American idealism and the ever-changing concept of the “American Dream” seem to be well accompanied by the arts. The idea of setting music or text to American fantasies-which typically involve gaining large amounts of wealth, owning a huge plot of land, and/or embracing patriotism- is typically enjoyed by those that the American Dream has been realized within or sold to as an idea.

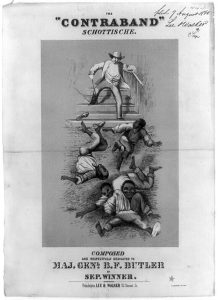

In the post-Civil War reconstruction era United States, the American Dream was changing alongside the rapid industrialization of the country. People were getting richer faster, and a drab new landscape of factories and mills replaced expansive picturesque farms. The American Dream of creating wealth off of plantations (and subsequently slaves) was shifting towards making money off of factory labor and its exports. This was changing how music accompanied the idea of the American Dream during the late 1800s.

4 /> Steamboats at a Nashville Dock in 1863

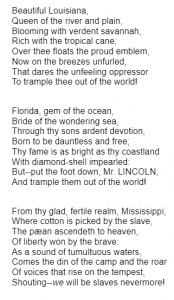

The simultaneous need to hold onto the musical trends and racial injustices of yesteryear turned many musicians sour to a new wave of music that continued selling American idealism. Boston Conservatory music scholar and lecturer Dr. Louis Elson stated in periodical The Christian Observer as part of an interview in 1898 that “I am a firm believer that American Music is just Southern Music. I have often said that the reason “Dixie” is the most characteristic outcome of the War is because you can’t set a calico factory or flour mill to music, but that Southern plantation life is characteristic and poetic…”2

Elson then goes on to name Dvorak’s New World Symphony2 expressing his hope that someone will provide an equivalent for Southern music- reinforcing his belief that Southern music is true American music- and that the slave economy is easier to romanticize than an industrial economy. This is laughable considering Dvorak’s New World Symphony

was based heavily off of themes of immigration, diversity,3

and shared culture- the antithesis of the kind of music Elson advocates for while simultaneously calling Native American the music of “savages”.

The redefining of American music has happened several times over, but a pattern has certainly emerged. American music favors diversity, adaptation (following the nature of American music itself), and justice. As diversity, justice, and social consciousness evolve as principles in America, so too will American music, and the American dream that accompanies that music.

http://www.classicalmusictoday.net/blog/new-world-symphony-manuscript-comes-to-the-new-world

https://www.proquest.com/americanperiodicals/docview/136125214/F1B647EEFC6D4BADPQ/24?accountid=351