Concurrent Resolution No. 49 was filed by the Coeur d’Alene tribe of Idaho in the Idaho House of Representatives in March 2012 with the goal of correcting historical records and reuniting Mildred Bailey1, one of the first female vocalists in jazz history. “I think it’s not known at all. Hardly nobody knew,” says Coeur d’Alene Tribal Chairman Chief Allan. “Not only being Native, but being a woman in that era, to be so strong and keep pushing and not to give up, that would help a lot of our young tribal members who are looking for a role model,” says Chief Allan2.

For background on the Coeur d’Alene tribe, we can find a large monetary exchange between the tribe and the United States government. As a result of the constant stream of settlers into the area, the Coeur d’Alene people effectively transitioned from traditional means of nomadic survival in just fifty years after first making contact with Europeans and adopted static agriculture3. The Coeur d’Alene tribe paid the United States government half a million dollars in 1889 to give up the northern portion of their ancestral lands, as stated in the Indian Commissions Agreement. All Coeur d’Alene families received an equal share of the funds, most of which went into purchasing cutting-edge farming machinery4. Mildred Bailey, who was born in 1900 and was nurtured by her Coeur d’Alene mother and a Scotch/Irish father on a farm next to the reservation, portrayed this fast changing environment3.

For over eight decades, Bailey, a member of the Coeur d’Alene tribe, was mostly recognized as a “white jazz singer.” Conversations concerning the origins of jazz rarely addressed Bailey’s Indian identity; it stayed in the farmlands of Coeur d’Alene, where she learned to move, speak, and sing like a neglected crop. In a 1930s America that was still divided along racial lines, Bailey could easily be pardoned if she decided to conceal her Native American heritage, but she never made the attempt to do so3. On the contrary, she was happy to share it with everyone around her as a source of pride. The reason Mildred Bailey was labeled as “white” was that the jazz narrative she was a part of could not accommodate Indian jazz players. The faulty label of “white jazz-singer” was important for a number of reasons, not the least of which was Bailey’s significant influence on the jazz and pop scenes. Bailey invented the vocal “swing” style that many singers attempted to imitate, including “Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, Bing Crosby, and Tony Bennett.” (Hamill 33) Bailey chose to attribute her voice sixty years after it was recorded for the final time, to the Indian music of her childhood rather than her contemporaries.3

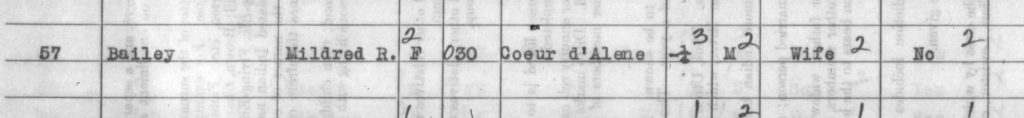

1“Page 260 Us, Indian Census Rolls, 1885-1940.” Fold3, www.fold3.com/image/216137757. Accessed 25 Oct. 2023.

2Robinson, Jessica. “Tribe Seeks to Correct Jazz History on Native Singer’s Heritage.” NPR, NPR, 15 Mar. 2012, www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=148715100.

3 Berglund, Jeff, Johnson, Jan, and Lee, Kimberli, eds. Indigenous Pop : Native American Music from Jazz to Hip Hop. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2016. Accessed October 26, 2023. ProQuest Ebook Central.

4 Dinwoodie, David. “Landscape Traveled by Coyote and Crane: The World of the Schitsu’Umsh (Coeur d’Alene Indians).” Montana; the Magazine of Western History 53, no. 1 (Spring, 2003): 75. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/landscape-traveled-coyote-crane-world-schitsuumsh/docview/217955660/se-2.