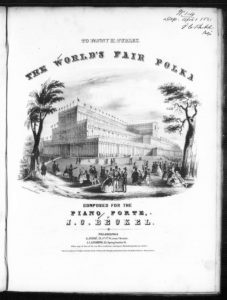

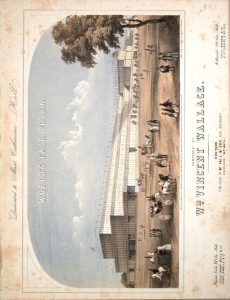

When seeing anything from the World’s Fair, isn’t your first thought “Yeah, I bet there’s a polka about this”. I’m kidding, of course. No one thinks that. However, you may be surprised to learn of the phenomenon that is the World’s Fair Polka, as there are at least two of them. One that I could find was written by J.C. Beckel and the other by W. Vincent Wallace, and they both were written during the time of the 1851 World’s Fair.

Why polka? Well, it was actually a very popular form of music in the United States during that time and J.C. Beckel, being an American himself, would have been hearing a lot of that music during the time. W. Vincent Wallace was Irish, but polka had also gained a lot of popularity in Europe.

There is not a whole ton of scholarship on the likely reasons why polka music might have been these two composer’s choice of genre to write about the world’s fair, but it is quite an interesting thing to think about. I would wonder if these two ever knew each other or knew of each other’s similar compositions. I would wonder about the kind of venues these would be performed at. Would they have been performed at the World’s Fair?

While there are always many questions to be asked and not as many answers to be found, I will leave you with this- isn’t it so interesting that musical genres and ideas can line up in incredibly interesting ways like this? It really makes a person think about all of the connections humans make all the time, sometimes without even knowing it.

Works Referenced:

Beckel, J. C. The World’s Fair polka. Philadelphia: T. C. Andrews, 1851. Notated Music. https://www.loc.gov/item/2023804129/.

“Beckel, James Cox 20.Dec.1811-2.Feb.1905 USA Pennsylvania, Philadelphia – Philadelphia Organist, Studied with Filippo Traetta and at the American Conservatory of Music Philadelphia, 1824-1832 Organist of St James Episcopal Church in Lancaster Pennsylvania ccm :: Beckel, James Cox Beckel. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://composers-classical-music.com/b/BeckelJamesCox.htm.

The rebellious, scandalous origins of polka – JSTOR daily. Accessed October 23, 2024. https://daily.jstor.org/the-rebellious-scandalous-origins-of-polka/.

Wallace, W. Vincent. The World’s Fair polka. New York: William Hall and Son, 1851. Notated Music. https://www.loc.gov/item/2023804034/.

“William Vincent Wallace.” Contemporary Music Centre, October 14, 2024. https://www.cmc.ie/composers/william-vincent-wallace.