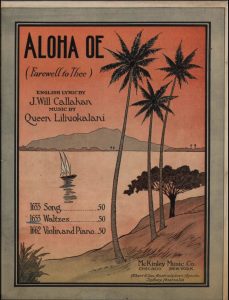

Hawaii is internationally regarded as a paradise and is the perfect place for exotic getaways in the heart of the Pacific Ocean. But until 1778, it was a hierarchical, sovereign nation populated by indigenous Native Hawaiians who were self-sufficient and coexisted peacefully with their families, their islands, and their culture. Since foreigners began to settle on the Hawaiian islands, the native Hawaiian population and culture have fought to survive from their near extinction.1Specifically for this blog post, Native Hawaiian music was significantly impacted by the 19th-century immigration of Europeans and Americans. It is said that “by the late nineteenth century, Hawaiians could hear popular music from other countries in ports and cities that handled the growing trade” (Hearingtheamericas.org) after Christian hymns were introduced by missionaries.2 Hawaii’s government was taken over by US-based companies in the 1890s, and soon after that the island was annexed by the US as a colonial property. By this time, Hawaiian musicians had established a style that would have a significant impact on popular music all around the world.2 For example, the song “Aloha ‘Oe,” is revered as a symbol of traditional Hawaiian culture. Queen Lili’uokalani, the last monarch of the Hawaiian Islands, composed it more than a century ago. The song has both subtle and explicit themes about power hierarchies because it was written and recorded at a period of political and cultural unrest in Hawai’i. Although the song was originally written in 1878 as a mele ho’oipoipo (love song) between a man and a woman, Native Hawaiians through time adapted it socially, politically, and culturally into a song of melancholy farewell between the Queen and her country.3 Since its creation, “Aloha ‘Oe” has grown to be among the most well-known and well-known Hawaiian melodies. Following the overthrow of the Hawaiian kingdom in 1893 and Hawaii’s unlawful designation as the 50th US state, demand for the song’s sheet music and performances surged significantly.3 In the figure at the top of the page, you can see one of the many adaptions of this native song. We can even see that they changed the lyrics to english.4 Hawaiian music took the music world by storm, turning their into a genre and “culture” that every American has “taken apart of”.

1 Osorio, Emma Kauana. 2023. “Struggle for Hawaiian Cultural Survival – Ballard Brief.” Ballard Brief, July. https://ballardbrief.byu.edu/issue-briefs/struggle-for-hawaiian-cultural-survival.

2 “Hearing the Americas · Hawaiian Music · Hearing the Americas.” n.d. https://hearingtheamericas.org/s/the-americas/page/hawaiian-music.

3 T. Chow, Evelyn. 2018. “The Sovereign Nation of Hawai’i: Resistance in the Legacy of ‘Aloha ‘Oe.’” SUURJ: Seattle University Undergraduate Research Journal. https://scholarworks.seattleu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1020&context=suurj#:~:text=Lili%27uokalani%20initially%20wrote%20“Aloha,Maunawili%20Ranch%20(Imada%2035).

4 Historic Sheet Music Collection, University of Oregon. “Aloha oe” Oregon Digital. Accessed 2023-10-12. https://oregondigital.org/concern/documents/00000002j