’s Detroit.” Soul, June 30, 1969.

“Music Whirl.” Tone, October 1, 1960.

“The Diverse Yusef Lateef.” Soul, April 6, 1970.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xun_(instrument)

“Yusef Lateef’s Detroit.” Soul, June 30, 1969.

Yusef Lateef: Eastern Sounds, composed by Yusef Lateef, 1920-; performed by Yusef Lateef, 1920-, Barry Harris, 1929-, Ernie Farrow and Lex Humphries, 1936-1994 (Prestige, 1991), 40 mins, 9 page(s)

Yusef Lateef, “The Gentle Giant: The Autobiography of Yusef Lateef.” (Irvington, NJ. Morton Books Inc. 2006. Pages 2-3.

The Importance of the Preservation of Children’s Singing Games

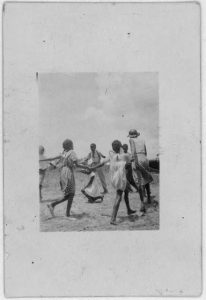

While looking at my of the photos on in the Lomax Collection, I was drawn to some photos of children who were playing singing games near Eatonville, Florida in 1935.1 I was curious not only about these games, but about what music was sung, and in what situations these specific games were played. Unfortunately, I can already tell those who are reading this that I had immense trouble finding answers to these questions, and instead am simply going to be drawing connections between the photographs of these events, and the broader importance of the maintaining of music in children’s lives.

The photographs that I observed were taken of a group of children playing singing games. These photos included one of a girl who was a soloist, as well as the children dancing around, holding hands, and going in a circle.2 In one of the photos, writer Zora Neale Hurston is seen dancing with the children, and experiencing it for herself instead of simply documenting it and moving on.3

These photographs and the interviews that were performed with those associated were made possible through new technology, and the advancement of humanity’s capability of remembering and documenting through recordings and photography. In fact, one recording begins with

“Dear Lord, this is Eartha White talkin’ to you again. I just want to thank you for giving mankind the intelligence to make such a marvelous machine [the portable recorder], and a president like Franklin D. Roosevelt who cares about preserving the songs people sing.”4

It is thanks to this kind of technology that we can preserve these kinds of songs and dances, and the games and fun associated with them. It also allows a continued study of the importance it held, perhaps not even in a specifically cultural context, but to those, such as the children in the photos, who enjoyed the music for what it was.

At the same time, it is advancements in technology that give me cause to worry. As a kid, I remember music played an important role in my life through games outside with friends where we would sing London Bridge and then fall into a heap giggling at the end of the song, or Ring Around the Rosy in the park. Nowadays, kids are playing video games and using technology to have fun, instead of the good old music. Now, I’m not here to preach against video games or specific age limits to which we should introduce our kids to these types of new technologies, but instead I’m here to touch on the importance of at least remembering the past, and the different ways in which people entertained themselves.

As we’ve learned in our courses, music tells a story not only about the composers and musicians performing the pieces, but also of those who listen to it. Music connects us to our emotions, whether we be children or adults, and our tastes are affected by our states of existence and being. As children, this is the same, and the preservation of these experiences – children playing singing games – through photos and recordings helps us understand our ancestors, as well as just differing ways of life due to the passage of time. Preserving these events in our daily lives is something I believe to be important, just as it will likely be important to preserve how children entertain themselves nowadays, whether or not we agree or disagree with it, because it’s defining of the times we live in.

Lomax, Alan. African American children playing singing games, Eatonville, Florida. June, 1935. Lomax Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs. Accessed October 2, 2017. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/lomax/item/2007660109/

Lomax, Alan. African American children playing singing games, Eatonville, Florida. June, 1935. Lomax Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs. Accessed October 2, 2017. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/lomax/item/2007660110/

NPR. The Sound of 1930s Florida Folk Life. February 28, 2002. Black History Month, NPR. Accessed October 2, 2017. http://www.npr.org/programs/atc/features/2002/feb/wpa_florida/020228.wpa_florida.html

Understanding and Respect: The Nez Percés

One of the most discussed topics regarding the traditions and beliefs of other cultures and other people outside of western traditions is that of how one can attempt to understand and learn of them, without stepping into the realm of appropriation. This discussion, reflected in our class discussions on the differences between cultural sharing and cultural appropriation, is one that must be discussed, else there are consequences. As someone whose heritage lies in the Nez-Percés tribes of old in Idaho, I often question how much I can delve into the traditions without stepping on the toes of those who came before me. As someone raised in a white household, being brought up on French traditions, I do not know enough of the traditions of my ancestors, yet I have always been raised with the utmost respect for them. This respect is what leads me to crave knowledge in learning more regarding my heritage, yet it’s important to understand that I will never truly understand the traditions and beliefs of the Nez-Percés, as one cannot truly understand without being born and raised in the culture.

Cultural Misunderstandings

There are many types of cultural misunderstandings, two of which that I will discuss in this post being that of malicious cultural misunderstanding compared to ignorant cultural misunderstanding. In regards to the Nez-Percés, the first type of misunderstanding was what they encountered initially with white folk. One document I looked into was a recount written by a white man named Lawrence Kip, who was with the Escort from the 4th Infantry, regarding the 1855 Indian Council.1 What I focused on primarily in the recount was his descriptions of the Nez-Percés tribe before and throughout the council. In his first encounter with the Nez-Percés, he refers to it as his “first specimen” of the Nez-Percés.2 This initial vocabulary, in referring to the approaching tribe as the first “specimen” he encountered already places them below the white man. Without any experience with the tribe, he has already assumed them to be inferior beings to himself, and this will continue throughout his experience with the tribe, as it did in the minds of many other white men.

In continuing his description of the natives he encountered, the western world’s infatuation with the exotic was also portrayed. He described them in a majestic light, claiming that they assumed the grace of centaurs, being one with their steeds. They were “gaudily painted,” had “fantastic embellishments flaunted in the sunshine,” and had “fantastic figures” covering their bodies. In the end, he wrapped up his initial description as “wild and fantastic.”3 To him, they were wild savages, yet they were fascinating, fantastic, and something utterly exotic from what he’d experienced before.

The Nez-Percés were known to be one of the kindest tribes to the white men, yet while visiting one of the Nez-Percés chiefs, Kip lumped them and their enemies, the Blackfoot tribe, together as savages.4 The lack of distinction between two tribes, one seemingly more violent to the white men than the other, shows the lack of care and thought that the white folk gave the tribes, no matter how kind.

It has been greatly discussed that the musical accomplishments of native americans stray from those in western culture, although that does not in any way diminish their music. Pitches and rhythms that are not in the western music cannot be dismissed as lesser, or incorrect, but must rather be adopted, as they are all music. Kip described their musical instruments as of the “rudest kind,” their singing as “harsh,” and overall “utterly discordant.”5 Even one who was not adept in music couldn’t find a way to appreciate what he heard, and instead described it in the words that we don’t dare use to describe music. While something may be discordant, it is still appreciated in western culture, unless, it seems, it is a part of another culture altogether, in which case it is dismissed as something that is not music, and something we cannot appreciate in the same manner.

Kip’s description of his experience with the Nez-Percés tribe is not to be taken as a factual and perfect account, as he had his biases. It is important to search other references, as I shall continue to do so in later blog posts. This original conception of the Nez-Percés tribe was something that was later to bring on the Nez-Percés Campaign, where the white men went to war with the tribe. This misunderstanding and refusal to understand other cultures was what brought on violence, and is what I’m referring to as a malicious misunderstanding. While it was not explicitly malicious to begin with, the fact that the newcomers found the native american tribes to be inferior to them was the beginning of homicide. What could be considered a misunderstanding was not solved in an equal and understanding manner, therefore there was no resolution.

Nez-Percés Campaign

Another very interesting document that I found was a map of the Nez-Percés Campaign. It depicts the path taken by the newcomers in their war against the Nez-Percés, as well as drawings of fighting grounds, military movements, and notes of times and dates when specific events occurred.6 It is the prime example of the consequences that can happen from cultural misunderstanding and more specifically, the lack of respect and attempt for peace with other cultures.

Nez-Percés Traditions and Religions

The second misunderstanding I’m going to discuss occurs often in today’s world, and is something I’m experiencing currently when researching the Nez-Percés. I am aware that for all of the research I can do, I can only gain a small glimpse into the truth regarding the culture of the Nez-Percés, and I cannot hope to truly understand their culture and traditions. At the same time, in my attempts to research it I hope to gain more insight on something that is both important to me, and should be important to everyone else out there, as it is important to learn and respect other cultures.

In R. L. Packard’s “Notes on the Mythology and Religion of the Nez-Percés,” he goes into detail of first hand accounts of a very small amount of traditions of the Nez-Percés. He gets his information in a discussion with James Reubens, who is a member of the Nez-Percés tribe. Even at the beginning of the conversation, the concept of misunderstanding and lack of respect in learning as portrayed in Reubens’s statement that he was worried Packard only had the “idle curiosity of a white man,”7 rather than a true passion for learning and respecting Nez-Percés traditions. This statement is a prime example of the issue at hand, where people are ignorant of the cultures they are stepping on and appropriating, yet make no attempts to learn about them in depth. Sometimes, it is due to pure ignorance, as they do not know that there is an issue, but other times it is due to laziness, which is something else altogether that we must combat.

As Reuben continued to discuss Nez-Percés traditions and beliefs, he touched on another prominent barrier in true understanding. He said that “the way we (the Nez-Percés) get our names is a beautiful thing when told in our language, but I cannot tell it well in English.”8 The language barrier that exists is extremely inhibiting, yet unavoidable. Without knowledge of the language and time spent with the culture, one cannot hope to gain true understanding of it. At the same time, this is another reason people are unwilling to learn, and wish to simply continue living their lives in an ignorant manner.

One tradition that was extremely interesting to learn about was the tradition of how children received their names in Nez-Percés culture. I do not dare to paraphrase the process, as it is complex and deserving of a true description. Even now, I am using a paraphrasing that Packard received in his discussion with Reubens.

“When a child is ten or twelve years old, his parents send him out alone into the mountains to fast and watch for something to appear to him in a dream and give him a name. His success is regarded as an omen, and affects his future character to some extent. If he has a vision, and in the vision a name is given him, he will excel in bravery, wisdom, or skill in hunting, and the like. If not, he will probably remain a mere nobody. Not to every child [boy or girl] is it given to receive this afflatus. Only those serious-minded ones, who keep their thoughts steadfastly on the object of their mission, will succeed. The boy who is frivolous, who allows his attention to be distracted by common objects on his way to the place of vigil, or who while there succumbs to homesickness, or gives himself up to the thoughts about hunting in the woods he has passed, or fishing in the streams he has crossed, will probably fail in his undertaking. On reaching the mountaintop, the watcher makes a pile of stones three or four feet high as a monument, and sits down by it to await the revelation. After some time – it may be three or four days – he “falls asleep,” and then, if fortunate, is visited by the image of the thing which is to bestow upon him his name and the wisdom and power belonging to it.”9

Why does this matter to me?

One thing in particular rang with me in reading this description, and that was the line “the watcher makes a pile of stones three or four feet high as a monument”10 atop the mountains. Towards the end of the section, Packard mentions that “there are many of these little monuments referred to on the mountains of Idaho.” Growing up, I often came across these monuments, as did others, but people simply believed they were put there by others hikers, and added their own stones to the piles. I did the same. Never once did it occur to me that the piles of stones were monuments to something more important, something that I should have been respecting throughout my entire childhood.

Why does this matter to anyone?

In learning about one simple tradition, I gained a deeper understanding and respect for the culture, and it is something that I will spread to all those who I am with when I run into these monuments. I believe that it is important to take the time to learn about other cultures, and it is important to learn to respect them. Objects such as the first hand accounts regarding some old white man’s first experience with the Nez-Percés tribe, albeit biased, is something that we must study in order to understand past mistakes, and in order to never make them again. Maps of conquests, while violent, are something that we must view in order to understand the occurrences and events that formed the present. First hand accounts are something that we must listen to, and something that we must always respect, especially when they are difficult to share. While we cannot truly understand, we must make an effort in order to avoid the mistakes of our predecessors and ancestors. Through research, discussion, and open-mindedness to learn, we must work to understand and respect everyone.

6 Oliver Otis Howard and Rob H. Fletcher, “Map of the Nez Perce Indian Campaign.” (1878)

Howard, Oliver Otis (1830-1909); Rob H. Fletcher. 1878. Map of the Nez Perce Indian campaign. Available through: Adam Matthew, Marlborough, American West, http://www.americanwest.amdigital.co.uk/Documents/Details/Map_6F_G4241_S55_1878_F5 [Accessed September 26, 2017].

Kip, Lawrence. 1855. The Indian Council in the valley of the Walla-Walla. 1855. Available through: Adam Matthew, Marlborough, American West, http://www.americanwest.amdigital.co.uk/Documents/Details/Graff_2342 [Accessed September 26, 2017].

Packard, R. L. “Notes on the Mythology and Religion of the Nez Perces.” The Journal of American Folklore 4, no. 15 (1891): 327-30. http://www.jstor.org/stable/533388?origin=crossref.