Leonard Bernstein’s life and dreams of music direction were supported by his talent, utter extroversion, and thoughtfulness. Bernstein however faced three points of potential controversy against himself, being a Jewish-American homosexual. While Bernstein couldn’t hide his Jewish-American heritage in a widely European and at times anti-semitic music scene, he did certainly try to hide his homosexuality. Bernstein didn’t want anything getting in the way of him and his dreams of musical direction, not even himself. And so, Bernstein went onto marry Felicia Montealegre on September 9, 19513, despite having relations to varying degrees with other composers of the time from Ned Rorem to Aaron Copland2. On the topic of his sexuality, known by his wife, she wrote thus:

“First: we are not committed to a life sentence — nothing is really irrevocable, not even marriage (though I used to think so).

Second: you are a homosexual and may never change — you don’t admit to the possibility of a double life, but if your peace of mind, your health, your whole nervous system depend on a certain sexual pattern what can you do?

Third: I am willing to accept you as you are, without being a martyr or sacrificing myself on the L.B. altar.”1

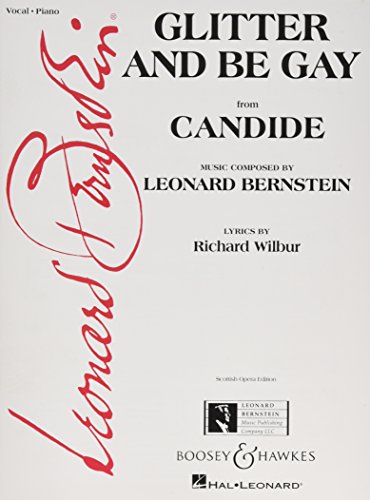

Bernstein makes less discrete nods to his sexuality in his compositions. Junior from A Quiet Place (1983) is engaged in a same-sex relationship with Francois, as is Maximillian with several partners in Candide (1956).

Bernstein’s “Glitter And Be Gay” from Candide

Bernstein, although shaded in many respects, made the first few modern attempts at incorporating the LGBTQ’s voice into music. As a member of the LGBTQ community, I am grateful that I feel I can express myself freely in the musical culture I am surrounded in- and part of that is because of the path that Bernstein paved. Since Bernstein we have had LGBTQ conductors and composers such as Pauline Oliveros, Marin Alsop, and Yannick Nézet-Séguin. It is not an understatement to stay that in the modern culture of classical music Bernstein has solidified a place in the academy for openly LGBTQ musicians in spite of his reserved legacy concerning his sexuality.

Bernstein, Leonard. Leonard Bernstein Letters. Yale University Press, 2014.