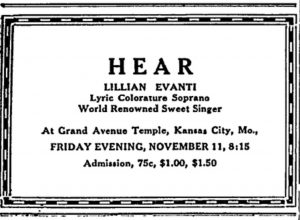

Lillian Evanti was a highly successful coloratura soprano in the 1920s-40s, performing and educating all over the country and abroad. Her success was charted in newspapers in many states, taking the form of advertisements, reviews, documentation of her appearances at dinner parties, book clubs, and other events, as well as other bits of news. One such advertisement appeared in the Plaindealer from Topeka, Kansas, on November 11, 1927.

Newspaper advertisement for her upcoming recital.

“Advertisement.” Plaindealer (Topeka, Kansas) TWENTY NINTH YEAR, no. FORTY FIVE, November 11, 1927: FOUR. Readex: African American Newspapers.

The blurb advertises a concert that evening in Kansas City, Missouri, and includes details of the time, place, and ticket pricing. Not only is this advertisement an interesting look into the culture of classical performing arts in the 1920s (imagine going to see a recital for 75 cents!), but it shows us that the history of American music is right in our communities. My hometown is only 30 minutes from Topeka, and an hour away from Kansas City. It is incredibly exciting to discover that your community plays a part in musical history, especially about an underrepresented artist that I never knew existed until we started our projects.

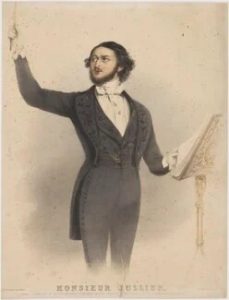

Portrait of Lillian Evanti.

From this article: Forlaw, Blair. “Opera Diva Lillian Evanti.” DC History Center, March 24, 2021. https://dchistory.org/opera-diva-lillian-evanti/. Sourced from the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.

But this begs the question– why had I never heard about Lillian Evanti before this project? Could it be that there is simply too much history to be discovered and Evanti’s career and legacy have not risen to the top of the reading list yet? Could it be that as a Black woman she gets swept under the rug to make more space for white artists? A common term to describe artists of color is “underrepresented,” because they are precisely that. There is significantly less documentation and evidence of the careers and achievements of BIPOC artists, musicians, composers, poets, etc, which is an unfortunate effect of the legacy of racism and discrimination that was so prevalent in the past and still ingrained in the system today.

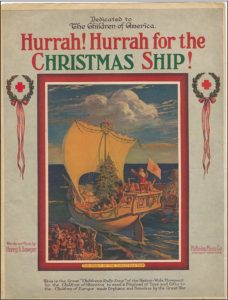

Lillian Evanti in costume for Verdi’s La Traviata.

Emilio Sommariva, Lillian Evanti wears opera costume from La Traviata, circa 1924-1935, Evans-Tibbs collection, Anacostia Community Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Box 1, Folder 3.

Perhaps the reason I never knew about Evanti is because we have been blatantly ignoring her and the other fantastic black women in music of the era in favor of white, European composers. We have a history of pushing away those that do not come from our communities. But the thing is– these artists are in our communities! I just proved that with a source from 30 minutes West of my hometown! Even though, sadly, there is less evidence of these amazing artists’ careers, it still exists! Especially in today’s age of online and digital databases and research possibilities, American musical history is right at our fingertips. The history of BIPOC artists is within our reach, we might just have to look a bit harder.

(Citations included in photo captions)