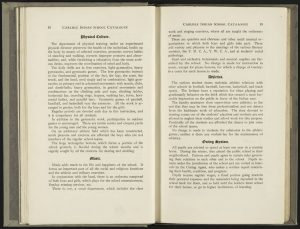

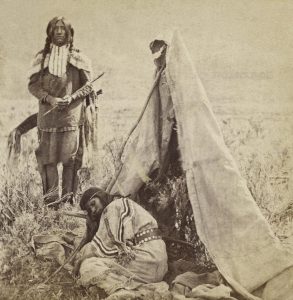

The 1915 “Tentative Course of Study for United States Indian Schools” opens with the line “Indian schools must train the Indian youth of both sexes to take upon themselves the duties and responsibilities of citizenship.” (1915, BIA) This benign sentence tells us little of the real rationale for indian schools and how they were ran across the country.

Kill the Indian, Save the Man

In 1892 at the National Conference of Charities and Correction in Denver, Colorado, Richard Pratt gave a speech titled “The Advantages of Mingling Indians with Whites.” This massively influential speech lays out his idea for native assimilation. Pratt is vehemently against the reservation system and the forcing of native people out of their land. Unfortunately, this is not out of respect for their right to self determination but instead the forceful assimilation of native people into white, capitalist culture.

“A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one… In a sense. I agree with the sentiment ,but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”1

But Beethoven, Really?

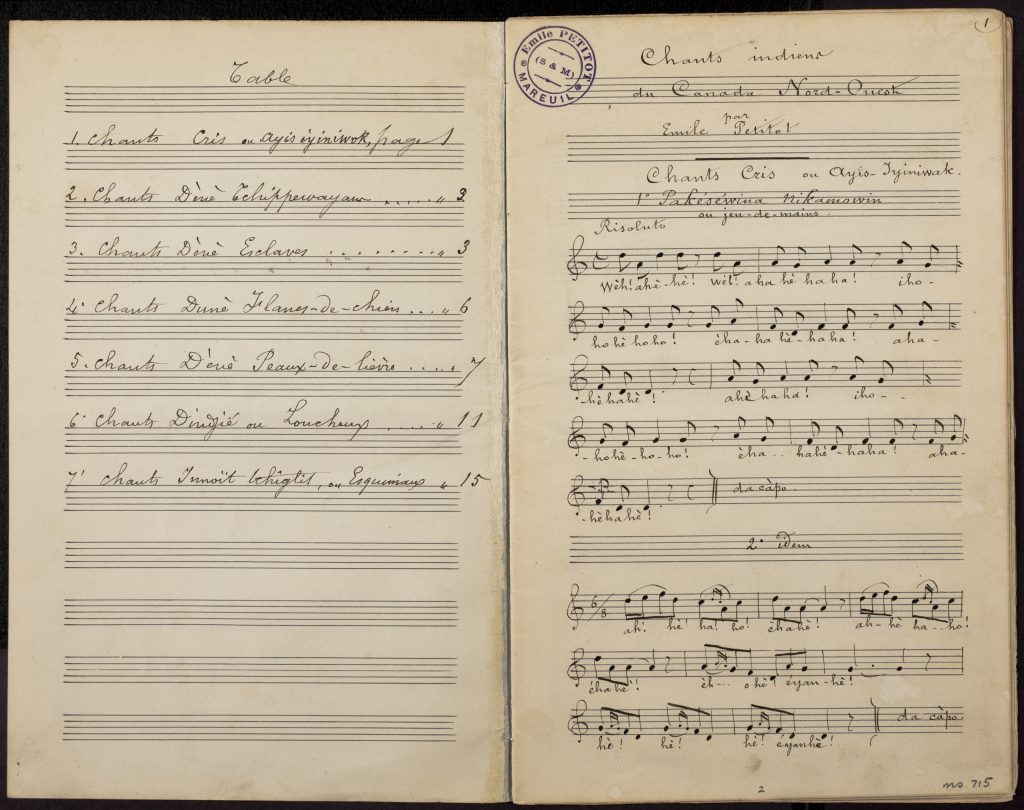

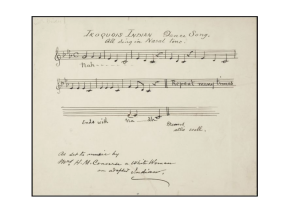

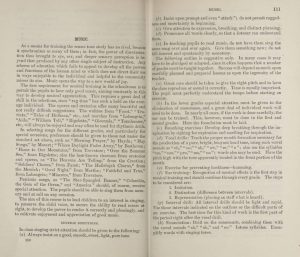

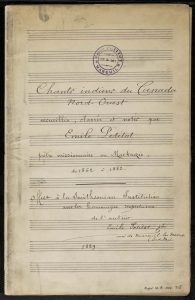

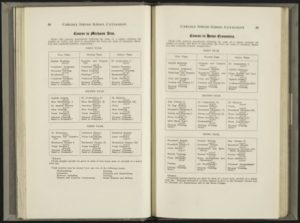

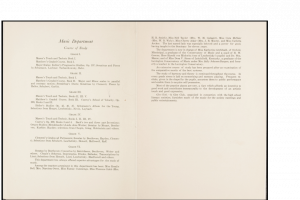

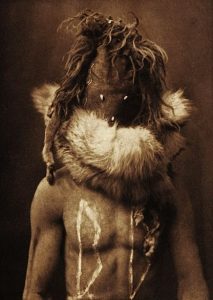

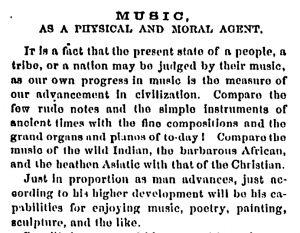

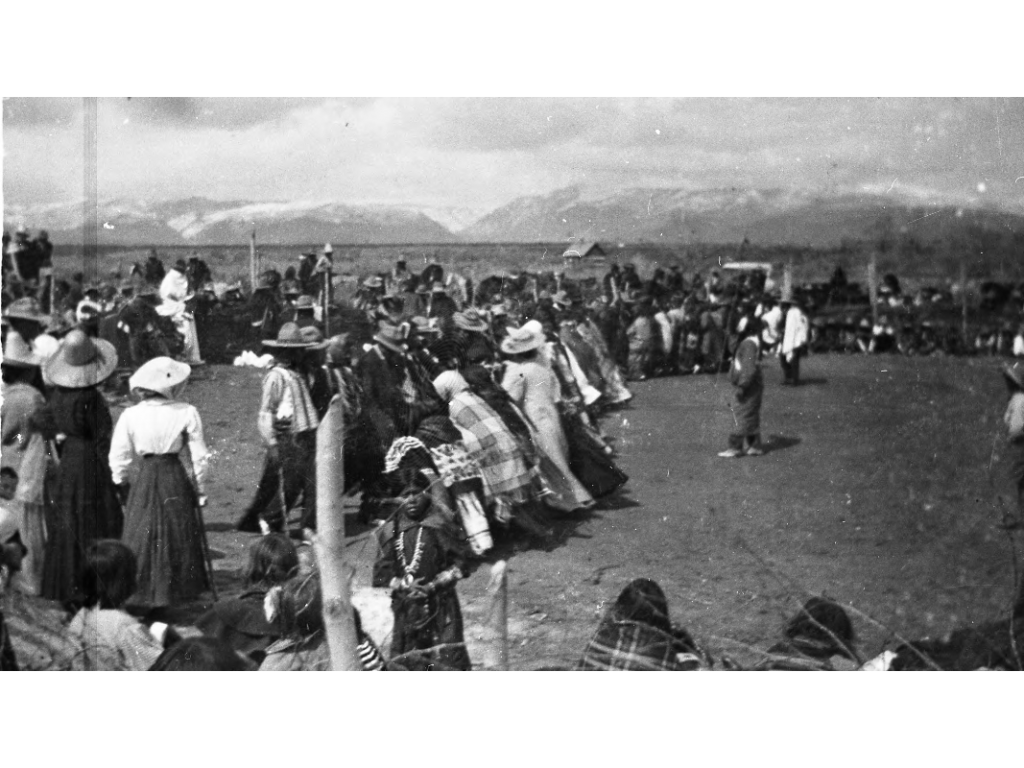

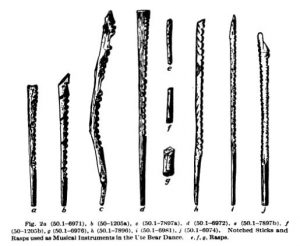

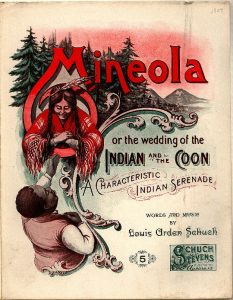

Yes, Really. Western musical education was a critical strategy in the cultural genocide that was the goal of these schools. The course of study states that the goal of music education is to “preserve the child voice” and to “cultivate enjoyment and appreciation of good music.2” These are the words used to launder the dirty reality of these schools. Children were abducted from their homes and put in these schools to learn solfege and listen to Beethoven. If Pratt had his way they would never learn the music of their cultural heritage, let alone be allowed to perform it.

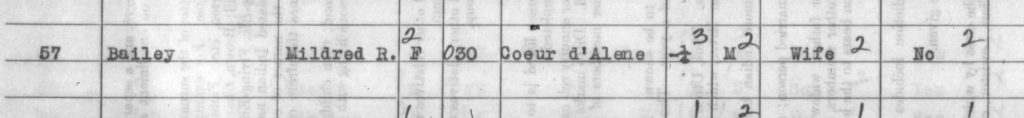

There were sixteen American Indian boarding schools in Minnesota alone. The first of which opened in 1871 and many were ran through the 1970s. That is nearly a century of similar music education being taught in these boarding schools and in the classes of Saint Olaf College. That education which so many of us have a love/hate relationship with was used to tear down native culture across the country and close to home.

Further Reading on Boarding Schools in Minnesota

https://www.mnopedia.org/native-american-boarding-schools

(“The Advantages of Mingling Indians with Rights”: R. H. Pratt on the Education of Native Americans | Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center).

Sells, Cato. Tentative Course of Study for United States Indian Schools. Prepared under the Direction of Commissioner of Indian Affairs. 1915. Government Printing Office, https://www.indigenoushistoriesandcultures.amdigital.co.uk/Documents/Detail/tentative-course-of-study-for-united-states-indian-schools.-prepared-under-the-direction-of-commissioner-of-indian-affairs./7023327?item=7023390. Indigenous Histories and Cultures.