There are certain musical genres that are considered to be inherently American, and one often overlooked one is musical theater. While the musical is a broad concept, the first modern musical is usually attributed to The Black Crook, which opened in New York in 1866.1 Therefore, America was at the heart of the beginnings of the musical, many would say. But is that the case?

As is common with history, giving a topic a second glance usually sheds new light and much more meaning is discovered. This is also the case with musicals, as a quick search will bring up information related to the first musicals in New York City. David Armstrong, a musical theater ‘legend’ who teaches at the University of Washington, talks about how “musical theater got its start following a huge wave of Irish immigration in the late 1800s.”2 So musical theater is some form that could be thought of as Irish. But aren’t Irish in America considered Americans? This is where debating the origin of a particular genre gets muddled, and complexities are often shown with a simplistic cover.

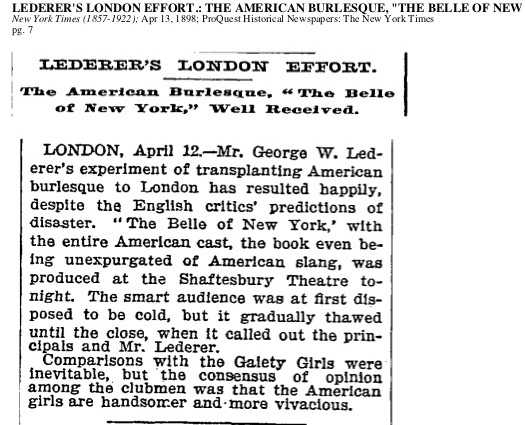

One particular musical named “Belle of New York” has an interesting story. While it was successful in the US, British audiences (London, in particular) enjoyed this musical as well. A picture of this musical from 1898 is shown below.3

Compared to a mere 64 performances in New York (perhaps ironically), the “Belle of New York” ran “for an almost unprecedented 674 performances” in Britain.4 An 1898 New York Times newspaper describes this fact as an “experiment of transplanting American burlesque to London”.5 While typically thought of as distinct regions, the British Isles and the US become tightly interrelated by musical theater. While Irish immigrants in New York were possibly large influencers and founders of musical theater, this musical art eventually found its way back to the British Isles, especially London. Because the majority of Americans are immigrants, it makes sense that this type of American music is essentially the music of immigrants. Musical theater, especially in its early days, is an especially good example of this multi-regional origin and spread.

1 Stewart, James. “Timeline: American Musicals.” 13 February 2017. Vermont Public. https://www.vermontpublic.org/programs/2017-02-13/timeline-american-musicals

2 “The Surprising History of Musical Theater.” University of Washington. https://www.washington.edu/storycentral/story/the-surprising-history-of-musical-theater/

3 Byron Company, Plays, “The Belle of New York.” 1898. Museum of the City of New York.

4 “The Belle of New York [Musical Comedy].” Josef Lebovic Gallery. https://www.joseflebovicgallery.com/pages/books/CL200-5/the-belle-of-new-york-musical-comedy

5 Lederer’s London Effort, The New York Times. 12 April 1898. https://www.proquest.com/hnpnewyorktimes/docview/95619956/CC62D1F7E093472EPQ/4?accountid=351