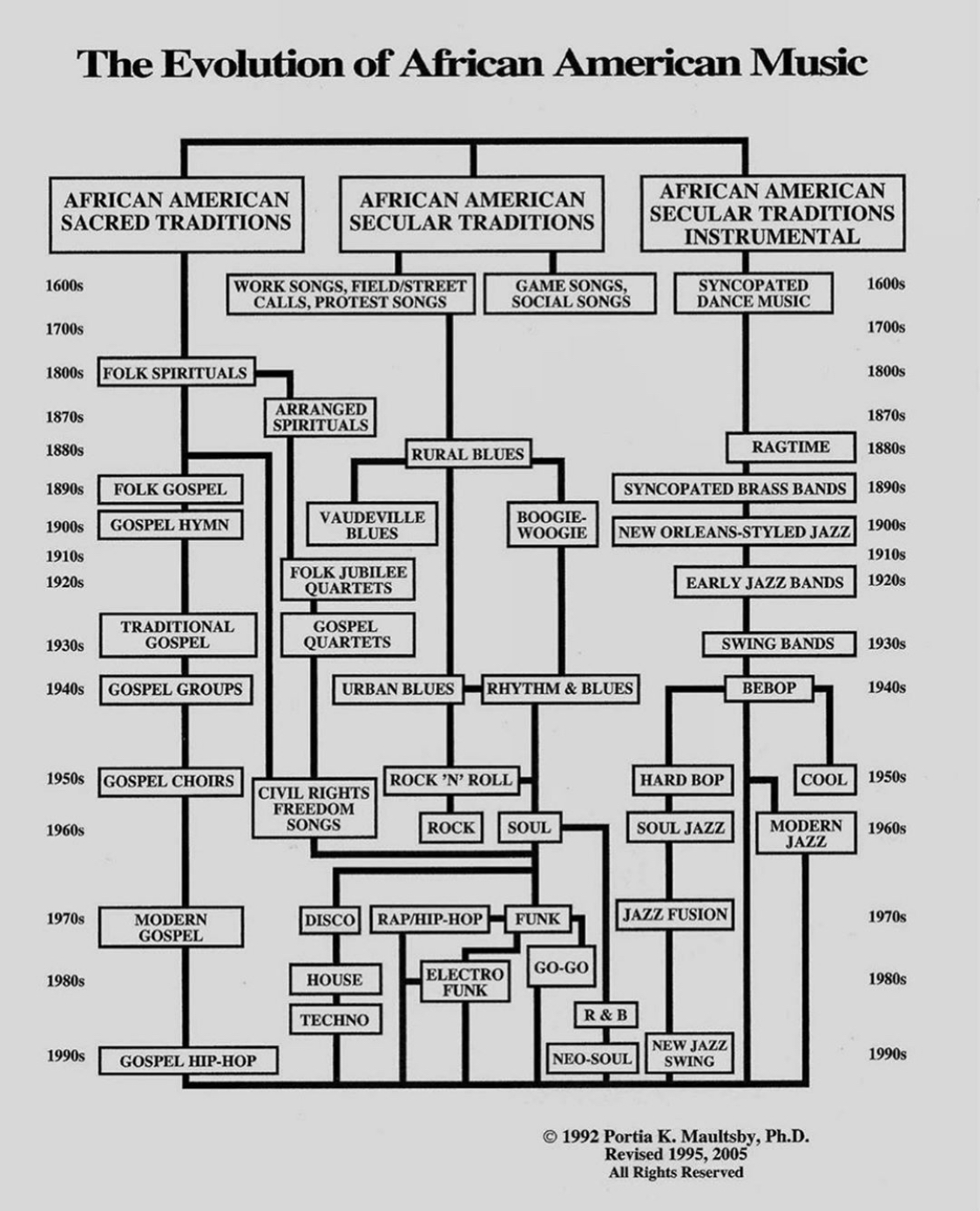

In the late 1950s a turn was happening among the American populous. Suddenly, Jazz was starting to catch on as popular music and was recognized as one of the true, if not THE truest form of American music. However, it wasn’t just in America where Jazz was getting recognition. In 1958, the Chicago Defender1 released an article detailing a Soviet author’s opinion on American Jazz as “not so bad”. The author certainly made their opinions on how Jazz serves the bourgeoise and ultimately hurts the proletariate as a result, there was praise and more importantly in my opinion, recognition, of the early roots of Jazz being stemmed in folk music traditions.

The Soviet author then goes on to explain that there is almost no popular music in the USSR- and that they wish they could create a sense of national identity within their musical culture. This notion comes specifically from this author not even two decades on since Shostakovich wrote his Symphony no. 5 which is shrouded in mystery as to its origins and message. What we do know about this symphony is that it was the saving hail-mary for Shostakovich’s career- and he was already being pressured by the Soviet government to begin planting the seeds of a national musical identity.

Shostakovich in the late 1950s.

This contrasts heavily against American popular music’s development because of the former’s rather natural progression by the people with little government involvement. This progression, however, took almost 200 years to lead to Jazz. The Soviet government wanted this progression to happen faster, they were in an arms race, space race, and even… a music race concerning culture against the Americans. Did Soviet music ever take off? In the classical- surely as modern Russian composers have a clear place in the instrumental canon, but it seems that only today due to the internet and streaming services is Russian popular music finding its footing within its own Eastern European roots.

https://www.proquest.com/hnpchicagodefender/docview/493699491/CA623B654A3F41B8PQ/4?accountid=351