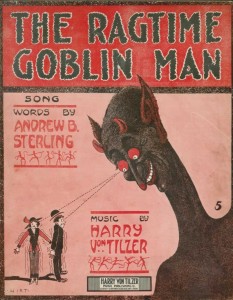

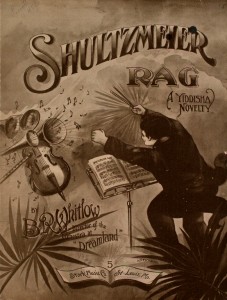

Last week we analyzed some shocking images in the form of sheet music. Printed, sold, and studied sheet music. I was not only floored by the experience of handling such egregious materials containing such ugly content. I was further surprised by the knowledge that “Hello my Baby”, a song sung to me as a child by my mother and the television alike, a song that just earlier that week I referenced in jest, was a minstrel song. The knowledge that minstrelsy is ever present in our present lives is equal parts haunting and infuriating, as with that knowledge comes the inevitable inward analysis required to recognize my place in perpetuating it. This week I decided to the sheet music that spoke to me the most, and go further and analyze those who created this work. Who would make this? Who would sell this? What other egregious and ugly content have they gotten away with making and selling? In doing so, I found the name. T.B Harms & Co. Publishing House.

B. Harms & Co were one of the most notable music distributors in the early 20th century. Founded in 1875 by Alex and Thomas Harms, the distribution company worked to produce music for many notable artists at the time, namely George Gershwin and Cole Porter, among others. In using the Sheet music Consortium to find scores released at the time, I found more striking pieces using racist imagery, writing and art.

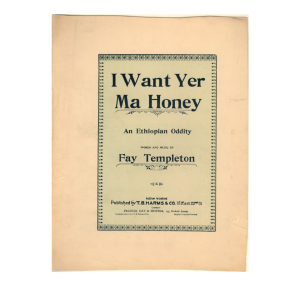

Take this for example. This piece, titled “I Want Yer Ma Honey”, is another example of a popular song, similar to “Hello Ma Baby”. The singer sings about waiting an unnamed figure badly, being passionately in love with them, though the text reads as follows:

“When de banjo’s a-strummin’

And de darkies’ a-hummin’

Den I want yer, ma honey

Yes I do”

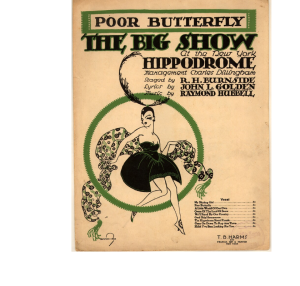

Another example shows that the racism and fetishization present in work from T.B. Harms was not exclusive to the black community. An example found from the SMC, titled “Poor Butterfly”, depicts a pulp story of an American soldier sailing to show a waiting Japanese Damsel how to “live and love the American way”, only to leave her stranded where she was found, waiting for her American hero to return.

These images can be painful to sift through and analyze, but the study of these images and scores not only clues us in to how large this issue was at the time, but also how ingrained this music and its ideals is in our everyday lives. These publishing dates are not that far from our present date, and these musicians weren’t necessarily nobodies. Their tunes remain, their influence lingers, and most importantly, the scars they’ve inflicted aren’t yet healed.

SMC Portal to T.B. Harms’ works: https://repository.duke.edu/dc/hasm?f%5Bpublisher_facet_sim%5D%5B%5D=T.B.+Harms%2C+New+York+%28N.Y.%29

Info on T.B. Harms & Co. : https://biblio.uottawa.ca/omeka1/silentfilmmusiccanada/exhibits/show/warner-chappell-music/t–b–harms—francis–day—hsheet musi