Wampum is a traditional shell bead of the Native American tribes of the Eastern Woodlands. The beads are harvested from the shells of Western North Atlantic hard-shelled clams and are typically white and purple. Native Americans would harvest the clams in the summer and eat their contents before working on the shells. The process of creating wampum was long and hard, usually taking a full day to make just one bead. Shells would be ground or drilled down very carefully using rocks. Not only was the process difficult, but it was also somewhat dangerous, fine dust from the shaved off shells could cut up the lungs if ingested so Native Americans would often use water to limit the dust.

After the beads were made, they were placed on strings made of either plant fibers or animal tendons. They were often worn decoratively and sometimes even formed into belts which were used to tell stories and mark agreements between peoples. There were usually only two colors of wampum, white and purple, each having their own meanings. White wampum usually denoted purity or light while purple wampum typically represented war, grieving, and death. The two colors would often be combined to represent the duality of the world.

Wampum strings and belts had many uses such as currency, gifts, and a means of telling stories. Tribes would often trade wampum with each other in exchange for other goods. Due to the meaning of each color of bead, wampum was also used as a gift, white wampum being given to celebrate things like births or marriages and purple wampum being used for condolences after the loss of loved ones. Moreover, mixed belts, which represented the duality of the world, were given as peace treaties and used to tell stories to others and future generations.

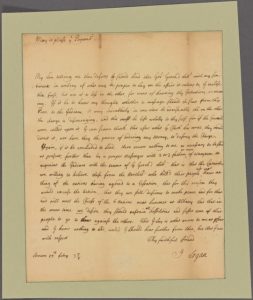

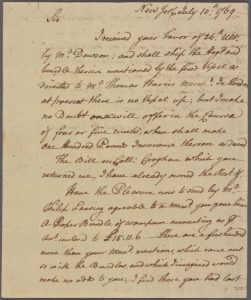

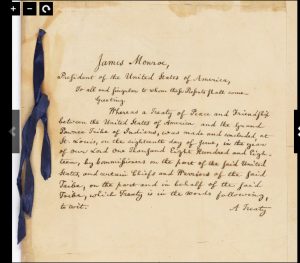

The worth of wampum was also recognized by many European settlers. A letter written to Thomas Penn from James Logan in 1937 shows that the Europeans knew the significance of wampum. In a proposal to meet the chiefs of the Six Nations at Albany, Logan proposed that Governor Gooche accompany his letter with 2 to 3 fathoms of wampum as a peace offering. Wampum beads and belts even became a commodity in Europe. In a receipt written from Isaac Low in 1769, a paper bundle of wampum was sold to someone in Europe for £15 11s. 6d.

Although the significance of wampum has dwindled for non-Native Americans, wampum and the process of making it is still unquestionably important to the culture and traditions of Native Americans. This video shows the traditional process of making wampum by hand, still followed by Native Americans today.

References:

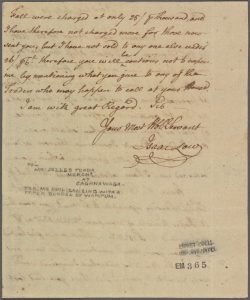

Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. “Letter to [Jelles Fonda, Caghnawaga]” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/b8a373ad-28d8-942d-e040-e00a18065263

Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. “Letter to the Proprietary [Thomas Penn]” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/bb4ebb8a-0e86-c85e-e040-e00a18063bc4

Scott Dressel-Martin. Wampum belt. 7/26/2010. Retrieved from the Digital Public Library of America, https://dmns.lunaimaging.com/luna/servlet/detail/DMNSDMS~4~4~11333~100798. (Accessed September 20, 2022.)

Traditional Wampum Belts. PBS. Public Broadcasting Service, 2018. https://www.pbs.org/video/traditional-wampum-belts-gy05in/.

Tweedy, Ann C. “From Beads to Bounty: How Wampum Became America’s First Currency-and Lost Its Power.” ICT. ICT, October 5, 2017. https://indiancountrytoday.com/archive/from-beads-to-bounty-how-wampum-became-americas-first-currencyand-lost-its-power.

Tweedy, Ann C. “From Beads to Bounty: How Wampum Became America’s First Currency-and Lost Its Power.” ICT. ICT, October 5, 2017. https://indiancountrytoday.com/archive/from-beads-to-bounty-how-wampum-became-americas-first-currencyand-lost-its-power.

Wallace, Anthony F C. “The Iroquois Wampum Belts.” Anthropology News (Arlington, Va.) 12, 4 (1971): 7–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/an.1971.12.4.7.2.

Wampum Belt. 1682. Retrieved from the Digital Public Library of America, https://dlgadmin.galileo.usg.edu/iiif/2/dlg%2Fguan-dpla%2Fartsus%2Fguan-dpla_artsus_in26%2Fguan-dpla_artsus_in26-00001.jp2/full/1000,/0/default.jpg. (Accessed September 20, 2022.)

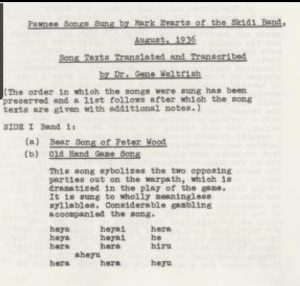

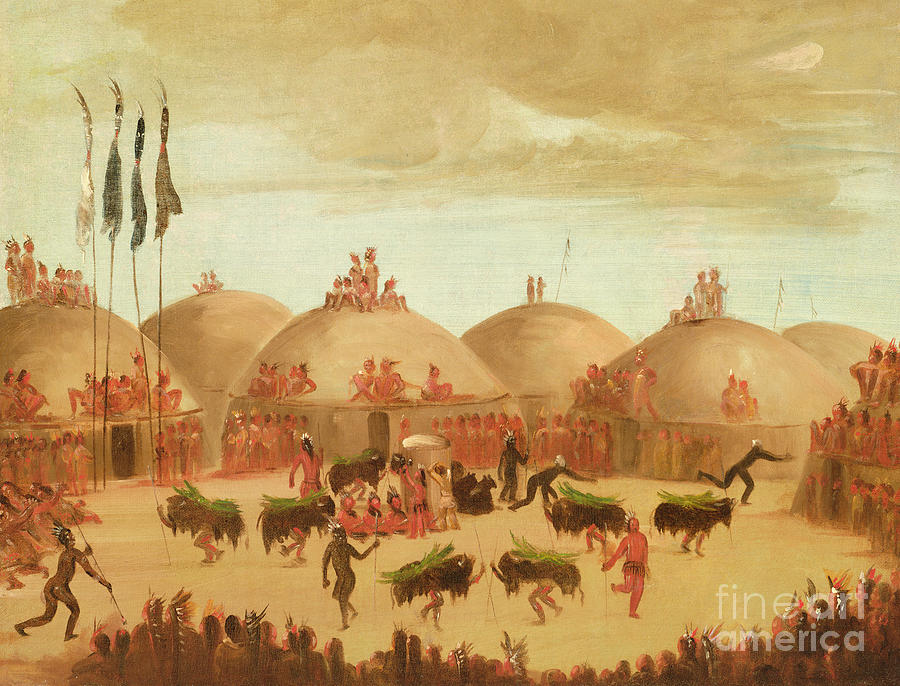

Catlin mentions that large water-filled sacks were used as drums, along with rattles, to accompany a song which is repeated many times throughout the ritual, and notes that it was impossible to obtain a translation of this song, as it was a closely guarded secret even within the tribe. However, beyond these observations he makes no attempt to analyze the lyrics, composition, or instrumentation of the song, focusing instead on the visual spectacle of the bull-dance, which he describes as being “of an exceedingly grotesque and amusing character”.

Catlin mentions that large water-filled sacks were used as drums, along with rattles, to accompany a song which is repeated many times throughout the ritual, and notes that it was impossible to obtain a translation of this song, as it was a closely guarded secret even within the tribe. However, beyond these observations he makes no attempt to analyze the lyrics, composition, or instrumentation of the song, focusing instead on the visual spectacle of the bull-dance, which he describes as being “of an exceedingly grotesque and amusing character”.