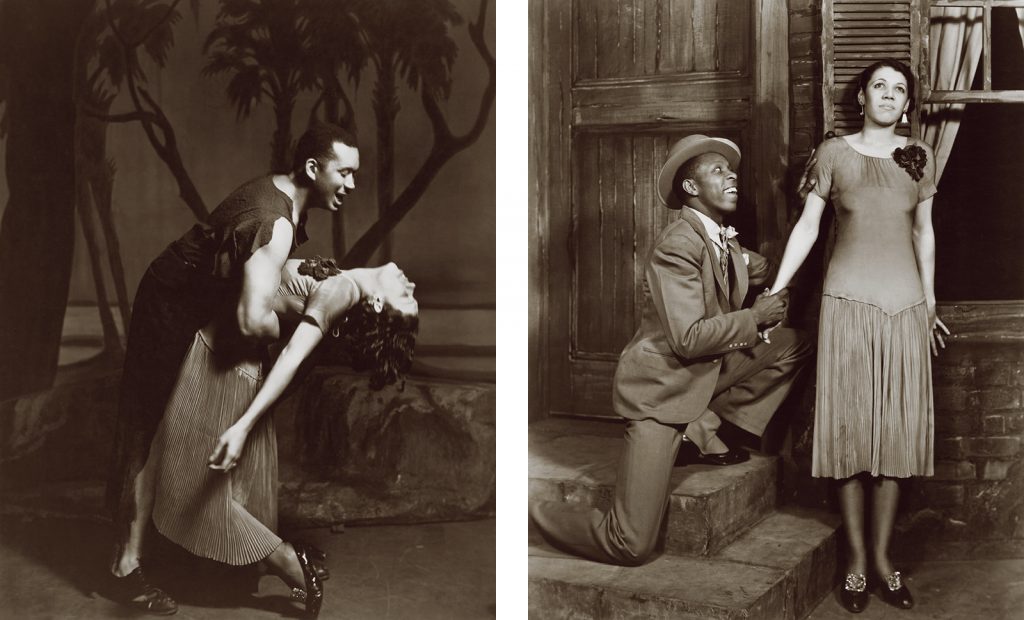

Arguably the most famous American musical theater production of the 20th century is Porgy and Bess, “an American Folk Opera,” the peak of Gershwin’s career. There is rarely a night in the world when Porgy and Bess isn’t performed live on stage. The distinct characters of the songs have spawned hundreds of arrangements. in Maurice Peress’s book “Dvorák to Duke Ellington: A Conductor Explores America’s Music and Its African American Roots”, We are able to see the intersections between “Porgy and Bess”, Gershwin, and the African-American identity. 1

Arguably the most famous American musical theater production of the 20th century is Porgy and Bess, “an American Folk Opera,” the peak of Gershwin’s career. There is rarely a night in the world when Porgy and Bess isn’t performed live on stage. The distinct characters of the songs have spawned hundreds of arrangements. in Maurice Peress’s book “Dvorák to Duke Ellington: A Conductor Explores America’s Music and Its African American Roots”, We are able to see the intersections between “Porgy and Bess”, Gershwin, and the African-American identity. 1

Although “Porgy and Bess” was a cultural gift, it is not exempted from some controversy. “Combining the sons of Russian Jewish immigrants, George and Ira Gershwin, with the scion of a prominent white South Carolina family, DuBose Heyward, and his wife Dorothy, an Ohio native, to depict an exclusively African-American story”(Cooper 2019)—is this an example of good melting-pot American art? Is it improper cultural appropriation? The fact that the most well-known opera depicting the African-American experience was produced by a team made up exclusively of white people is no secret to Black composers looking for acceptance. 2

In a 1936 essay for Opportunity, an Urban League journal, Hall Johnson, a black composer, arranger, and choir director whose Broadway hit musical “Run, Little Chillun!” had been successful, said Gershwin was “as free to write about Negroes in his own way as any other composer to write about anything else.” However, he noted that the finished product was “Gershwin’s idea of what a Negro opera should be, not a Negro opera by Gershwin.” Decades later, the writer James Baldwin reiterated this criticism in a review of the movie, saying that although he enjoyed “Porgy and Bess,” it was still “a white man’s vision of Negro life.”2

“Porgy and Bess” provided jobs for black singers with classical training during a time when discrimination kept them from appearing at the Met and other prestigious venues. When the initial tour of the play arrived to the segregated National Theater in Washington, DC, the black stars of the show took a stance and promised not to perform. The theater was compelled to integrate as a result, albeit only briefly. “Porgy” established the careers of other black vocalists , such as Leontyne Price, who sang the part of Bess right out of Juilliard.2

Eventually, It began featuring American culture internationally. However, this came with some problems. “Porgy and Bess”, being a Jewish composer’s work about African Americans, the work’s European premiere in Copenhagen during World War II sparked controversy because of its staging, which was seen as a direct protest against the Nazi regime. During the middle of the Cold War, in the mid-1950s, author Truman Capote wrote an entertaining portrayal of the inherent ironies of this visit of Leningrad and Moscow.2 The piece seemed to be fitting into the operatic canon, proving the pieces power.