Myths. They’re nasty. They slow research. Given that my group for the final project is researching T.O.B.A., the Theater Owners Booking Association, which booked the performances for many notable Black vaudeville performers, let’s dispel some myths surrounding T.O.B.A. so they do not get in the way of our research.

Myth No. 1: T.O.B.A. was founded by Sherman H. Dudley.

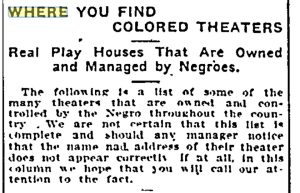

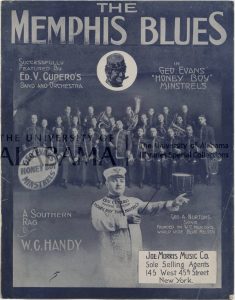

T.O.B.A. was actually founded in 1909 by brothers Fred and Anselmo Barrasso, theater owners in Memphis who wanted to create a theater chain for Black performers1. In this Freeman (a Black newspaper) article2 you can see Fred’s name listed for the theater he managed, the Savoy Theatre, under the heading “Where You Find Colored Theaters: Real Play Houses That Are Owned And Managed By Negroes”.

But wait a second… Fred Barrasso wasn’t Black. He was an Italian immigrant. Stephen Huff, professor of Theatre and Dance at the University of Southern Florida, explains in the journal article, “The Impresarios of Beale Street: African American and Italian American Theatre Managers in Memphis, 1900–1915”,

“It may be that this is an example of the ambivalent racial status of Italian immigrants during this period. Accepted as “white” in some circles, perhaps they were, at the same time, accepted as nonwhite by the African Americans they worked with and served in the business of black entertainment.”3

Myth No. 2: The T.O.B.A. Circuit Was Also Known As The Dudley Circuit

Nope! Two separate things. Dudley’s Theatrical Circuit began in 1891, while Sherman H. Dudley was still performing. In 1912, 3 years after Fred and Anselmo Barrasso founded T.O.B.A., Sherman H. Dudley bought theaters, and stopped performing in 1913 to focus on the circuit. In 1916, the Dudley Circuit was absorbed into the Southern Consolidated Circuit, which got into many arguments with T.O.B.A.4

Here’s a mapping project for the Dudley Circuit (by Maeve Nagel-Frazel)!

Myth No. 3: So the T.O.B.A. Circuit Began in 1909….

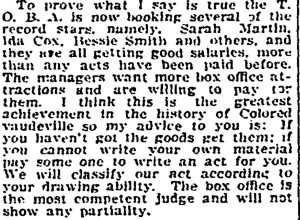

In 1921, the Southern Consolidated Circuit (the rival circuit) was absorbed into T.O.B.A., allowing the circuits to combine about 100 theaters5. This new, larger T.O.B.A. is the T.O.B.A. that would be advertised in Black newspapers, become popular, and develop quite the circuit, booking major vaudeville stars. The success and fame of T.O.B.A. was due to Sherman H. Dudley, who was not only an effective businessman but a beloved figure, colloquially known as Uncle Dud and even starting a newspaper series in The Chicago Defender called “Dud’s Dope”. In one of the first articles, Dudley talks about wanting to bring big names to T.O.B.A. and his success in bringing Sarah Martin, Ida Cox, and Bessie Smith to T.O.B.A.6, dispelling another myth that T.O.B.A. is what helped give performers their starts. While sometimes true, T.O.B.A. also sought after performers that already had acclaim.

Conclusion

Determining the myths surrounding T.O.B.A. helped me answer previously unanswered questions about our group project. For example, for some of our data points, our group was unsure if the performances were through T.O.B.A. or not. Any unsure data points of performances before 1921, I would argue, are not through the T.O.B.A. Circuit. The bulk of advertising and booking announcements are found through Black newspapers, and that advertisement was the work of Sherman H. Dudley.

I also realized through this post that misinformation surrounding T.O.B.A. is rampant, even in works that I considered to be well-researched. This just goes to show how much more research needs to be done. What myths do you want dispelled?

Footnotes

1 Robinson, Cedric J. Forgeries of Memory and Meaning : Blacks and the Regimes of Race in American Theater and Film before World War II Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

2 “Where You Find Colored Theaters. Real Play Houses That Are Owned and Managed by Negroes.” Freeman (Indianapolis, Indiana) XXIII, no. 21, May 21, 1910: 6. Readex: African American Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&docref=image/v2%3A12B28495A8DAB1C8%40EANAAA-12C4FA7BF3D1D2C8%402418813-12C4FA7C56786930%405-12C4FA7DA97933E8%40Where%2BYou%2BFind%2BColored%2BTheaters.%2BReal%2BPlay%2BHouses%2BThat%2BAre%2BOwned%2Band%2BManaged%2Bby%2BNegroes.

3 Huff, Stephen. “The Impresarios of Beale Street: African American and Italian American Theatre Managers in Memphis, 1900–1915.” Theatre Survey 55, no. 1 (2014): 22–47. doi:10.1017/S0040557413000525.

4 Knight, Athelia. “He Paved the Way for T. O. B. A.” The Black Perspective in Music 15, no. 2 (1987): 153–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/1214675.

5 George-Graves, Nadine. “Spreading the Sand: Understanding the Economic and Creative Impetus for the Black Vaudeville Industry.” Continuum Journal, https://continuumjournal.org/index.php/spreading-the-sand.

6 Dudley, S. H. “DUD’S DOPE.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Feb 16, 1924. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/duds-dope/docview/492010353/se-2?accountid=351.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/silhouette-of-five-players-in-jazz-band--white-background-808891-005-59fcba5a4e4f7d001a6818a3.jpg)