TW: blackface, racist language, minstrelsy, violence, misogyny

To any sane, sensible, and empathetic person alive today, minstrelsy is one of the great failures and shames of American history. The degrading songs and performances are deeply uncomfortable and disturbing to listen to, watch, or relive, and the lasting impacts (known, unknown, or purposefully ignored) continue to cause harm today.1 But we still study this phenomenon, whether in caution of reliving the past or perhaps to work toward bringing power back to those robbed of it.

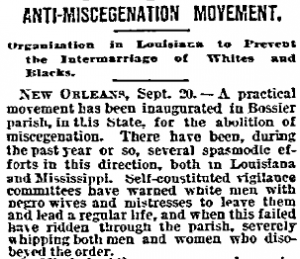

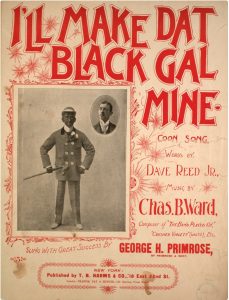

Sheet music cover for “I’ll Make Dat Black Gal Mine,” featuring a portrait of George H. Primrose in blackface.

Charles B. Ward, I’ll make dat black gal mine. (New York, New York: T.B. Harms & Co., 78 East 22nd St., 1896). https://levysheetmusic.mse.jhu.edu/performance/72601

In its heyday, the worst of minstrel songs actively contributed to the formation of racist and sexist ideals of white Americans toward Black Americans. “I’ll make dat black gal mine,” written by Charles B. Ward and recorded in 1921 by Harry C. Browne2, is an example of the worst. With incredibly racist, sexist, and generally problematic lyrics by David Reed, and an almost satirical melody and accompaniment, this song perpetuates harmful stereotypes and shows blatant disrespect for black people. The song’s main theme features a wildly ambitious speaker who will do everything in his power to “win dat gal,” despite the protests of her father. Not only is the gal in question, Caroline, treated as property and some kind of prize to win, but the speaker will even resort to violent, racially-charged murder in order to “steal away” Caroline. The casual threats of murder and violence, the constant use of slurs, and the disregard for female autonomy (not to mention a white performer in blackface) all characterize black people as sub-human and undeserving of respect, contributing to the harmful racist rhetoric ever-prevalent in minstrelsy.

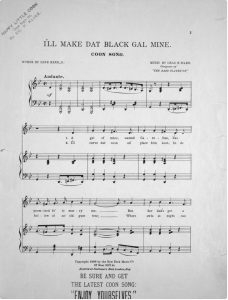

The music itself supports the mockery and comedic ridicule by providing a cartoonish, threatening and creeping accompaniment in a sort of “oom-pah” style. The recording provided by the Library of Congress3 (originally published by Columbia records) features a vocalist with banjo (both performed by Harry C. Browne) accompanied by an orchestra. Browne sings with a heavy baritone sound, prominent vibrato, and tall vowels, plucking his banjo with an almost comedic twang and liveliness.

The first page of music, showcasing its accompaniment style and disrespectful lyrics.

Charles B. Ward, I’ll make dat black gal mine. (New York, New York: T.B. Harms & Co., 78 East 22nd St., 1896). https://levysheetmusic.mse.jhu.edu/performance/72601

White men like Charles B. Ward, David Reed, and Harry C. Browne writing and performing this awful song is not only harmful to the black people it mocks, threatens, and disrespects, but also to its white audiences, because it condones the same attitude and behavior from them. It is bad enough that a song this horrible was theorized, composed, and recorded, but then perhaps it became popular, which is even worse. Once it is popular, white listeners are subject to the song’s message, which tells them it is okay to treat black people as objects. Presenting these harmful images creates a never ending cycle of internalized and institutionalized racism and misogyny, which unfortunately has not left our culture yet. One can only hope that education has brought more awareness to the disgrace that was/is minstrelsy, and that folks today recognize how cruel and inhumane this genre continues to be to Black Americans.

1 See this amazing article from NPR about lasting effects of minstrelsy and uncomfortable truths: Theodore R. Johnson, III, “Recall That Ice Cream Truck Song? We Have Unpleasant News For You,” Code Switch: Word Watch, National Public Radio, May 11, 2014, https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2014/05/11/310708342/recall-that-ice-cream-truck-song-we-have-unpleasant-news-for-you.