Barak Obama, Donald Trump, and Hillary Clinton have all used popular songs to further their presidential campaigns in recent years, but this idea is surprisingly not new to American politics.

When I began researching for my final paper, which is about presidential campaign songs, I wanted to gain a broad understanding of these songs and their usage, so I headed to Google. The first song that came up is “I Like Ike.” “I Like Ike” was used for Dwight D. Eisenhower’s presidential campaign in 1952. I wanted to take a closer look at this primary source for my blog post this week because this trend of using a pop song for a campaign song seems to have sprung up from “I Like Ike.”

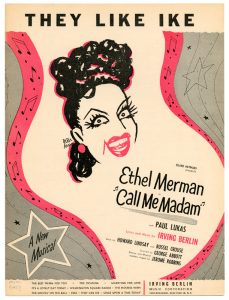

“I Like Ike” was written by Tin Pan Alley songwriter Irving Berlin in 1950. It was published and performed under the title “They Like Ike,” first appearing in Berlin’s musical, Call Me Madam. The musical is centered around a Washington D.C. socialite-turned-ambassador. The show was a major hit and won a Tony Award for best score. At the time, Eisenhower was not running for the presidency, but Berlin was hopeful that he would.

Once Eisenhower announced his candidacy, Berlin switched the lyrics around a bit and changed the title to “I Like Ike.” The song became a cornerstone for the Eisenhower campaign strategy, as the phrase “I Like Ike” was widespread on advertisements, posters, buttons, and even license plates. With the change of a few words, Berlin’s Broadway hit became a driving force in winning Eisenhower’s presidency.

The song has elements that make for a solid campaign song: a march-like accompaniment and a simple to follow melody line. If I was to take away the lyrics from the sheet music, you or I probably couldn’t tell this song apart from any other written in the lineage of Tin Pan Alley.

After Eisenhower won the presidency, Berlin continued in his role as musical fanboy for Eisenhower, as he would later update the song two more times to “I Still Like Ike,” “Ike for Four More Years,” and “We Still Like Ike.”

P.S. Unfortunately, all versions of “I Like Ike” are still under copyright, so we’re not able to view and compare them, except for the original publication of the campaign song that I was able to attain through The Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection.

Primary Sources:

Berlin, Irving. I Like Ike. New York, New York: Irving Berlin Music Corporation, 1952.

Berlin, Irving. They Like Ike. New York, New York: Irving Berlin Music Corporation, 1950.

Secondary Source:

“Irving Berlin ‘They Like Ike’ from Call Me Madam.” Yale University Library: Exhibits at the Irving S. Gilmore Music Library: Hail to the Chief: Irving Berlin, “They Like Ike” from Call Me Madam, 2010, www.library.yale.edu/musiclib/exhibits/hail_chief/like_ike.html. Accessed 11 November, 2019.