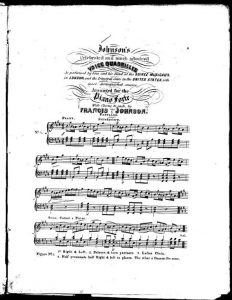

The manager of the Baltimore Museum bought an advertisement in the Baltimore Patriot on November 4th, 1831, to publicize an upcoming event, shedding light on the role of music in antebellum American society. The manager wished to advertise an exhibition that would be occurring at the museum that Saturday night at which Francis Johnson and his military band would be performing, in order that “amatures [sic] and connoisseurs in fine painting” alike would be able to enjoy “the concord of sweet sounds” of the live music.1

This advertisement reveals several details about the role of music, and art in general, in American society in the early nineteenth century. At the time, bands like Johnson’s could not distribute their music by recording. Instead, their profits came from performing live. While many ensembles, especially Johnson’s band, put on their own concerts, this article demonstrates that they also performed at events that were not necessarily dedicated concerts but simply required some musical accompaniment. Music could be combined with the experience of viewing paintings for the greater enjoyment of “amatures and connoisseurs” alike, indicating that while this was a social function, it was more about the sensory experience than about asserting the upper class identity of those who had the luxury to consider themselves “connoisseurs”. This was the same tradition of live performance that minstrel shows and vaudeville would evolve from, and the combination of different forms of entertainment in one event for convenience and accessibility actually resembles these later traditions.2 The manager of the museum describes Johnson and his band as “famous” and “excellent” and advertises that they would “perform many of the most popular and justly celebrated pieces of instrumental music”, which was a feature of much of the American concert music of the early nineteenth century. Bands and even early American orchestras would mix high-brow music with more popular and fashionable music, drawing very diverse crowds as a result.3 However, money was still a factor for the artists, and just as Johnson’s band relied on public support, the success of this museum was “so much indebted to the liberal patronage” of the public.1

By playing popular music at public events like this art exhibition in addition to their own concerts, ensembles like Johnson’s band could draw audiences from a variety of backgrounds, garnering attention for their music as well as for the art displayed at the museum. Their reliance on public support helped both institutions–that of music and that of art museums–to reach a wider audience, ultimately creating more opportunities to engage with art and in turn contributing to more widespread artistic literacy among the American public.

References:

1 “Advertisement.” BALTIMORE PATRIOT & MERCANTILE ADVERTISER. (Baltimore, Maryland) XXXVIII, no. 98, November 4, 1831: [3]. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&docref=image/v2%3A107D4AD8C258B928%40EANX-108270873A425650%402390126-10827087F7BAA9A0%402-1082708C24416710%40Advertisement.

2 Lewis, Robert M., ed. From Traveling Show to Vaudeville : Theatrical Spectacle in America, 1830-1910. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003. Accessed November 25, 2022. ProQuest Ebook Central.

3 Locke, Ralph P. “Music Lovers, Patrons, and the ‘Sacralization’ of Culture in America.” 19th-Century Music 17, no. 2 (1993): 149–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/746331.

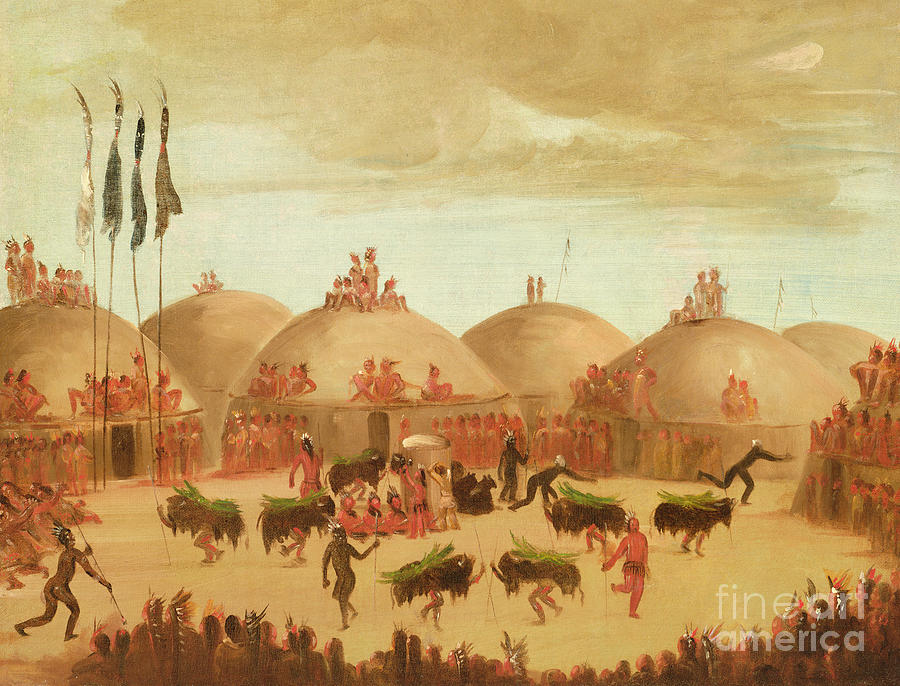

Catlin mentions that large water-filled sacks were used as drums, along with rattles, to accompany a song which is repeated many times throughout the ritual, and notes that it was impossible to obtain a translation of this song, as it was a closely guarded secret even within the tribe. However, beyond these observations he makes no attempt to analyze the lyrics, composition, or instrumentation of the song, focusing instead on the visual spectacle of the bull-dance, which he describes as being “of an exceedingly grotesque and amusing character”.

Catlin mentions that large water-filled sacks were used as drums, along with rattles, to accompany a song which is repeated many times throughout the ritual, and notes that it was impossible to obtain a translation of this song, as it was a closely guarded secret even within the tribe. However, beyond these observations he makes no attempt to analyze the lyrics, composition, or instrumentation of the song, focusing instead on the visual spectacle of the bull-dance, which he describes as being “of an exceedingly grotesque and amusing character”.