In class, we compared different recordings Scott Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag,” both from piano rolls played by the composer himself and from other musician’s renditions of the song. I thought this was an interesting exercise, especially getting to hear the music performed by the composer. Scott Joplin performed other songs on piano rolls as well, one of which was “Magnetic Rag.”

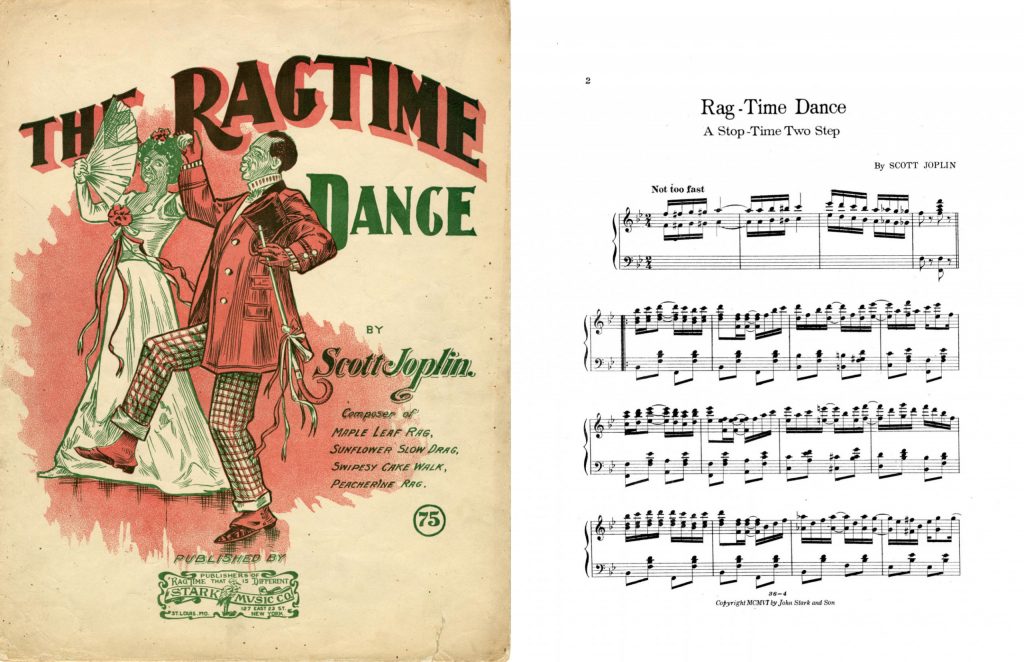

As you listen, follow along with this copy of sheet music from 1922.

Some things that I wanted to listen for were swung rhythms, articulation, and other stylistic touches that are not represented in the sheet music. The recording from the piano roll does not have swung rhythms per se, but the syncopation does give the music a distinctly swung feel. Something I noticed right away was the change in tempo in the few lines that can be heard on the piano roll but are not indicated in the sheet music. The first four measures are slower, and the section that begins at the first repeat is basically double the speed. Additionally, in the fourth measure, the rests shown in the sheet music cannot be heard in the piano roll.

When the first section after the intro is repeated, the piano roll deviates from the sheet music. Specifically, the right hand is an octave up. This technique is used again in subsequent sections. Throughout the piece, the repeated sections are shorter than in the sheet music. Generally, the performed version has more embellishments than the sheet music (which I suppose is somewhat common). However, I do notice that there is no arranger mentioned on the sheet music, which is often the case today when a new version of a song is published. Overall, there are not many instructions to the performer such as dynamics and articulations, however I’m not sure if that would have been typical of sheet music published at this time.

This sheet music is from 1922, while Scott Joplin made the piano rolls in 1916. The song “Magnetic Rag” was composed in 1914, so there is a significant amount of time between the creation of the piano roll and the publishing of the sheet music. Importantly, Joplin sadly died the year after the piano rolls were taken, and unless this is a reprint of other sheet music, he would not have seen this version. I think this is example is an interesting look at the variable aspect of this music, and it makes me wonder again about the issue of “authenticity” in music… it is useful to consider which version of the music is “more authentic.” I think it is very possible that Joplin has performed this piece differently at different times, and I would be interested to see the original version that Joplin wrote and how it compares to subsequent publishings.

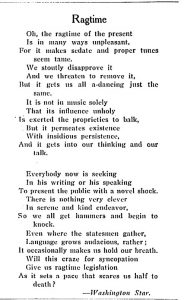

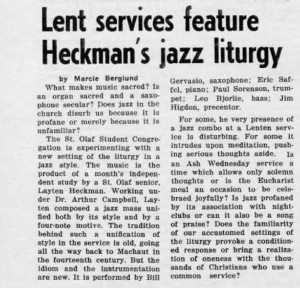

It seems St. Olaf has been hesitant to embrace Jazz as a sound musical genre, especially in regard to liturgical music. In this 1968 article of the Manitou Messenger, Ms. Berglund summarized a student jazz liturgy setting performed in chapel and asks questions that point to Jazz as a potentially profane and intrusive art form for worship. “Is jazz profaned by its association with night-clubs or can it also be a song of praise?”[1]

It seems St. Olaf has been hesitant to embrace Jazz as a sound musical genre, especially in regard to liturgical music. In this 1968 article of the Manitou Messenger, Ms. Berglund summarized a student jazz liturgy setting performed in chapel and asks questions that point to Jazz as a potentially profane and intrusive art form for worship. “Is jazz profaned by its association with night-clubs or can it also be a song of praise?”[1]