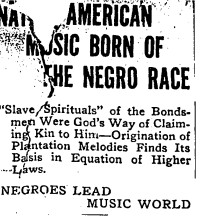

The Chicago Defender is a black-owned newspaper editorial founded in 1905 by Robert S. Abbott. Among articles, obituaries, comics, general supposed happenings of editorials at that time, the newspaper has . It was the first newspaper of its kind to include a health section, a full page of comics and have a circulation of over 100,000. It still runs today, though now it refers to itself as an exclusively online publication. Researching this publication’s monumental works, I found an article that very much applies to the ongoing discussion regarding “American Music’s” definition. In writing an editorial for this particular day, this unnamed author addresses an article written in the World-Herald, stationed in Omaha, Nebraska, and sets the record straight, more or less, centered from a black perspective.

The article in question makes large scale claims about African American contribution to the canon of America music at the time, asserting the popular adage that slave spirituals were no more than reworked tunes from white slave owners. While the author of the Defender’s article was cordial in their approach to responding to this notion(the author maintains that the Herald’s author “did the best he could”), this article centers black voices as being the instrumental factor in the creation of this music. Not only is it fundamentally pro-black in sentiment, the article is mostly full of name-dropped pieces and composers who are due credit.

He goes on to say the “slave spirituals” in question are the “only native American music”, which gave this amateur researcher a shock in his reading, as I am currently researching the works of Frances Densmore and her quest to document the music of the “American Indian”. Granted, this article uses the term “Native American” to describe the origins of music post colonization, but to my modern ear that segment struck me.

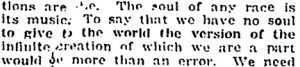

“The soul of any race is its music”

Articles like this, in long running publications of this nature, point me toward the problem of underrepresented voices in the world of music research. If we can’t reach out to people whom we make blanket statements about, or productively delve into the history and circumstances surrounding their music, what good is the research we are doing? I hope to do some further digging to find the specific author of this article, as the lack of such information is troubling when its contents seem so personal upon reading.

AMERICAN MUSIC BORN OF THE NEGRO RACE: “Slave Spirituals” of the … The Chicago Defender (Big Weekend Edition) (1905-1966); Jan 1, 1916; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Defender