Poster advertising the World’s Columbian Exposition, hosted in Chicago, IL in 1893

As the pinnacle of culture and phenomena, the World’s Fair serves as a global platform for innovation and cultural exchange, showcasing the latest advancements and celebrating the diverse traditions of nations worldwide. At the turn of the 20th century, the World’s Fair was hosted in Chicago, Illinois in 1893 as the World’s Columbian Exposition, from May 1st to October 30th. While the World’s Fair is a place to display the world’s accomplishments, there are also instances where criticisms and suggestions hog the spotlight. Enter “American Music At The Fair: Mr. Stanton’s Suggestions As To Concerts And Operas–Education And Art”.

This primary source was found in a magazine article entitled “The Musical Visitor”, whose primary purpose was to report on music literature and news during the latter part of the 19th century. In this article, the author is not listed, however, the interviewee is the more appealing topic of discussion. Edmund C. Stanton was the Secretary and Managing Director of the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City, New York from 1884 to 1891. Throughout his career, Stanton was well-known in the music and operatic circles for bringing notable European artists (such as Lilly Lehman, Max Alvary, and Ivan Fischer) to sing for American audiences, as well as taking risks and introducing French, Italian, and German operas to New York “surpassed by none [other than Stanton] in the world”. Through his efforts, Stanton contributed significantly to the American opera scene through his administrative and musical influence.

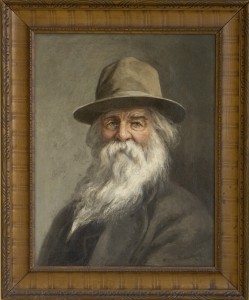

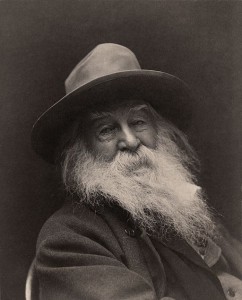

Edmund C. Stanton, Managing Director & Secretary of The Metropolitan Opera House, New York, NY (from 1884-1891).

At the time the article was written, Stanton had been “appointed to represent the amusement interests on the World’s Fair committee”, where he spoke with a reporter and shared his opinions on what the exhibition ought to “accomplish”. Included in the article are multiple quotations from Stanton:

“I think that the fair ought to be made to show to Europeans what America has accomplished in education, in music, and in art… [But] I think that American composers and American musicians ought to have such a chance to show the world what they can do as they have never had before.”

“I would suggest a large concert hall on the grounds of the fair, where daily concerts should be given. Of course, they would not be confined to the works of Americans, but most of them are naturalized or are likely to be, and they could represent the music of the country. There might be orchestral concerts and vocal and choral concerts, and I would not leave out the military bands such as Gilmore’s, Cappa’s, and others. I think they do a great deal to popularize good music.”

AMERICAN MUSIC AT THE FAIR.: MR. STANTON’S SUGGESTIONS AS TO CONCERTS AND OPERAS–EDUCATION AND ART.

In the readings on Monday by Thompson and Shadle, European influence in American music has often overshadowed the development of a distinct identity of American music. Stanton’s suggestions further enforce the idea that “white music traditions” (concert halls, military bands, etc) should be recognized and celebrated on the world’s stage. Therefore, European influence in American music is a defining hallmark of the general public’s understanding of “American” music, omitting the rich diversity of sounds and traditions that come from non-white groups.

WORKS CITED

“AMERICAN MUSIC AT THE FAIR.: MR. STANTON’S SUGGESTIONS AS TO CONCERTS AND OPERAS–EDUCATION AND ART.” The Musical Visitor, a Magazine of Musical Literature and Music (1883-1897), vol. 18, no. 11, 11, 1889, pp. 287. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/magazines/american-music-at-fair/docview/137493784/se-2.

“EDMUND C. STANTON DEAD: One Time Managing Director of the Metropolitan Opera House Company Passes Away in England.” The New York Times, The New York Times, timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1901/01/22/101177358.html?pageNumber=9.

“Libguides: World’s Fair Collection: Chronological List by Decades.” Chronological List by Decades – World’s Fair Collection – LibGuides at California State University Fresno, Fresno State Library, guides.library.fresnostate.edu/c.php?g=289187&p=1928035.

“The Metropolitan Opera Archives .” Metropolitan Opera Archives, The Metropolitan Opera, archives.metopera.org/MetOperaSearch/search.jsp?q=%22Edmund+C.+Stanton%22&src=browser&sort=PDATE.