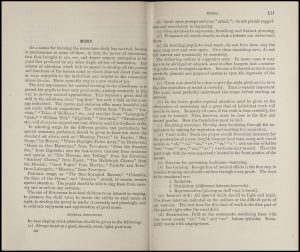

Ellington wins Spingarn award. Article published in the Daily Defender.1

Duke Ellington is commonly known as one of the most influential and important voices in creating American music in the 20th century. His influence on “classical music, popular music, and, of course, jazz, simply cannot be overstated.”2 Ellington moved to New York in 1923, and by1927 Ellington’s band was hired to play at the Cotton Club and stayed for five years.3 By as early as 1930, Ellington and his band were famous and he was beginning to be recognized as a serious composer.3

Ellington reached the height of his career in the 1930s and 1940s. After World War II, demand for big-band music dwindled. Ellington, along with many other artists, struggled during this time, although he continued to compose and perform.4 In 1956, “with a triumphant performance at the Newport Jazz Festival, Ellington re-emerged as an important voice in contemporary music.”5 Following this success, Ellington began to perform and record albums with others such as John Coltrane, Max Roach and Charles Mingus, and Coleman Hawkins.

The article above explains the Spingarn award that Ellington won in 1959. This award is given to African American people who “stimulate the ambition of colored youth.”6 Ellington won this award for his outstanding contributions to American music over many years. It is commonly known as a “gold medal” for “the highest or noblest achievement by an American Negro during the preceding year or years,” and is one of the most coveted awards in its field. Along with this award, Ellington also “had been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters, awarded a doctor of music degree from Yale University, given the Medal of Freedom” following his death in 1974 due to lung cancer.

Bibliography

Cofresi, Diana. “Duke Ellington ~ Duke Ellington Biography.” PBS, March 3, 2023. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/duke-ellington-about-duke-ellington/586/.

“Duke Ellington.” Duke Ellington | Songwriters Hall of Fame. Accessed November 8, 2023. https://www.songhall.org/profile/Duke_Ellington.

“Duke Ellington Wins Spingarn Award: Select Duke Ellington for ’59 Spingarn Award.” 1959.Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1956-1960), Jun 23, 1. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/duke-ellington-wins-spingarn-award/docview/493738881/se-2.

Footnotes

1 “Duke Ellington Wins Spingarn Award: Select Duke Ellington for ’59 Spingarn Award.” 1959.Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1956-1960), Jun 23, 1. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/duke-ellington-wins-spingarn-award/docview/493738881/se-2.

2 “Duke Ellington,” Duke Ellington | Songwriters Hall of Fame, accessed November 8, 2023, https://www.songhall.org/profile/Duke_Ellington.

3 “Duke Ellington,” Duke Ellington | Songwriters Hall of Fame, accessed November 8, 2023, https://www.songhall.org/profile/Duke_Ellington.

4 Diana Cofresi, “Duke Ellington ~ Duke Ellington Biography,” PBS, March 3, 2023, https://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/duke-ellington-about-duke-ellington/586/.

5 Diana Cofresi, “Duke Ellington ~ Duke Ellington Biography,” PBS, March 3, 2023, https://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/duke-ellington-about-duke-ellington/586/.

6 Diana Cofresi, “Duke Ellington ~ Duke Ellington Biography,” PBS, March 3, 2023, https://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/duke-ellington-about-duke-ellington/586/.